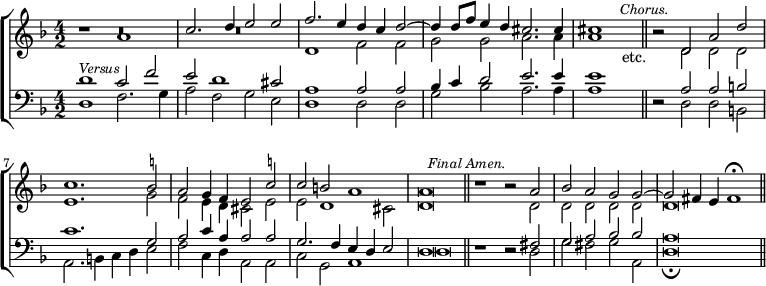

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Though Byrd survived the 16th century by more than 20 years, he was not the last great Master who cultivated the true Polyphonic style in England. It was practised, with success, by men who were young when he was old, yet who did not all survive him. We see a very enchanting phase of it, in the few works of Richard Farrant which have been preserved to us. His style is, in every essential particular, Venetian; and so closely resembles that of Giovanni Croce, that one might well imagine the two Masters to have studied together. Farrant is best known by some 'Services,' and three lovely Anthems, the authenticity of one of which—'Lord, for Thy tender mercies' sake'—has lately been questioned, we think on very insufficient grounds, and certainly in defiance of the internal evidence afforded by the character of its Harmonies. Besides these, very few of Farrant's works are known to be in existence. The Organ Part of a Verse-Anthem—'When as we sate in Babylon'—is preserved in the Library at Christ Church; together with two Madrigals, or, rather, one Madrigal in two parts—'Ah! Ah! alas,' and 'You salt sea gods'; but such treasures are exceedingly rare.

Farrant died in 1580, three years before the birth of Orlando Gibbons, with whom the School finished gloriously in 1625. By no Composer was the dignity of English Cathedral Music more nobly maintained than by this true Polyphonist; who adhered to the good old rules, while other writers were striving only to exceed each other in the boldness of their licences. He took licences also. No really great Master was ever afraid of them. Josquin wrote Consecutive Fifths. Palestrina is known to have proceeded from an Imperfect to a Perfect Concord, by Similar Motion, in Two-part Counterpoint. Luca Marenzio has written whole chains of Ligatures, which, if reduced to Plain Counterpoint, in accordance with the stern test demanded by Fux, would produce a dozen Consecutive Fifths in succession. Orlando Gibbons has claimed no less freedom, in these matters, than his predecessors. In the 'Sanctus' of his 'Service in F,' he wrote, between bars 4 and 5, the most deliberate Fifths that ever broke the rule. But he has never degraded the pure Polyphonic style by the admixture of foreign elements incompatible with its inmost essence. He had the good taste to feel what the later Italian Polyphonists never did feel, and never could be made to understand—that the oil of the old system could never, by any possibility, be persuaded to combine with the wine of the new. Of the nauseous mixtures, compounded by Monteverde and the Prince of Venosa, we find no trace, in any one of his writings. Free to choose whichever style he pleased, he attached himself to that of the Old Masters, and conscientiously adhered to it, in spite of the temptations by which he was surrounded on every side. That he fully appreciated all that was good in the newer method is sufficiently proved by his Instrumental Music. His 'Fantasies of III Parts for Viols,' and his Pieces for the Virginals, in 'Parthenia,' are full of quaint fancy, and greatly in advance of the age. But in his Vocal Compositions, he was as true a Polyphonist as Tallis himself. Had he taken the opposite course, he would, no doubt, have been equally successful; for he would, most certainly, have been equally consistent. As it was, he not only did honour to the cause he espoused, but he established an incontestable claim to our regard as one of its brightest ornaments. His exquisitely melodious Anthem, for 4 Voices, 'Almighty and everlasting God,'