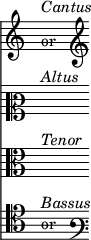

in the first instance: but it was always transcribed, for use, in separate Part-Books; and it was not until the 17th century was well advanced, that Vocal Scores became common, either in MS., or in print. When they did so, they were arranged very nearly as they are now, though with a different disposition of the Clefs, which were so combined as to indicate, within certain limits, the Mode in which the Composition was written; the presence or absence of a B♭, at the Signature, serving to distinguish the Chiavi naturali, or Modes at their natural pitch, from the Chiavette (or Chiavi trasportate), transposed a Fifth higher, or a Fourth lower.[1]

Natural Modes.

|

|

Transposed Modes.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

In the 18th century, the number of Clefs was more restricted; but, the C Clef was always retained for the Soprano, Alto, and Tenor Voices, except in the case of Songs intended for popular use.

At the present day, the Soprano Clef is seldom used, except in Full Scores of Vocal Music with Orchestral Accompaniments; though most Italian Singers are acquainted with it. In Scores for Voices alone, the Soprano, Alto, and Tenor Parts, are usually written in the G Clef, on the Second Line, with the understanding that the Tenor Part is to be sung an Octave lower than it is written. Sometimes, but less frequently, the same condition is attached to the Alto Part. Sometimes the Alto and Tenor Parts are written in their proper Clefs, and the Soprano in the G Clef; or the Soprano and Alto may both be written in the G Clef, and the Tenor in its proper Clef. All these methods are in constant use, both in England and on the Continent.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The doubled G Clef, in the third and fourth of the above examples, is used by the Bach Choir, to indicate that the part is to be sung in the Octave below.

II. The earliest examples of the Orchestral Score known to be still in existence are those of Baltazar de Beaujoyeaulx's 'Ballet comique de la Royne'[2] (Paris, 1582); Peri's 'Euridice' (Florence, 1600; Venice, 1608);[3] Emilio del Cavaliere's 'Rappresentazione dell' Anima e del Corpo'[4] (Rome, 1600); and Monteverde's 'Orfeo'[5] (Venice, 1609, 1613). A considerable portion of the Ballet is written, for Viols and other Instruments, in five Parts, and in the Treble, Soprano, Mezzo-Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass Clefs. In Cavaliere's Oratorio, and Peri's Opera, the Voices are accompanied, for the most part, by a simple Thorough-bass, rarely relieved even by an Instrumental Ritornello. Monteverde's 'Orfeo' is more comprehensive; and presents us, in the Overture, with the first known example of an obbligato Trumpet Part.

As the taste for Instrumental Music became more widely diffused, the utility of the Orchestral Score grew daily more apparent; and, by degrees, Composers learned to arrange its Staves upon a regular principle. The disposition of the Stringed Baud, at the beginning of the 18th century, was

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 474.

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 567b.

- ↑ Ib. pp. 534–535.

- ↑ Ib. p. 499a and b.

- ↑ Ib. pp. 500–501.