On the other hand, it is quite possible for a musical piece to follow the general course of a poem or story, and, if only by evoking similar states of mind to those induced by considering the story, to form a fitting musical commentary on it. Such programme pieces are Sterndale Bennett's 'Paradise and the Peri' overture, Von Bülow's 'Sänger's Fluch,' and Liszt's 'Mazeppa.' But as the extent to which composers have gone in illustrating their chosen subjects differs widely, as much as the 'Eroica' differs from the 'Battle Symphony,' so it will be well now to review the list of compositions—not a very bulky one before the present century—written with imitative or descriptive intention, and let each case rest on its own merits.

Becker, in his 'Hausmusik in Deutschland' mentions possessing a 16-part vocal canon 'on the approach of Summer,' by a Flemish composer of the end of the 15th century, in which the cuckoo's note is imitated, but given incorrectly. This incorrectness—D C instead of E♭ C—may perhaps be owing to the fact (discussed time ago in the 'Musical Times') that this bird alters her interval as summer goes on.[1] It is but natural that the cuckoo should have afforded the earliest as well as the most frequent subject for musical imitation, as hers is the only bird's note which is reducible to our scale, though attempts have been made, as will be further on, to copy some others. Another canonic part-song, written in 1540 by Lemlin, 'Der Gutzgauch auf dem Zaune sass,' Becker transcribes at length. Here two voices repeat the cuckoo's call alternately throughout the piece. He also quotes a part-song by Antonio Scandelli (Dresden, 1570) in which the cackling of a hen laying an egg is comically imitated thus: 'Ka, ka, ka, ka, ne-ey! Ka, ka, ka, ka, ne-ey!' More interesting than any of these is the 'Dixieme livre des chansons' (Antwerp, 1545) to be found in the British Museum, which contains 'La Bataille à Quatre de Clem. Jannequin' (with a 5th part added by Ph. Verdelot), 'Le chant des oyseaux' by N. Gombert, 'La chasse de lièvre,' anonymous, and another 'Chasse de lièvre' by Gombert. Two at least of these part-songs deserve detailed notice, having been recently performed in Paris. The first has been transcribed in score by Dr. Burney[2] in his 'Musical Extracts' (Add. MS. 11,588), and is a description of the battle of Marignan. Beginning in the usual contrapuntal madrigal style with the words 'Escoutez, tous gentilz Gallois, la victoire du noble roy Françoys,' at the words 'Sonney trompettes et clairons the voices imitate trumpet-calls thus,

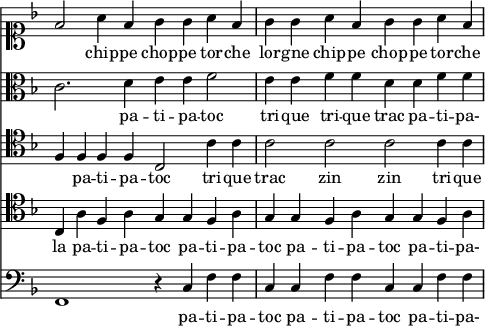

and the assault is described by a copious use of onomatopeias such as 'pon, pon, pon,' 'patipatoc,' and 'farirari,' mixed up with exclamations and war-cries. Two bars of quotation will perhaps convey some idea.

This kind of thing goes on with much spirit for a long while, ending at last with cries of 'Victoire au noble roy François! Escampe toutte frelon bigot!' Jannequin is said to have written some other descriptive pieces, in the list of which the 'Chant des oyseaux' of Gombert is wrongly included. [See Jannequin.] [App. p.751 "The sentence on p. 35b, l. 4–7 after musical example, is to be omitted, since both Jannequin and Gombert wrote pieces with the title of 'Le Chant des Oyseaux.' The composition by the former is for four voices, and was published in 1551, that of Gombert being for three voices, and published in 1545."] This latter composition is chiefly interesting for the manner in which the articulation of the nightingale is imitated, the song being thus written down: 'Tar, tar, tar, tar, tar, fria, fria, tu tu tu, qui lara, qui lara, huit huit huit huit, oyti oyti, coqui coqui, la vechi la vechi, ti ti cū ti ti cū titi cū, quiby quiby, tu fouquet tu fouquet, trop coqu trop coqu,' etc. But it is a ludicrous idea to attempt an imitation of a bird by a part-song for Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass [App. p.751 "omit the words 'Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass,' since the composition referred to is in three parts, not four. It is 'in four parts' in the sense only of being in four sections, or movements], although some slight effort is made to follow the phrasing of the nightingale's song. The 'Chasse de lièvre' describes a hunt, but is not otherwise remarkable.

The old musicians do not display much originality in their choice of subjects, whether for imitation or otherwise. 'Mr. Bird's Battle' is the title of a piece for virginals contained in a MS. book of W. Byrd's in the Christ Church Library, Oxford. [App. p.751 "refer to Lesson, and Virginal Music, where the exact title is given."] The several movements are headed 'The soldiers' summons—the March of footmen—of horsemen—the Trumpets—the Irish march—the Bagpipe and Drum—etc.' and the piece is apparently unfinished. Mention may also be made of 'La Battaglia' by Francesco di Milano (about 1530) and another battlepiece by an anonymous Flemish composer a little later. Eckhard or Eccard (1589) is said to have described in music the hubbub of the Piazza San Marco at Venice, but details of this achievement are wanting. The beginning of the 17th century gives us an English 'Fantasia on the weather,' by John Mundy, professing to describe 'Faire Wether,' 'Lightning,' 'Thunder,' and 'A faire Day.' This is to be seen in 'Queen Elizabeth's Virginal Book.' The three subjects quoted overleaf alternate frequently, giving thirteen changes of weather, and the piece ends with a few bars expressing 'a cleare day.'

- ↑ Spohr, in his Autobiography, has quoted a cuckoo in Switzerland which gave the intermediate note—G. F, E.

- ↑ Reprinted in the Prince de la Moskowa's collection.