![{ \mark "31." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 2/4 \relative c'' {

\slashedGrace b8 c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "32." \grace { b16 c } c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "33." \grace { b16 c d } c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "34." c2\upprall \bar "||" \break \mark "35." b32 c d c d[ c d c] d c d c d[ c d c] \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/1/31zz948ynsnhvd97rskgjk655la5qrb/31zz948y.png)

From a composer's habit of writing the lower prefix with one, two, or three notes, his intentions respecting the commencement of the ordinary shake without prefix, as to whether it should begin with the principal or the subsidiary note, may generally be inferred. For since it would be incorrect to render Ex. 32 or 33 in the manner shown in Ex. 36, which involves the repetition of a note, and a consequent break of legato—it follows that a composer who chooses the form Ex. 32 to express the prefix intends the shake to begin with the upper note, while the use of Ex. 33 shows that a shake beginning with the principal note is generally intended.

![{ \mark "36." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 2/4 \relative b' { b32 c c d c[ d c d] c^"(Ex. 32.)" d c d c[ d c d] \bar "||" \break b16*2/3[ c d] d32 c d c d[^"(Ex. 33.)" c d c] d c d c } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/1/n176fddcqkyldozq0vlnq5nzwfo56vp/n176fddc.png)

That the form Ex. 31 always implies the shake beginning with the principal note is not so clear (although there is no doubt that it usually does so), for a prefix is possible which leaps from the lower to the upper subsidiary note. This exceptional form is frequently employed by Mozart, and is marked as in Ex. 37. It bears a close resemblance to the Double Appoggiatura. [See that word, vol. i. p. 79.]

Mozart, Sonata in F. Adagio.

Among modern composers, Chopin and Weber almost invariably write the prefix with two notes (Ex. 32); Beethoven uses two notes in his earlier works (see Op. 2, No. 2, Largo, bar 10), but afterwards generally one (see Op. 57).

The upper note of a shake is always the next degree of the scale above the principal note, and may therefore be either a tone or a semitone distant from it, according to its position in the scale. In the case of modulation, the shake must be made to agree with the new key, independently of the signature. Thus in the second bar of Ex. 38, the shake must be made with B♮ instead of B♭, the key having changed from C minor to C major. Sometimes such modulations are indicated by a small accidental placed close to the sign of the trill (Ex. 39).

Chopin, Ballade, Op. 67.

Beethoven, Choral Fantasia.

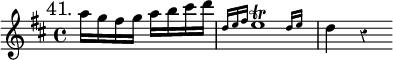

The lower subsidiary note, whether employed in the turn or as prefix, is usually a semitone distant from the principal note (Ex. 40), unless the next following written note is a whole tone below the principal note of the shake (Ex. 41). In this respect the shake follows the rules which govern the ordinary turn. [See Turn.]

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 10, No. 2.

Mozart, Rondo in D.

A series of shakes ascending or descending either diatonically or chromatically is called a Chain of Shakes (Ital. Catena di Trille; Ger. Trillerkette). Unless specially indicated, the last shake of the series is the only one which requires a turn. Where the chain ascends diatonically, as in the first bar of Ex. 42, each shake must be completed by an additional principal note at the end, but when it ascends by the chromatic alteration of a note, as from G♮ to G♯, or from A to A♯, in bar 2 of the example, the same subsidiary note serves for both principal notes, and the first of such a pair of shakes requires no extra principal note to complete it.

Beethoven, Concerto in E♭.

![{ \mark \markup \small \italic "Played." \key b \major \time 4/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative e'' {

e32 fis e fis e[ fis e fis] e fis e fis \tuplet 5/4 { e[ fis e fis e] } fis g fis g fis[ g fis g] fis g fis g \tuplet 5/4 { fis[ g fis g fis] } | g ais g ais g[ ais g ais] gis ais gis ais \tuplet 5/4 { gis[ ais gis ais gis] } s_"etc." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/x/nxhbebom9qf3jk3ht3vhkfxi81ig9km/nxhbebom.png)

In pianoforte music, a shake is frequently made to serve as accompaniment to a melody played by the same hand. When the melody lies near to the trill-note there need be no interruption to the trill, and either the principal or the subsidiary note (Hummel prescribes the former, Czerny the latter) is struck together with each note of the melody (Ex. 43). But when the melody lies out of reach, as is often the case, a single note of the shake is omitted each time a melody-note is struck (Ex. 44). In this case