closely studied. A great quality in the French language, as sung, is the fact that the amount of vocal sound is always at the same average. No sudden irruption of a mass of consonants, as in German or English, is to be feared. In vocal purity, though not in amount of vocal sound, German takes precedence of French, as containing more Italian vowel, but it is at times so encumbered with consonants that there is barely time to make the vowel heard. The modified vowels ü, ö and ä are a little troublesome. The most serious interruption to vocal sound is the articulation of ch followed by s, or worse still, of s by sch. But if the words are well chosen they flow very musically. The first line of Schubert's 'Ständchen Leise fliehen meine Lieder' is a good example; all the consonants being soft except the f. In contrast to this we have 'Flüsternd schlanke Wipfel rauschen' with thirty-one letters and only nine vowels. But perhaps the very worst phrase to be found set to music in any language, and set most unfortunately, occurs in the opera of 'Euryanthe.' In the aria for tenor, 'Wehen mir Lüfte Ruh,' the beautiful subject from the overture is introduced thus:

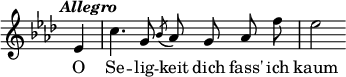

As this subject is to be executed rapidly the g and k are not easy to get in in time. Then come td; then ch and f together; then ss. A jump of a major 6th on the monosyllable ich with its close vowel and the transition from ch to k on the E♭ are a piling of Pelion on Ossa in the creation of difficulty, which could have been avoided by arranging the syllables so that the moving group of notes might be vocalised. And this passage is the more remarkable as coming from one who has written so much and so well for the voice; namely, Weber.

Polyglot English requires more careful analysis than any other language before it can be sung, on account of the nature of its vowel-sounds and the irregularity of its orthography, consequent upon its many derivations. Its alphabet is almost useless. There are fourteen different ways (perhaps more) of representing on paper the sound of the alphabetical vowel I. There are nine different ways of pronouncing the combination of letters ough. The sound of the English language is by no means as bad as it is made to appear. No nation in the civilised world speaks its language so abominably as the English. The Scotch, Irish and Welsh, in the matter of articulation, speak much better than we do. Familiar conversation is carried on in inarticulate smudges of sound which are allowed to pass current for something, as worn-out shillings are accepted as representatives of twelve pence. Not only are we, as a rule, inarticulate, but our tone-production is wretched, and when English people begin to study singing, they are astonished to find that they have never learned to speak. In singing, there is scarcely a letter of our language that has not its special defect or defects amongst nearly all amateurs, and, sad to say, amongst some artists. An Italian has but to open his mouth, and if he have a voice its passage from the larynx to the outer air is prepared by his language. We, on the contrary, have to study hard before we can arrive at the Italian's starting-point. Besides, we are as much troubled as Germans with masses of consonants. For example, 'She watched through the night,' 'The fresh streams ran by her.' Two passages from Shakespeare are examples of hard and soft words. The one is from King Lear, 'The crows and choughs that wing the midway air.' In these last five words the voice ceases but once, and that upon the hard consonant t. The other sounds are all vocal and liquid, and represent remarkably the floating and skimming of a bird through the air. The other is from Julius Cæsar, 'I'm glad that my weak words have struck but thus much fire from Brutus.' The four hard short monosyllables, all spelt with the same vowel, are very suggestive.

All these difficulties in the way of pronunciation can be greatly overcome by carefully analysing vowels and consonants; and voice production, that difficult and troublesome problem, will be in a great measure solved thereby, for it should be ever borne in mind by students of singing, as one of two golden precepts, that a pure vowel always brings with it a pure note—for the simple reason that the pure vowel only brings into play those parts of the organs of speech that are necessary for its formation, and the impure vowel is rendered so by a convulsive action of throat, tongue, lips, nose or palate.

In studying voice-production let three experiments be tried, (1) Take an ordinary tumbler and partially cover its mouth with a thin book. Set a tuning-fork in vibration and apply the flat side to the opening left by the book, altering the opening until the note of the fork is heard to increase considerably in volume. When the right-sized opening is found, the sound of the fork will be largely reinforced. In like manner, in singing, the small initial sound produced by the vibrating element of the voice-organs is reinforced by vibrations communicated to the air contained in the resonance chambers. (2) Next take an ordinary porcelain flower-vase. Sing a sonorous A (Italian) in the open, on the middle of the voice, then repeat the A with the mouth and nose inserted in the flower-vase, and the vowel-sound will be neutralised, and the vibration to a great extent suffocated. In like manner the sound which has been reinforced by the good position of some of the resonance chambers may be suffocated and spoiled by a bad position of any one of the remaining ones. These two experiments, simple as they are, are conclusive. (3) The third, less simple, consists in whispering the vowels. The five elementary sounds of language (the Italian vowels) will be found in the following order, I, E, A, O, U, or vice versa, each vowel giving a musical note dependent entirely upon the