For Minor Keys, the Neapolitans begin with Re; using Fa for an accidental Flat, and Mi for a Sharp. Durante, however, when his pupils were puzzled with a difficult Mutation, used to cry out, 'Only sing the syllables in tune, and you may name them after devils, if you like.'

The truth is, that, as long as the syllables are open, their selection is a matter of very slight importance. They were never intended to be used for the formation of the Voice, which may be much better trained upon the sound of the vowel, A, as pronounced in Italian, than upon any other syllable whatever. Their use is, to familiarise the Student with the powers and special peculiarities of the sounds which form the Scale: and here it is that the arguments of those who insist upon the use of a 'fixed,' or a 'moveable Do,' demand our most careful consideration. The fact that in Italy and France the syllables Ut (Do), Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, are always applied to the same series of notes, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and used as we ourselves use the letters, exercises no effect whatever upon the question at issue. It is quite possible for an Italian, or a Frenchman, to apply the 'fixed Do system' to his method of nomenclature, and to use the 'moveable Do' for purposes of Solmisation. The writer himself, when a child, was taught both systems simultaneously, by his first instructor, John Purkis, who maintained, with perfect truth, that each had its own merits, and each its own faults. In matters relating to absolute pitch, the fixed Do is all that can be desired. The 'moveable Do' ignores the question of pitch entirely; but it calls the Student's attention to the peculiar functions attached to the several Degrees of the Scale so clearly, that, in a very short time, he learns to distinguish the Dominant, the Sub-Mediant, the Leading-Note, or any other Interval of any given Key, without the possibility of mistake, and that, by simply sol-faing the passage in the usual manner.

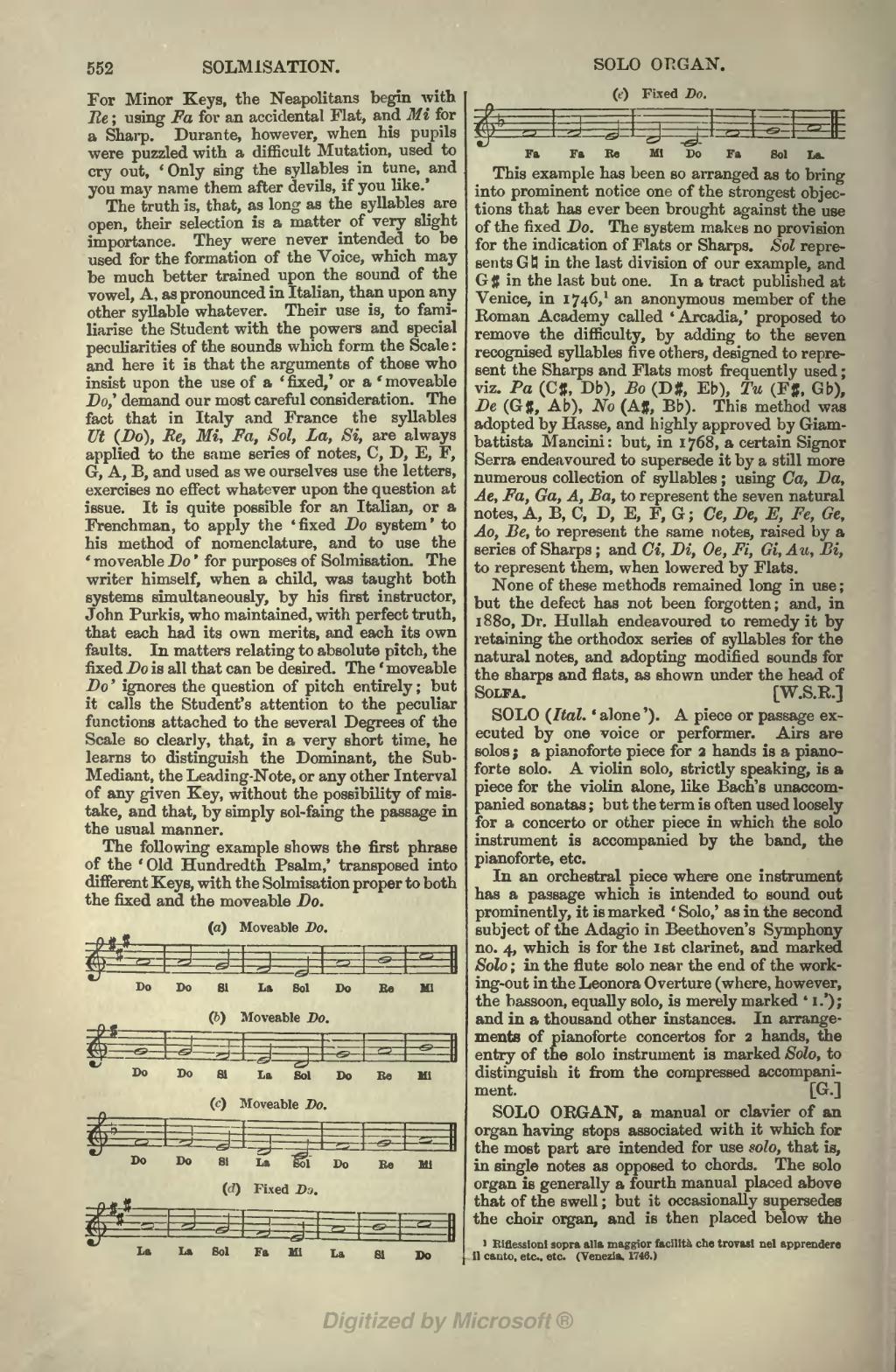

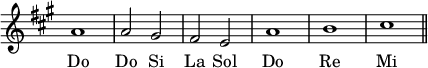

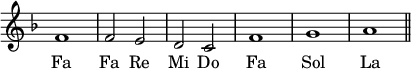

The following example shows the first phrase of the 'Old Hundredth Psalm,' transposed into different Keys, with the Solmisation proper to both the fixed and the moveable Do.

(a) Moveable Do.

(b) Moveable Do.

(c) Moveable Do.

(d) Fixed Do.

(e) Fixed Do.

This example has been so arranged as to bring into prominent notice one of the strongest objections that has ever been brought against the use of the fixed Do. The system makes no provision for the indication of Flats or Sharps. Sol represents G♮ in the last division of our example, and G♯ in the last but one. In a tract published at Venice, in 1746,[1] an anonymous member of the Roman Academy called 'Arcadia,' proposed to remove the difficulty, by adding to the seven recognised syllables five others, designed to represent the Sharps and Flats most frequently used; viz. Pa (C♯, D♭), Bo (D♯, E♭), Tu (F♯, G♭), De (G♯, A♭), No (A♯, B♭). This method was adopted by Hasse, and highly approved by Giambattista Mancini: but, in 1768, a certain Signor Serra endeavoured to supersede it by a still more numerous collection of syllables; using Ca, Da, Ae, Fa, Ga, A, Ba, to represent the seven natural notes, A, B, C, D, E, F, G; Ce, De, E, Fe, Ge, Ao, Be, to represent the same notes, raised by a series of Sharps; and Ci, Di, Oe, Fi, Gi, Au, Bi, to represent them, when lowered by Flats.

None of these methods remained long in use; but the defect has not been forgotten; and, in 1880, Dr. Hullah endeavoured to remedy it by retaining the orthodox series of syllables for the natural notes, and adopting modified sounds for the sharps and flats, as shown under the head of Solfa.

[ W. S. R. ]

SOLO (Ital. 'alone '). A piece or passage executed by one voice or performer. Airs are solos; a pianoforte piece for 2 hands is a pianoforte solo. A violin solo, strictly speaking, is a piece for the violin alone, like Bach's unaccompanied sonatas; but the term is often used loosely for a concerto or other piece in which the solo instrument is accompanied by the band, the pianoforte, etc.

In an orchestral piece where one instrument has a passage which is intended to sound out prominently, it is marked 'Solo,' as in the second subject of the Adagio in Beethoven's Symphony no. 4, which is for the 1st clarinet, and marked Solo; in the flute solo near the end of the working-out in the Leonora Overture (where, however, the bassoon, equally solo, is merely marked '1.'); and in a thousand other instances. In arrangements of pianoforte concertos for 2 hands, the entry of the solo instrument is marked Solo, to distinguish it from the compressed accompaniment.

[ G. ]

SOLO ORGAN, a manual or clavier of an organ having stops associated with it which for the most part are intended for use solo, that is, in single notes as opposed to chords. The solo organ is generally a fourth manual placed above that of the swell; but it occasionally supersedes the choir organ, and is then placed below the

- ↑ Riflessioni sopra alla maggior facilità che trovasi nel apprendere il canto, etc., etc. (Venezia, 1746.)