could find them; and among these were the familiar dance-tunes, which for a long while held a prominent position in the heterogeneous group of movements, and were only in late times transmuted into the Scherzo which supplanted the Minuet and Trio in one case, and the Finale or Rondo, which ultimately took the place of the Gigue, or Chaconne, or other similar dance-forms as the last member of the group.

The third source, as above mentioned, was the drama, and from this two general ideas were derivable: one from the short passages of instrumental prelude or interlude, and the other from the vocal portions. Of these, the first was intelligible in the drama through its relation to some point in the story, but it also early attained to a crude condition of form which was equally available apart from the drama. The other produced at first the vaguest and most rhapsodical of all the movements, as the type taken was the irregular declamatory recitative which appears to have abounded in the early operas.

It is hardly likely that it will ever be ascertained who first experimented in sonatas of several distinct movements. Many composers are mentioned in different places as having contributed works of the kind, such as Farina, Cesti, Graziani, among Italians, Rosenmüller among Germans, and John Jenkins among Englishmen. Burney also mentions a Michael Angelo Rossi, whose date is given as from about 1620 to 1660. An Andante and Allegro by him, given in Pauer's Alte Meister, require notice parenthetically as presenting a curious puzzle, if the dates are correct and the authorship rightly attributed. Though belonging to a period considerably before Corelli, they show a state of form which certainly was not commonly realised till more than a hundred years later. The distribution of subject-matter and key, and the clearness with which they are distinguished, are like the works of the middle of the 18th rather than the 17th century, and they belong absolutely to the Sonata order, and the conscious style of the later period. But as these stand alone it is not safe to infer anything from them. The actual structure of large numbers of sonatas composed in different parts of Europe soon after this time, proves a tolerably clear consent as to the arrangement and quality of the movements. A fine vigorous example is a Sonata in C minor for violin and figured bass, by H. J. F. Biber, a German, said to have been first published in 1681. This consists of five movements in alternate slow and quick time. The first is an introductory Largo of contrapuntal character, with clear and consistent treatment in the fugally imitative manner; the second is a Passacaglia, which answers roughly to a continuous string of variations on a short well-marked period; the third is a rhapsodical movement consisting of interspersed portions of Poco lento, Presto, and Adagio, leading into a Gavotte; and the last is a further rhapsodical movement alternating Adagio and Allegro. In this group the influence of the madrigal or canzona happens to be absent; the derivation of the movements being—in the first the contrapuntalism of the music of the church, in the second and fourth, dances, and in the third and fifth probably operatic or dramatic declamation. The work is essentially a violin sonata with accompaniment, and the violin-part points to the extraordinarily rapid advance to mastery which was made in the few years after its being accepted as an instrument fit for high-class music. The writing for the instrument is decidedly elaborate and difficult, especially in the double stops and contrapuntal passages which were much in vogue with almost all composers from this time till J. S. Bach. In the structure of the movements the fugal influences are most apparent, and there are very few signs of the systematic repetition of subjects in connection with well-marked distribution of keys, which in later times became indispensable.

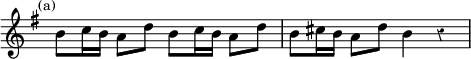

Similar features and qualities are shown in the curious set of seveA Sonatas for Clavier by Johann Kuhnau, called 'Frische Clavier Früchte,' etc., of a little later date; but there are also in some parts indications of an awakening sense of the relation and balance of keys. The grouping of the movements is similar to those of Biber, though not identical; thus the first three have five movements or divisions, and the remainder four. There are examples of the same kind of rhapsodical slow movements, as may be seen in the Sonata (No. 2 of the set) which is given in Pauer's Alte Meister; there are several fugal movements, some of them clearly and musically written; and there are some good illustrations of dance types, as in the last movement of No. 3, and the Ciaccona of No. 6. But more important for the thread of continuous development are the peculiar attempts to balance tolerably defined and distinct subjects, and to distribute key and subject in large expanses, of which there are at least two clear examples. In a considerable proportion of the movements the most noticeable method of treatment is to alternate two characteristic groups of figures or subjects almost throughout, in different positions of the scale and at irregular intervals of time. This is illustrated in the first movement of the Sonata No. 2, in the first movement of No. 1, and in the third movement of No. 5. The subjects in the last of these are as follows:—

The point most worth notice is that the device lies half-way between fugue and true sonata-form. The alternation is like the recurrence of subject and countersubject in the former, wandering hazily in and out, and forwards and backwards, between nearly allied keys, as would be the case in a fugue. But the subjects are not presented in