produced by shortening the first syllable and prolonging the second, thus:—

![{ \relative g' { \time 2/4

g16[ g8. g16 g8.] | g16 g8. \bar "||" s16_"etc." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/e/8egnpih9xorb0jdm3yjcl6y8zgu7cjm/8egnpih9.png)

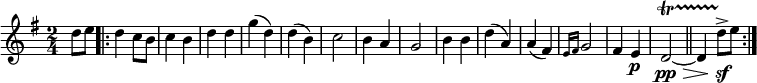

Indigenous to the Ukraine, and met with nowhere else, is a kind of epic song of irregular rhythm, recited to a slow monotonous chant. These Doumas (as they are called) were originally improvised by the Bandurists, but that class of wandering minstrels is now nearly extinct, and their function has devolved upon the native women who compose both the poetry and the melodies of the songs which they sing themselves. Among the peculiarities of these interesting songs we may mention that if a song of the Ukraine ends on the dominant or lower octave, the last note of the closing verse is sung very softly, and then without a break the new verse begins loud and accented, the only division between the two being such a shake as is described by the German phrase Bockhiller. Here is an example:—

Wendic folk-song.

This feature is common also to Cossack songs, and to the songs of that Wendic branch of the Slavonic race which is found in a part of Saxony. The Wendic songs (except when dance-tunes) are generally sung tremolando, and very slowly. And the exclamation 'Ha' or 'Haie,' with which they almost invariably commence, may be compared with the 'Hoj' or 'Ha' of Little Russia, the 'ach' of Great Russia, and the meaningless 'und' and 'aber' which are interspersed through German Volkslieder. To Lithuania belong the Dainos; and monotonous as they are, they are not without a certain grace, when sung by the people of their native districts. Servia, too, has her own characteristic songs, which often end on the supertonic, as for instance in the case of the Servian Hymn:—

This mode of ending may also be sometimes found in the songs of Bosnia and Dalmatia.

The folk-songs of Russia are always metrical, and the metre is wont to be very free and elastic. But, unlike modern Russian poetry, which imitates German poetry, and is written in four-line stanzas and rhyme, the genuine folksongs of Russia are never rhymed, and rarely sung with instrumental accompaniment. If, however, there be an accompaniment, the instruments most commonly used are the Gudok, a three-stringed fiddle; or the Dudka, a reed instrument of two small parallel pipes; or the Gusla, which resembles a cymbal. Being, therefore, written in a vocal rather than an instrumental style, the songs of Russia want brilliancy and variety of rhythm, but what they lose in these qualities they gain in tenderness and expression. A large proportion of Russian and other Slavonic songs are of Gipsy origin, and are usually in dance rhythm, the dancers marking the time by the stamp of their feet. In short, if we roughly divide the songs of Russia they will fall into two groups:—(1) songs of a quick lively tempo, commonly sung to dances, in major keys, and in unison; (2) songs sung very slow, in harmony, and in minor keys. Of the two the latter are the best and most popular. It will not escape notice that florid passages on one syllable[1] often occur in Russian songs, as in the 'Cossack of the Don':—

nor that some of the oldest Slavonic melodies are based on the ecclesiastical scales, more especially those of Poland and Bohemia, whose music bears the impress of contact with Germany.

The former feature has been well perpetuated by Rubinstein 'in his beautiful songs 'Gelb rollt'—

![{ << \new Voice = "this" \relative g' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \key bes \major

g4. aes32( bes c d) | ees4( d16[ ees] c d) |

ees4( d16[ ees] c d)_"etc." }

\new Lyrics \lyricmode { ne4. mein8 Herz2 und4. die8 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/8/l87bbwqrb4aw2wmqhf0ouy7zplhvg08/l87bbwqr.png)

and 'Die helle Sonne leuchtet'—

![{ \relative g'' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \key g \major

g4( fis16 g fis e e fis) e[ d] |

d[ e]^\markup \italic "rit." d c c( d c d) b[ c] b a_"etc." }

\addlyrics { al -- le _ glühn _ und _ zit -- tern } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/5/f5t4sv31bxac5l36oh0v9ppbcw93wgb/f5t4sv31.png)

The later composers of Russia, such as Glinka, Lvoff, Verstovsky, Dargomijsky, Kozlovsky, and others, have been true to the national spirit in their songs. So faithfully have the old national songs been imitated by them, that it is hard to distinguish the new from the old productions, and indeed some modern songs—for instance, Varlamof's 'Red Sarafan,' and Alabief's 'The Nightingale'—have been accepted as national melodies. Other composers, such as Gurilef, Vassilef, and Dübüque, have set a number of national airs, especially the so-called Gipsy tunes, to modern Russian words in rhyme and four-line stanzas, and have arranged them with PF. accompaniment. Even the greatest Russian composers, the style of whose other works is cosmopolitan, adhere to national peculiarities in their songs. The florid passages on one syllable, already noticed, are often met with in the songs of Rubinstein; and Tschaïkofsky frequently reproduces the characteristic harsh harmony of the

- ↑ Bach has a long and not dissimilar passage on the word 'weinete,' à propos to Peter's weeping, in his Passion Music of S. Matthew and S. John.