the burghers.[1] Poetry lost in grace and tenderness by the change, but it gained in strength and moral elevation. The reputed founder of the Meistersinger was Heinrich von Meissen, commonly called Frauenlob. He came to Mainz in 1311, and instituted a guild or company of singers who bound themselves to observe certain rules. Though often stiff and pedantic, Frauenlob's poems evince intelligence and thought;[2] and the example set by him was widely imitated. Guilds of singers soon sprang up in other large towns of Germany; and it became the habit of the burghers, especially in the long winter evenings, to meet together and read or sing narrative or other poems, either borrowed from the Minnesinger, and adapted to the rules of their own guild, or original compositions of their own. By the end of the 14th century there were regular schools of music at Colmar, Frankfurt, Mainz, Prague, and Strassburg. A little later they were found also in Nuremberg, Augsburg, Breslau, Regensburg, and Ulm. In short, during the 15th and 16th centuries there was scarcely a town of any magnitude or importance throughout Germany which had not its own Meistersinger. The 17th century was a period of decline both in numbers and repute. The last of these schools of music lingered at Ulm till 1839, and then ceased to exist; and the last survivor of the Meistersinger is said to have died in 1876.

Famous among Meistersinger were Hans Rosenblüt, Till Eulenspiegel, Muscatblüt, Heinrich von Mügeln, Puschmann, Fischart, and Seb. Brandt; but the greatest of all by far was Hans Sachs, the cobbler of Nuremberg, who lived from 1494 to 1576. Under him the Nuremberg school reached a higher point of excellence than was ever attained by any other similar school. His extant works are 6048 in number, and fill 34 folio volumes. 4275 of them are Meisterlieder, or 'Bar,' as they are called.[3] To Sachs's pupil, Adam Puschmann, we are indebted for accounts of the Meistergesang. They bear the titles of 'Gründlicher Bericht des deutschen Meistergesanges' (Görlitz 1573); and 'Gründlicher Bericht der deutschen Reimen oder Rhythmen' (Frankfurt a. O. 1596).[4]

The works of the Meistersinger had generally a sacred subject, and their tone was religious. Hymns were their lyrics, and narrative poems founded on Scripture were their epics. Sometimes, however, they wrote didactic or epigrammatic poems. But their productions were all alike wanting in grace and sensibility; and by a too rigid observance of their own minute and complicated rules of composition or 'Tablatur' (as they were termed), the Meistersinger constantly displayed a ridiculous pedantry.

Churches were their ordinary place of practice. At Nuremberg, for instance, their singing school was held in S. Katherine's church, and their public contests took place there. The proceedings commenced with the 'Freisingen,' in which any one, whether a member of the school or not, might sing whatever he chose; but no judgments were passed on these preliminary performances. After them came the real business of the day—the contest—in which Meistersinger alone might compete. They were limited to scriptural subjects, and their relative merits were adjudged by four 'Merker' or markers, who sat, behind a curtain, at a table near the altar. It was the duty of one of the four to see that the song faithfully adhered to scripture; of another to pay special attention to its prosody; of a third to its rhyme; and of the fourth to its melody. Each carefully noted and marked the faults made in his own province; and the competitor who had the fewest faults obtained the prize, a chain with coins. One of the coins, bearing the image of King David, had been the gift of Hans Sachs, and hence the whole 'Gesänge' were called the 'David,' and the prizemen were called the 'Davidwinner.' The second prize was a wreath of artificial flowers. Every Davidwinner might take pupils, but no charge was made for teaching. The term 'Meister,' strictly speaking, applied only to those who invented a new metre, or composed their own melodies; the rest were simple 'Sänger.' The instruments employed for accompaniments were the harp, the violin, and the cither.

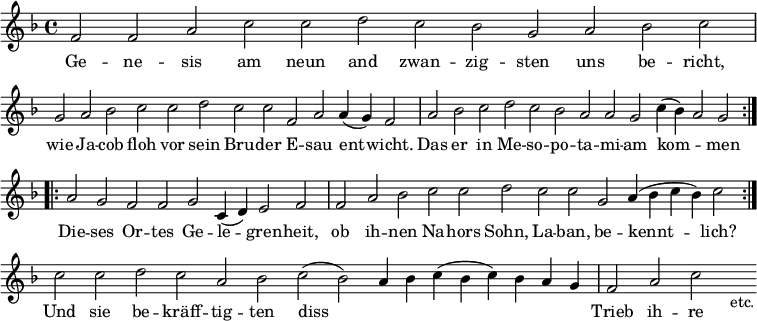

The Meistersinger seem to have possessed a store of melodies for their own use: and these melodies were labelled, as it were, with distinctive though apparently unmeaning names, such as the blue-tone, the red-tone, the ape-tune, the rosemary-tune, the yellow-lily-tune, etc. A Meistersinger might set his poems to any of these melodies. The four principal were called the 'gekrönten Töne,' and their respective authors were Müglin, Frauenlob, Marner, and Regenbogen. So far were the Meistersinger carried by their grotesque pedantry, that in setting the words of the 29th chapter of Genesis to Heinrich Müglin's 'lange Ton,' the very name of the book and the number of the chapter were included;[5] thus—

- ↑ The origin of the term 'Meistersinger' is uncertain. Ambros says that it was applied to every Minnesinger who was not a noble, and thus became the distinguishing appellation of the burgher minstrels. Reissmann, however, maintains that the title Meister indicated excellence in any act or trade; and that having been at first conferred only on the best singers, it was afterwards extended to all members of the guilds.

- ↑ A complete collection of Frauenlob's poems was published in 1843 by Ettmüller at Quedlinburg.

- ↑ The celebrated chorale 'Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz' was long believed to be the work of Hans Sachs; but it has been conclusively shown by Böhme in his 'Altdeutsches Liederbuch,' p. 748, that the words were written by Georgius Aemilius Oemler, and then set to the old secular melody Dein gsund mein freud.'

- ↑ Both are partially reprinted in Büsching's 'Sammlung für altdeutsche Literatur.'

- ↑ A similar thing occurs in the 'Lamentations' of the Roman Church, which begin 'Incipit Lamentatio Jeremiæ prophetæ. Aleph.'