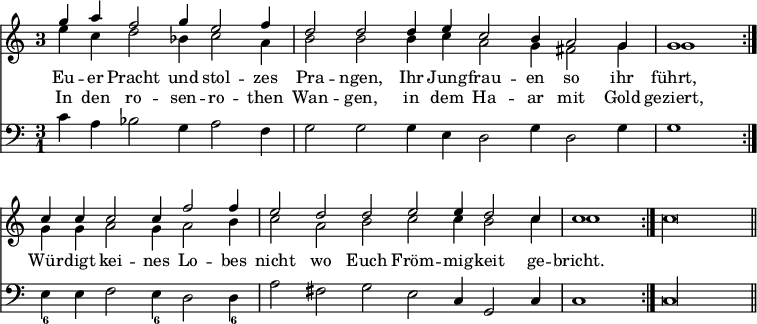

[see Albert], set his own and his associates' songs to music. His compositions became extremely popular; and he has been styled 'the father of the volksthümliches Lied.' Schein and Hammerschmidt had preceded him on the right path, but their taste and talent were frustrated by the worthlessness of the words they set to music. The poetry on which Albert worked was not by any means of a high order, nor was he its slave, but it had sufficient merit to demand a certain measure of attention. This Albert gave to it, and he wrote melodiously. Several of his songs are for one voice with clavicembalo accompaniment, but their harmony is poor, as the following example shows[1]:—

The movement begun by Albert was earned on by Ahle, and the Kriegers, Adam and Johann. Johann's songs are very good, and exhibit a marked improvement in grace and rhythm. The first bars of his song 'Kommt, wir wollen ' have all the clearness of the best Volkslieder:—

![{ << \new Staff \relative b' { \key f \major \time 3/2 \once \override Staff.TimeSignature.style = #'single-digit

bes2 f4 bes4. a8( bes4) | c( d) ees d4.( c8) bes4 | %eol1

bes2 f4 c'4.( bes8) a4 | g4. a8 bes4 a2. | s4_"etc." }

\addlyrics { Kommt, wir wol -- len uns spa -- zle -- ren

weil die Zeit so gün -- _ stig ist. }

\new Staff \relative b, { \key f \major \clef bass

bes2 a4 g2. | a bes |

d e2 f4 | bes,2 a4 f4. e8[ d c] s4 }

\figures { s2 <6>4 s2. | <6 5> s |

<6> <6> | <5>8 <6> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/s/bs6o8vt2yqk0fy32cosys69o9wp4gev/bs6o8vt2.png)

Meanwhile the Kunstlied or, polyphonic song had ceased to advance: other branches, especially instrumental and dramatic music, had absorbed composers, and songs began to be called 'Odes' and 'Arias.' Writing in 1698, Keiser says that cantatas had driven away the old German songs, and that their place was being taken by songs consisting of recitatives and arias mixed.[2] Among the writers of the 18th century who called their songs 'arias,' and who wrote chiefly in the aria form, were Graun, Agricola, Sperontes, Telemann, Quantz, Doles, Kirnberger, C. P. E. Bach, Nichelmann, Marpurg, and Neefe (Beethoven's master). They certainly rendered some services to the Song. They set a good example of attention to the words, both as regards metre and expression; they varied the accompaniment by the introduction of arpeggios and open chords; and they displayed a thorough command of the strophical form. But, notwithstanding these merits, their songs, with few exceptions, must be pronounced to be dry, inanimate, and deficient in melody.[3]

It might strike the reader as strange if the great names of J. S. Bach and Handel were passed by in silence; but, in truth, neither Bach nor Handel ever devoted real study to the Song. Such influence as they exercised upon it was indirect. Bach, it is true, wrote a few secular songs, and one of them was the charming little song 'Willst du dein Herz mir schenken,' which is essentially 'volksthümlich':[4]

![{ \relative e' { \key ees \major \time 4/4 \partial 8 \autoBeamOff

ees8 | ees g bes ees ees d r g |

f16[ d] c[ bes] aes8 aes \grace aes g4 }

\addlyrics { Willst du dein Herz mir schenk -- en, So fang es heim -- lich an } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/8/28sklhq5n541cgqzdq4szaoy092o4fd/28sklhq5.png)

His two comic cantatas also contain several of great spirit; but it was through his choral works that he most powerfully affected the Song. The only English song which Handel is known to have written is a hunting-song for bass voice,[5] of which we give the opening strain:—

![{ \relative a' { \key d \major \time 3/8 \autoBeamOff \partial 16

a8*1/2 | d d d d cis16*1/2[ d] b8*1/2 | e e e e4*1/2 e,8*1/2 | %eol1

a a d a b16*1/2[ a] g[ fis] | g8*1/2 e cis' d4*1/2 }

\addlyrics { The morn -- ing is charm -- ing, all Na -- ture is gay,

A -- way, my brave boys, to your hor -- ses a -- way! } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/9/m9lag5ng2ry6xb33a1ohvqu4nos9dql/m9lag5ng.png)

but his influence upon the Song was through his operas and oratorios, and there it was immense.[6] Equally indirect, as will be seen presently, were the effects produced on it by the genius of Gluck, Haydn, and even of Mozart.

At the period we have now reached, namely the end of the 18th century, a new and popular form of the Kunstlied appeared, and this was the 'volksthümliches Lied.'[7] The decline of the Volkslied during the 17th century has been sometimes attributed to the distracted state of Germany; and certainly the gloomy atmosphere of the Thirty Years War and the desolation of

- ↑ In this song the voice has the upper melody, and the clavicembalo the two under parts.

- ↑ See the preface to his Cantata collection. See also Lindner, 'Geschichte des deutschen Liedes im xviii Jahrhundert,' p. 53.

- ↑ Full information respecting these songs, and abundant examples will be found in Lindner's work referred to in the preceding note.

- ↑ But the authenticity of this is much questioned by Spitta (Bach i. 834).

- ↑ In the Fitzwilliam Library at Cambridge.

- ↑ See Schneider, 'Das musikalische Lied.' vol. iii. p. 190.

- ↑ The term 'volksthümliches Lied,' defies exact translation; but speaking broadly, means a simple popular form of the artistic song.