way in which the scenes and characters were individualised. On the other hand there were great shortcomings which could not be ignored. These chiefly lay—outside a certain monotony in the movements—in the harmony. When Berlioz afterwards ventured to maintain that scarcely two real faults in harmony could be pointed out in the score, he only showed how undeveloped was his own sense of logical harmony. It is in what is called unerring instinct for the logic of harmony that Spontini so sensibly falls short in 'La Vestale.'

This no doubt arose from the fact that his early training in Naples was insufficient to develop the faculty, and that when he had discovered the direction in which his real strength lay it was too late to remedy the want. Zelter, who in reference to Spontini never conceals his narrowmindedness, made a just remark when he said that the composer of the Vestale would never rise to anything much higher than he was then, if he were over 25 at the time that it was written.[1] He never really mastered a great part of the material necessary for the principal effects in his grand operas. His slow and laborious manner of writing, too, which he retained to the last, though creditable to his conscientiousness as an artist, is undoubtedly to be attributed in part to a sense of uncertainty.

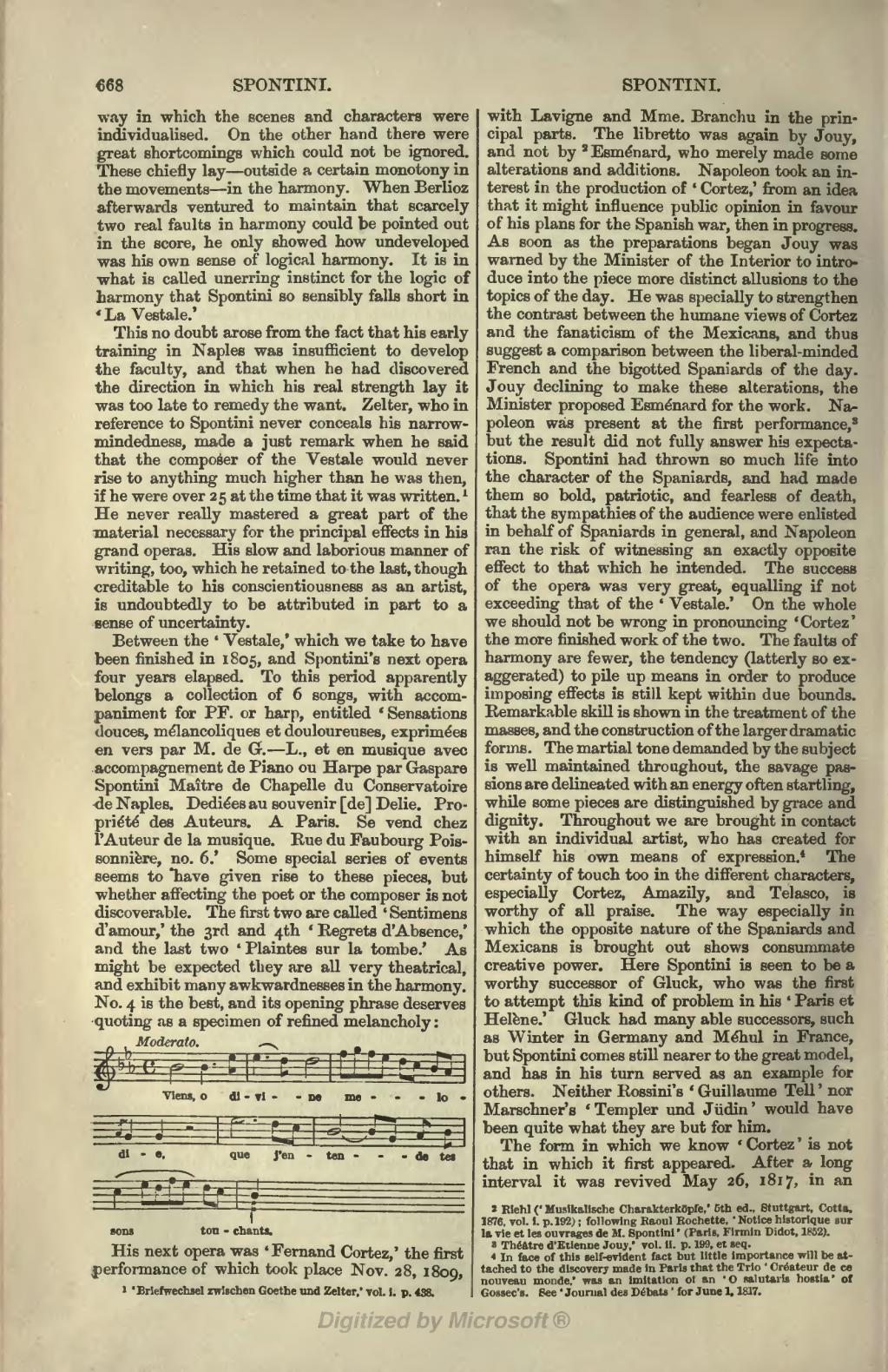

Between the 'Vestale,' which we take to have been finished in 1805, and Spontini's next opera four years elapsed. To this period apparently belongs a collection of 6 songs, with accompaniment for PF. or harp, entitled 'Sensations douces, mélancoliques et douloureuses, exprimées en vers par M. de G.—L., et en musique avec accompagnement de Piano ou Harpe par Gaspare Spontini Maître de Chapelle du Conservatoire de Naples. Dediées au souvenir [de] Delie. Propriété des Auteurs. A Paris. Se vend chez l'Auteur de la musique. Rue du Faubourg Poissonniere, no. 6.' Some special series of events seems to have given rise to these pieces, but whether affecting the poet or the composer is not discoverable. The first two are called 'Sentimens d'amour,' the 3rd and 4th 'Regrets d'Absence,' and the last two 'Plaintes sur la tombe.' As might be expected they are all very theatrical, and exhibit many awkwardnesses in the harmony. No. 4 is the best, and its opening phrase deserves quoting as a specimen of refined melancholy:

![{ << \new Staff \relative b' { \key ees \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Moderato." \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

bes2 bes4. ees8 | ees4.( d8) d2 | f8 g f ees d c bes[ aes] | %eol1

\acciaccatura aes8 g4 g r2 | ees'2. d8 c |

bes2 ~ bes8 g aes\noBeam bes | %end line 2

c4( ees8[ d f ees]) d c | << { bes4 } \\ { \tiny <g ees> } >> s }

\new Lyrics \lyricmode { Viens,2 o4. di8 -- vi2 -- ne me2. -- lo4 --

di -- e,2. que j'en4 -- ten2. -- de8 tes

sons2. ton4 -- chants.4 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/b/nb1mqoe53rrfx8jhzcllhw8kw56xiag/nb1mqoe5.png)

His next opera was 'Fernand Cortez,' the first performance of which took place Nov. 28, 1809, with Lavigne and Mme. Branchu in the principal parts. The libretto was again by Jouy, and not by [2]Esménard, who merely made some alterations and additions. Napoleon took an interest in the production of 'Cortez,' from an idea that it might influence public opinion in favour of his plans for the Spanish war, then in progress. As soon as the preparations began Jouy was warned by the Minister of the Interior to introduce into the piece more distinct allusions to the topics of the day. He was specially to strengthen the contrast between the humane views of Cortez and the fanaticism of the Mexicans, and thus suggest a comparison between the liberal-minded French and the bigotted Spaniards of the day. Jouy declining to make these alterations, the Minister proposed Esménard for the work. Napoleon was present at the first performance,[3] but the result did not fully answer his expectations. Spontini had thrown so much life into the character of the Spaniards, and had made them so bold, patriotic, and fearless of death, that the sympathies of the audience were enlisted in behalf of Spaniards in general, and Napoleon ran the risk of witnessing an exactly opposite effect to that which he intended. The success of the opera was very great, equalling if not exceeding that of the 'Vestale.' On the whole we should not be wrong in pronouncing 'Cortez' the more finished work of the two. The faults of harmony are fewer, the tendency (latterly so exaggerated) to pile up means in order to produce imposing effects is still kept within due bounds. Remarkable skill is shown in the treatment of the masses, and the construction of the larger dramatic forms. The martial tone demanded by the subject is well maintained throughout, the savage passions are delineated with an energy often startling, while some pieces are distinguished by grace and dignity. Throughout we are brought in contact with an individual artist, who has created for himself his own means of expression.[4] The certainty of touch too in the different characters, especially Cortez, Amazily, and Telasco, is worthy of all praise. The way especially in which the opposite nature of the Spaniards and Mexicans is brought out shows consummate creative power. Here Spontini is seen to be a worthy successor of Gluck, who was the first to attempt this kind of problem in his 'Paris et Helene.' Gluck had many able successors, such as Winter in Germany and Méhul in France, but Spontini comes still nearer to the great model, and has in his turn served as an example for others. Neither Rossini's 'Guillaume Tell' nor Marschner's 'Templer und Jüdin' would have been quite what they are but for him.

The form in which we know 'Cortez' is not that in which it first appeared. After a long interval it was revived May 26, 1817, in an

- ↑ 'Briefwechsel zwischen Goethe und Zelter,' vol. i. p. 488.

- ↑ Riehl ('Musikalische Charakterköpfe,' 5th ed., Stuttgart, Cotta. 1876, vol. i. p. 192); following Raoul Rochette, 'Notice historique sur la vie et les ouvrages de M. Spontini' (Paris, Firmin Didot, 1852).

- ↑ 'Théâtre d'Etienne Jouy,' vol. ii. p. 199, et seq.

- ↑ In face of this self-evident fact but little importance will be attached to the discovery made in Paris that the Trio 'Créateur de ce nouveau monde,' was an imitation of an 'O salutaris hostia' of Gossec's. See 'Journal des Débats' for June 1, 1817.