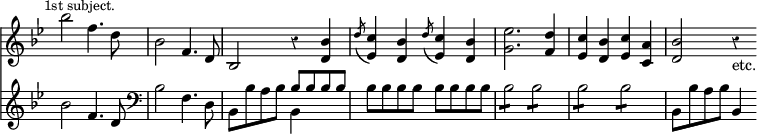

examples from the first movement of the fifth symphony of Stamitz's opus 9 illustrate both the style and the degree of contrast between the two principal subjects,

The style is a little heavy, and the motion constrained, but the general character is solid and dignified. The last movements of this period are curiously suggestive of some familiar examples of a maturer time; very gay and obvious, and very definite in outline. The following is very characteristic of Abel:—

It is a noticeable fact in connection with the genealogy of these works, that they are almost as frequently entitled 'Overture' as 'Symphony'; sometimes the same work is called by the one name outside and the other in; and this is the case also with some of the earlier and slighter symphonies of Haydn, which must have made their appearance about this period. One further point which it is of importance to note is that in some of Stamitz's symphonies the complete form of the mature period is found. One in D is most complete in every respect. The first movement is Allegro with double bars and repeats in regular binary form; the second is an Andante in G, the third a Minuet and Trio, and the fourth a Presto. Another in E♭ (which is called no. 7 in the part-books) and another in F (not definable) have also the Minuet and Trio. A few others by Schwindl and Ditters have the same, but it is impossible to get even approximately to the date of their production, and therefore little inference can be framed upon the circumstance, beyond the fact that composers were beginning to recognise the fourth movement as a desirable ingredient.

Another composer who precedes Haydn in time as well as in style is Emmanuel Bach. He was his senior in years, and began writing symphonies in 1741, when Haydn was only nine years old. His most important symphonies were produced in 1776; while Haydn's most important examples were not produced till after 1790. In style Emmanuel Bach stands singularly alone, at least in his finest examples. It looks almost as if he purposely avoided the form which by 1776 must have been familiar to the musical world. It has been shown that the binary form was employed by some of his contemporaries in their orchestral works, but he seems determinedly to avoid it in the first movements of the works of that year. His object seems to have been to produce striking and clearly outlined passages, and to balance and contrast them one with another according to his fancy, and with little regard to any systematic distribution of the successions of key. The boldest and most striking subject is the first of the Symphony in D:—