same time less fatiguing than the movement from the elbow. Single-note passages can be executed from the wrist in a more rapid tempo than is possible by means of finger-staccato.

In wrist-touch, the fore-arm remains quiescent in a horizontal position, while the keys are struck by a rapid vertical movement of the hand from the wrist joint. The most important application of wrist-touch is in the performance of brilliant octave-passages; and by practice the necessary flexibility of wrist and velocity of movement can be developed to a surprising extent, many of the most celebrated executants, among whom may be specially mentioned Alexander Dreyschock, having been renowned for the rapidity and vigour of their octaves. Examples of wrist octaves abound in pianoforte music from the time of Clementi (who has an octave-study in his Gradus, No. 65), but Beethoven appears to have made remarkably little use of octave-passages, the short passages in the Finale of the Sonata in C, Op. 2, No. 3, and the Trio of the Scherzo of the Sonata in C minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 30, No. 2, with perhaps the long unison passage in the first movement of the Concerto in E♭ (though here the tempo is scarcely rapid enough to necessitate the use of the wrist), being almost the only examples. A fine example of wrist-touch, both in octaves and chords, is afforded by the accompaniment to Schubert's 'Erl King.'

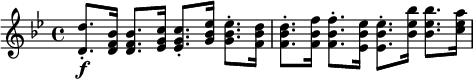

In modern music, passages requiring a combination of wrist and finger movement are sometimes met with, where the thumb or the little finger remains stationary, while repeated single notes or chords are played by the opposite side of the hand. In all these cases, examples of which are given below, although the movements of the wrist are considerably limited by the stationary finger, the repetition is undoubtedly produced by true wrist-action, and not by finger-movement. Adolph Kullak (Kunst des Anschlags) calls this 'half-wrist touch' (halbes Handgelenk).

Schumann, 'Reconnaisance' (Carneval).

Thalberg, 'Mose in Egitto.'

In such frequent chord-figures as the following, the short chord is played with a particularly free and loose wrist, the longer one being emphasized by a certain pressure from the arm.

Mendelssohn, Cello Sonata (Op. 45).

Such passages, if in rapid tempo, would be nearly impossible if played entirely from the elbow.

[ F. T. ]

WÜERST, Richard Ferdinand, composer and critic, born at Berlin, Feb. 22, 1824; died there Oct. 9, 1881. Was a pupil of Rungenhagen's at the Academy, of Hubert, Ries, and David in violin, and of Mendelssohn in composition. After touring for a couple of years, he settled at his native place and became in 1856 K. Musikdirector, in 1874 Professor, and 1877 Member, of the Academy of Arts. He was for many years teacher of composition in Kullak's Conservatorium. He contributed to the 'Berliner Fremdenblatt,' and in 1874–5 edited the 'Berliner Musikzeitung.' His works comprise five operas, symphonies, overtures, quartets, etc. None are known in this country. He died Oct. 9, 1881.

[ G. ]

WÜLLNER, Franz, born Jan. 28, 1832, at Munster, son of a distinguished philologist, director of the Gymnasium at Düsseldorf. Franz attended the Gymnasium of Münster till 1848, and passed the final examination; studying the piano and composition with Carl Arnold up to 1846, and afterwards with Schindler. In 1848 Wüllner followed Schindler to Frankfort, and continued his studies with him and F. Kessler till 1852. The winter of 1852–3 he passed in Brussels, frequently playing in public, and enjoying the society of Fétis, Kufferath, and other musicians. As a pianist he confined himself almost entirely to Beethoven's concertos and sonatas, especially the later ones. He then made a concert-tour through Bonn, Cologne, Bremen, Münster, etc., and spent some little time in Hanover and Leipzig. In March 1854 he arrived in Munich, and on Jan. 1, 1856, became PF. Professor at the Conservatorium there. In 1858 he became music-director of the town of Aix-la-Chapelle, being elected unanimously out of fifty-four candidates. Here he conducted the subscription concerts, and the vocal and orchestral unions. He turned his attention mainly to the orchestra and chorus, and introduced for the first time many of the great works to the concert-hall of Aix. In 1861 he received the title of Musikdirector to the King of Prussia, and in 1864 was joint-conductor with Rietz of the 41st Lower Rhine Festival.

In the autumn of 1864 Wüllner returned to Munich as court-Capellmeister to the King. His duty was to conduct the services at the court-church, and while there he reorganised the choir, and added to the répertoire many fine church-works, especially of the early Italian school. He also organised concerts for the choir, the programmes of which included old Italian, old German, and modern music, sacred and secular. In the autumn of 1867 he took the organisation and direction of the vocal classes in the king's new School of Music, and on Bülow's resignation the whole production department came into his hands, with the title of 'Inspector of the School of Music,' and in 1875 of 'Professor Royal.' During this time he wrote his admirable 'Choral Exercises