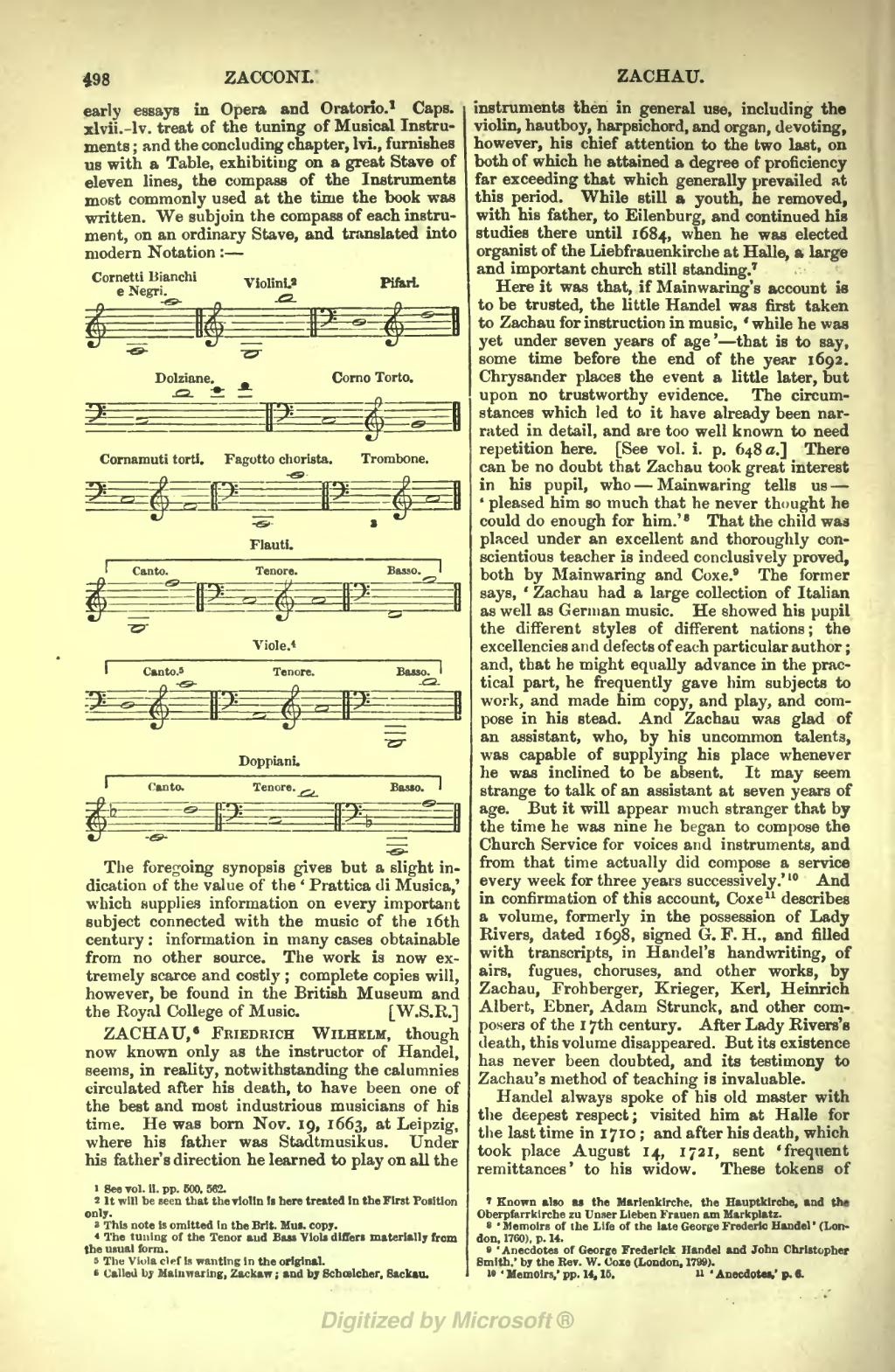

early essays in Opera and Oratorio.[1] Caps, xlvii.–lv. treat of the tuning of Musical Instruments; and the concluding chapter, lvi., furnishes us with a Table, exhibiting on a great Stave of eleven lines, the compass of the Instruments most commonly used at the time the book was written. We subjoin the compass of each instrument, on an ordinary Stave, and translated into modern Notation:—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Cornetti Bianchi e Negri Violini[2] Pifari Dolziane. Corno Torto. Cornamuti torti. Fagotto chorista. Trombone.[3] Flauti. Canto. Tenore. Basso. Viole.[4] Canto.[5] Tenore. Basso. Doppiani. Canto. Tenore. Basso.

The foregoing synopsis gives but a slight indication of the value of the 'Prattica di Musica,' which supplies information on every important subject connected with the music of the 16th century: information in many cases obtainable from no other source. The work is now extremely scarce and costly; complete copies will, however, be found in the British Museum and the Royal College of Music.

[ W. S. R. ]

ZACHAU,[6] Friedrich Wilhelm, though now known only as the instructor of Handel, seems, in reality, notwithstanding the calumnies circulated after his death, to have been one of the best and most industrious musicians of his time. He was born Nov. 19, 1663, at Leipzig, where his father was Stadtmusikus. Under his father's direction he learned to play on all the instruments then in general use, including the violin, hautboy, harpsichord, and organ, devoting, however, his chief attention to the two last, on both of which he attained a degree of proficiency far exceeding that which generally prevailed at this period. While still a youth, he removed, with his father, to Eilenburg, and continued his studies there until 1684, when he was elected organist of the Liebfrauenkirche at Halle, a large and important church still standing.[7]

Here it was that, if Mainwaring's account is to be trusted, the little Handel was first taken to Zachau for instruction in music, 'while he was yet under seven years of age'—that is to say, some time before the end of the year 1692. Chrysander places the event a little later, but upon no trustworthy evidence. The circumstances which led to it have already been narrated in detail, and are too well known to need repetition here. [See vol. i. p. 648a.] There can be no doubt that Zachau took great interest in his pupil, who—Mainwaring tells us—'pleased him so much that he never thought he could do enough for him.'[8] That the child was placed under an excellent and thoroughly conscientious teacher is indeed conclusively proved, both by Mainwaring and Coxe.[9] The former says, 'Zachau had a large collection of Italian as well as German music. He showed his pupil the different styles of different nations; the excellencies and defects of each particular author; and, that he might equally advance in the practical part, he frequently gave him subjects to work, and made him copy, and play, and compose in his stead. And Zachau was glad of an assistant, who, by his uncommon talents, was capable of supplying his place whenever he was inclined to be absent. It may seem strange to talk of an assistant at seven years of age. But it will appear much stranger that by the time he was nine he began to compose the Church Service for voices and instruments, and from that time actually did compose a service every week for three years successively.'[10] And in confirmation of this account, Coxe[11] describes a volume, formerly in the possession of Lady Rivers, dated 1698, signed G. F. H., and filled with transcripts, in Handel's handwriting, of airs, fugues, choruses, and other works, by Zachau, Frohberger, Krieger, Kerl, Heinrich Albert, Ebner, Adam Strunck, and other composers of the 17th century. After Lady Rivers's death, this volume disappeared. But its existence has never been doubted, and its testimony to Zachau's method of teaching is invaluable.

Handel always spoke of his old master with the deepest respect; visited him at Halle for the last time in 1710; and after his death, which took place August 14, 1721, sent 'frequent remittances' to his widow. These tokens of

- ↑ See vol. ii. pp. 500, 562.

- ↑ It will be seen that the violin is here treated in the First Position only.

- ↑ This note is omitted in the Brit. Mus. copy.

- ↑ The tuning of the Tenor and Bass Viols differs materially from the usual form.

- ↑ The Viola clef is wanting in the original.

- ↑ Called by Mainwaring, Zackaw; and by Schœlcher, Sackau.

- ↑ Known also as the Marienkirche, the Hauptkirche, and the Oberpfarrkirche zu Unser Lieben Frauen am Markplatz.

- ↑ 'Memoirs of the Life of the late George Frederic Handel' (London, 1760), p. 14.

- ↑ 'Anecdotes of George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith,' by the Rev. W. Coxe (London, 1799).

- ↑ 'Memoirs,' pp. 14, 15.

- ↑ 'Anecdotes,' p. 6.