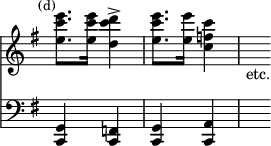

the result is to unify the impression of the whole movement, and to give it a special sentiment in an unusual degree. In the first movement of the Symphony in D there are even several subjects in each section, but they are so interwoven with one another, and seem so to fit and illustrate one another, that for the most part there appears to be but little loss of direct continuity. In several cases we meet with the devices of transforming and transfiguring an idea. The most obvious instance is in the Allegretto of the Symphony in D, in which the first Trio in 2-4 time (a) is radically the same subject as that of the principal section in 3-4 time (b), but very differently stated. Then a very important item in the second Trio is a version in 3-8 time (c) of a figure of the first Trio in 2-4 time (d).

![{ << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \new Staff << \key g \major \mark \markup \small "(a)"

\new Voice \relative b' { \stemUp

b8[ b b c^>] | b[ b b e^>] | s_"etc." }

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown

<d g>8[ q q <c g'>] | <d g>8[ q q <fis a>] } >>

\new Staff \relative g { \key g \major \clef "bass"

g'8 r r e-> | g r r c, | s } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/e/be66o6w9tp5pkn2tlbwyq6bx3ymplq0/be66o6w9.png)

Of similar nature, in the Symphony in C minor, are the suggestions of important features of subjects and figures of the first Allegro in the opening introduction, and the connection of the last movement with its own introduction by the same means. In all these respects Brahms illustrates the highest manifestations of actual art as art; attaining his end by extraordinary mastery of both development and expression. And it is most notable that the great impression which his larger works produce is gained more by the effect of the entire movements than by the attractiveness of the subjects. He does not seem to aim at making his subjects the test of success. They are hardly seen to have their full meaning till they are developed and expatiated upon in the course of the movement, and the musical impression does not depend upon them to anything like the proportionate degree that it did in the works of the earlier masters. This is in conformity with the principles of progress which have been indicated above. The various elements of which the art-form consists seem to have been brought more and more to a fair balance of functions, and this has necessitated a certain amount of 'give and take' between them. If too much stress is laid upon one element at the expense of others, the perfection of the art-form as a whole is diminished thereby. If the effects of orchestration are emphasised at the expense of the ideas and vitality of the figures, the work may gain in immediate attractiveness, but must lose in substantial worth. The same may be said of over-predominance of subject-matter. The subjects need to be noble and well marked, but if the movement is to be perfectly complete, and to express something in its entirety and not as a string of tunes, it will be a drawback if the mere faculty for inventing a striking figure or passage of melody preponderates excessively over the power of development; and the proportion in which they are both carried upwards together to the highest limit of musical effect is a great test of the artistic perfection of the work. In these respects Brahms's Symphonies are extraordinarily successful. They represent the austerest and noblest form of art in the strongest and healthiest way; and his manner and methods have already had some influence upon the younger and more serious composers of the day.

It would be invidious, however, to endeavour to point out as yet those in whose works his influence is most strongly shown. It must suffice to record that there are still many composers alive who are able to pass the symphonic ordeal with some success. Amongst the elders are Benedict and Hiller, who have given the world examples in earnest style and full of vigour and good workmanship. Among the younger representatives the most successful are the Bohemian composer Dvořak, and the Italian Sgambati; and among English works may be mentioned with much satisfaction the Norwegian [App. p.798 "Scandinavian"] Symphony of Cowen, which was original and picturesque in thought and treatment; the Elegiac Symphony of Stanford, in which excellent workmanship, vivacity of ideas, and fluency of development combine to establish it as an admirable example of its class; and an early symphony by Sullivan, which had such marks of excellence as to show how much art might have gained if circumstances had not drawn him to more lucrative branches of composition. It is obvious that composers have not given up hopes of developing something individual and complete in this form of art. It is not likely that many will be able to follow Brahms in his severe and uncompromising methods; but he himself has shown more than any one how elastic the old principles