9 by Giles Farnaby; 7 by Edward Blancks; 5 by John Douland; 5 by William Cobbold; 4 by Edmund Hooper; 2 by Edward Johnson, and 1 by Michael Cavendish. It will be observed that though most of these composers are eminent as madrigalists, none of them, except Hooper, and perhaps Johnson, are known as experts in the ecclesiastical style: a certain interest therefore belongs to their settings of plainsong; a kind of composition which they have nowhere attempted except in this work.[1] The method of treatment is very varied: in some cases the counterpoint is perfectly plain; in others plain is mixed with florid; while in others again the florid prevails throughout. In the plain settings no great advance upon the best of those in Day's Psalter will be observed. Indeed, in one respect,—the melodious progression of the voices,—advance was scarcely possible; since equality of interest in the parts had been, from the very beginning, the fundamental principle of composition. What advance there is will be found to be in the direction of harmony. The ear is gratified more often than before by a harmonic progression appropriate to the progression of the tune. Modulation in the closes, therefore, becomes more frequent; and in some cases, for special reasons, a partial modulation is even introduced in the middle of a section. In all styles, a close containing the prepared fourth, either struck or suspended, and accompanied by the fifth, is the most usual termination; but the penultimate harmony is also sometimes preceded by the sixth and fifth together upon the fourth of the scale. The plain style has been more often, and more successfully, treated by Blancks than by any of the others. He contrives always to unite solid and reasonable harmony with freedom of movement and melody in the parts; indeed, the melody of his upper voice is often so good that it might be sung as a tune by itself. But by far the greater number of the settings in this work are in the mixed style, in which the figuration introduced consists chiefly of suspended concords (discords being still reserved for the closes), passing notes, and short points of imitation between two of the parts at the beginning of the section. It is difficult to say who is most excellent in this manner. Farmer's skill in contriving the short points of imitation is remarkable, but one must also admire the richness of Hooper's harmony, Allison's smoothness, and the ingenuity and resource shown by Cobbold and Kirbye. The two last, also, are undoubtedly the most successful in dealing with the more florid style, which, in fact, and perhaps for this reason, they have attempted more often than any of their associates. They have produced several compositions of great beauty, in which most of the devices of counterpoint have been introduced, though without ostentation or apparent effort.

Farnaby and Johnson were perhaps not included in the original scheme of the work, since they do not appear till late, Johnson's first setting being Ps. ciii. and Farnaby's Ps. cxix. They need special, but not favourable, mention; because, although their compositions are thoroughly able, and often beautiful—Johnson's especially so—it is they who make it impossible to point to Este's Psalter as a model throughout of pure writing. The art of composing for concerted voices in the strict diatonic style had reached, about the year 1580, probably the highest point of excellence it was capable of. Any change must have been for the worse, and it is in Johnson and Farnaby that we here see the change beginning.[2]

There is, however, one Psalter which can be said to show the pure Elizabethan counterpoint in perfection throughout. It is entirely the work of one man, Richard Allison, already mentioned as one of Este's contributors, who published it in 1599, with the following title:

The Psalmes of David in Meter, the plaine song beeing the common tunne to be sung and plaide upon the Lute, Orpharyon, Citterne or Base Violl, severally or altogether, the singing part to be either Tenor or Treble to the instrument, according to the nature of the voyce, or for fowre voyces. With tenne short Tunnes in the end, to which for the most part all the Psalmes may be usually sung, for the use of such as are of mean skill, and whose leysure least serveth to practize. By Richard Allison Gent. Practitioner in the Art of Musicke, and are to be solde at his house in the Dukes place neere Alde-Gate London, printed by William Barley, the asigné of Thomas Morley. 1599.

The style of treatment employed by Allison in this work—in which he has given the tune to the upper voice throughout—is almost the same as the mixed style adopted by him in Este's Psalter. Here, after an interval of seven years, we find a slightly stronger tendency towards the more florid manner, but his devices and ornaments are still always in perfectly pure taste.[3] The lute part was evidently only intended for use when the tune was sung by a single voice, since it is constructed in the manner then proper to lute accompaniments to songs, in which the notes taken by the voice were omitted. Sir John

- ↑ Farmer had published, in the previous year, forty canons, two in one, upon one plainsong. These however were only contrapuntal exercises.

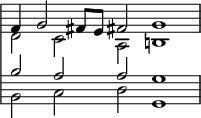

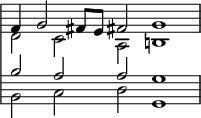

- ↑ Johnson (Ps. cxl.) has taken the fourth unprepared in a chord of the 6-4, and the imperfect triad with the root in the bass. Farnaby so frequently abandons the old practice of making all the notes upon one syllable conjunct, that one must suppose he actually preferred the leap in such cases. The following variants of a well-known cadence, also, have a kind of interest, since it is difficult to see how they could for a moment have borne comparison with their original:—

G. Farnaby. E. Johnson.

Johnson, though sometimes licentious, was also sometimes even prudish. In taking the sixth and fifth upon the fourth of the scale, his associates accompanied them, in the modern way, with a third; Johnson however refuses this, and, following the strict Roman practice, doubles the bass note instead.

- ↑ It was by a chance more unfortunate even than usual that Dr. Burney selected this Psalter,—on the whole the best that ever appeared,—as a victim to his strange prejudice against our native music. His slighting verdict is that 'the book has no merit, but what was very common at the time it was printed': which is certainly true; but Allison, a musician of the first rank, is not deserving of contempt on the ground that merit of the highest kind happened to be very common in his day.