as possible a quantity derived from the electromagnetic absolute system.

340.] When a material unit representing this abstract quantity has been made, other standards are constructed by copying this unit, a process capable of extreme accuracy—of much greater accuracy than, for instance, the copying of foot-rules from a standard foot.

These copies, made of the most permanent materials, are distributed over all parts of the world, so that it is not likely that any difficulty will be found in obtaining copies of them if the original standards should be lost.

But such units as that of Siemens can without very great labour be reconstructed with considerable accuracy, so that as the relation of the Ohm to Siemens unit is known, the Ohm can be reproduced even without having a standard to copy, though the labour is much greater and the accuracy much less than by the method of copying.

Finally, the Ohm may be reproduced by the electromagnetic method by which it was originally determined. This method, which is considerably more laborious than the determination of a foot from the seconds pendulum, is probably inferior in accuracy to that last mentioned. On the other hand, the determination of the electromagnetic unit in terms of the Ohm with an amount of accuracy corresponding to the progress of electrical science, is a most important physical research and well worthy of being repeated.

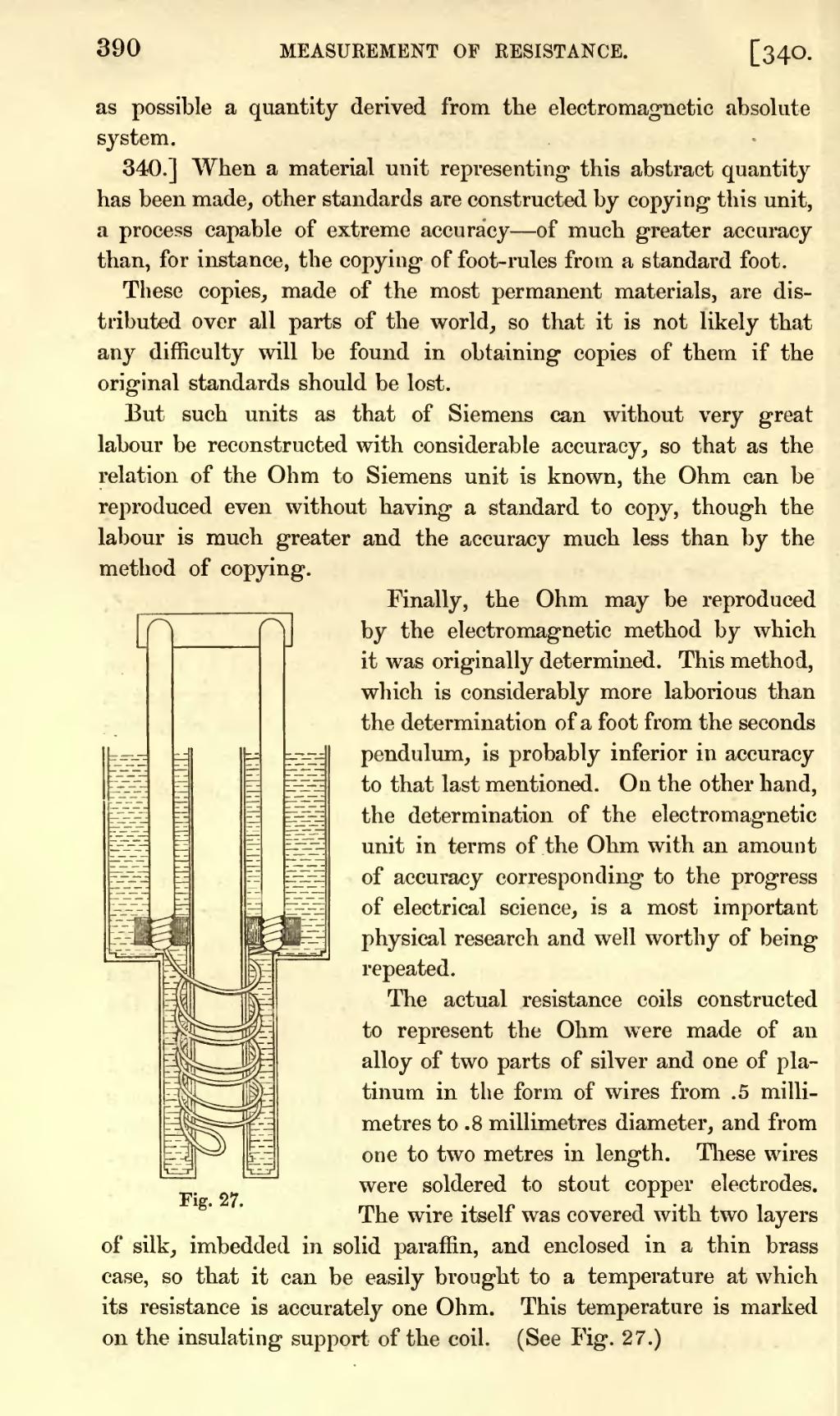

The actual resistance coils constructed to represent the Ohm were made of an alloy of two parts of silver and one of platinum in the form of wires from .5 millimetres to .8 millimetres diameter, and from one to two metres in length. These wires were soldered to stout copper electrodes. The wire itself was covered with two layers of silk, imbedded in solid paraffin, and enclosed in a thin brass case, so that it can be easily brought to a temperature at which its resistance is accurately one Ohm. This temperature is marked on the insulating support of the coil. (See Fig. 27.)