|

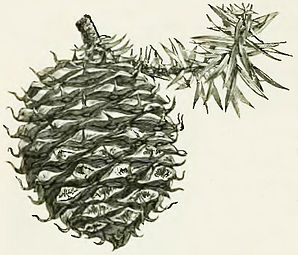

| FIG. 20. |

Perhaps the most remarkable of all the fruits eaten by the natives is the Bunya-bunya. It is obtained from a Queensland pine (Araucaria Bidwilli), which appears to be restricted to a very limited area, and to bear a profusion of fruit only once in about three years. The only tree bearing fruit which I have seen had a bunch of cones near the top, and the stem and leaves being prickly, it was not easy to get at them. One was removed, which is figured here.—(Fig. 20.) The tree was growing in the garden of the late Mr. Hugh Glass, at Moonee Ponds. The length of the cone was six inches, and the diameter five inches and three-quarters; and it weighed shortly after it was pulled two pounds ten ounces. In the native forests much larger fruits are found. The engraving shows the fruit about one-third of the natural size.

When there is a profusion of fruit in the Bunya-bunya district "the supply is vastly larger than can be consumed by the tribes within whose territory the trees are found. Consequently, large numbers of strangers visit the district, some of them coming from very great distances, and all are welcome to consume as much as they desire, for there is enough and to spare, during the few weeks which the season lasts. The fruit is of a richly farinaceous kind, and the blacks quickly fatten upon it. But after a short indulgence in an exclusively vegetable diet, having previously been accustomed to live almost entirely upon animal food, they experience an irresistible longing for flesh. This desire they dare not indulge by killing any of the wild animals of the district—kangaroo, opossum, and bandicoot are alike sacred from their touch, because they are absolutely necessary for the existence of the friendly tribe whose hospitality they are partaking. In this condition, some of the stranger tribes resort to the horrible practice of cannibalism, and sacrifice one of their own number to provide the longed-for feast of flesh. It is not the disgusting cruelty, the frightful inhumanity, or the curious physiological question involved that is now under consideration; but the remarkable fact educed of an unhesitating obedience, under circumstances of extraordinary temptation, to laws arising out of the necessities of their existence; and the indirect proof afforded of the severe pressure upon the supply of food which, under ordinary circumstances, must have prevailed among the Aboriginal tribes. The strangers dared not, in their utmost longing, touch the wild animals, because they were absolutely necessary for the existence of the tribe to which the district belonged. They might eat their fill of the Bunya-bunya, because that was in profusion, and prescription had