usable information.[1] Meanwhile, it had been determined that the States could use a portion of their 1½ percent Federal-aid planning apportionments for participation in the HRCS so long as State matching funds were also provided. The timing of the creation of the HRCS coincided with the initiation of the greatly expanded postwar Federal-aid highway program. This permitted the growth of HRB at a time when it was needed most to keep pace with the needs of the highway program.

In 1962 the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) was established through which a national program of highway research could be developed jointly by the States (through AASHO), the BPR and the HRB, under a plan of pooled financing by the States and BPR. This program came soon after the initiation of the Interstate program when many new problems were beginning to emerge.

Between 1964 and 1967, the HRB initiated an automated Highway Research Information Service (HRIS). Items selected for HRIS processing fell into two general categories, research-in-progress reports and abstracts of published research articles or reports. The program was extended to include foreign research-in-progress and foreign language research reports through cooperative exchange agreements arranged with international organizations and other nations. Presently, from computer storage, HRIS provides abstracts of published works and summaries of ongoing research projects in response to specific inquiries.

A research library was initiated in 1946. Today, it plays a very important role in not only providing the specialized professional library services the TRB requires for its activities, but it also maintains an awareness of the subject content of other libraries and other institutions that may possess material of TRB interest, Copies of all TRB publications are also maintained by the library.

Current Status of the Federal–State Relationship

The unique Federal–State partnership in the Federal-aid highway program still exists despite the constrictions placed upon it by the changing climate in which the highway program must be administered.

When one speaks today about the Federal side of the Federal–State relationship in the administration of the Federal-aid highway program, actually the Federal Highway Administration is no longer the only Federal agency involved. Many other Federal agencies are now legally involved in the program, e.g., the Environmental Protection Agency; the Departments of the Interior, Commerce, Labor, Housing and Urban Development, and Justice; the Occupational Safety and Health Administration; the Office of Economic Opportunity; the Urban Mass Transportation Administration; the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; the Corps of Engineers; and a number of Federal councils, commissions, and boards.

Somewhat the same situation exists when one speaks about the State side of the Federal–State relationship. Many of the provisions of recent Federal (and some State) legislation require the States to coordinate with their local subdivisions and State and regional planning groups and commissions. In some program categories, project initiation is vested with the local subdivisions.

The increasing complexity of Federal highway legislation and other interrelated and interacting Federal legislation obviously have had an inevitable impact on the administration of the Federal-aid program. The early procedures were strikingly simple by comparison with today’s requirements. The problem then was the extensive centralization of final authority at the Federal level in Washington. Over the years this problem was gradually corrected by decentralization, but intricate programs and project processing requirements were substituted by other important, but sometimes conflicting, programs, making accomplishments tediously slow.

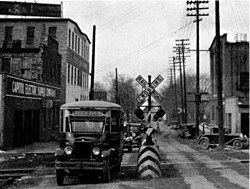

Lansing, Mich., street scene about 1930. Note the brick pavement, railroad warning device and the municipal bus.

Legislative Developments[N 1]

Many additions and changes in the Federal-aid highway program evolved through continuing Federal legislation after 1921. Most of these have increased the effectiveness of the program but have resulted in more complex procedures for administering the program.

During the Depression years larger regular authorizations and special appropriations were made to provide employment opportunities, and special regulations were necessary to insure that this purpose was achieved. For the first time, Federal-aid funds were made available for extensions to the Federal-aid system into and through municipalities and also for secondary feeder roads.

In 1934, 1½ percent of apportioned funds were made eligible for surveys, planning, and engineering investigations. Later this was broadened to include highway research and statewide highway planning surveys. Special funds were provided for the elimination of hazardous railroad grade crossings.

- ↑ This section is a very brief summary of the legislation to identify major trends. Many of these points are discussed in more detail later in this and other chapters.

In 1944 the Federal-aid system was expanded to include a secondary system of farm-to-market roads and an urban program of extensions of primary routes in urban areas of 5,000 population or more. In addition a 40,000-mile National System of Interstate

210

- ↑ Id., pp. 57, 58.