States Government owned practically all of the undeveloped land, the sale of which was its main source of revenue. What could be more logical than to set aside a portion of the revenues from the sale of public lands for building roads and canals, thus, promoting not only the development of the new territories, but land sales as well?

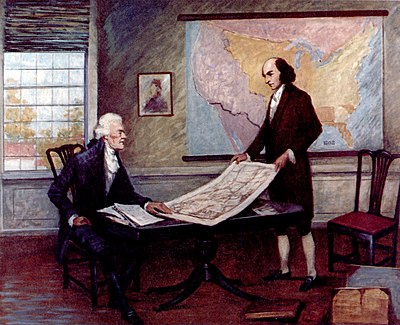

The Gallatin Report.

In 1801 Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, in a letter to Representative William B. Giles of Virginia, suggested that one-tenth of the net proceeds of public land sales be applied to the building of roads, but only with the consent of the States through which such roads might pass.[1] This idea was incorporated in the Ohio Statehood Enabling Act of 1802, except that only 5 percent of the proceeds of land sales was to be set aside for roads. Ohio’s constitutional convention modified the 5-percent plan by insisting that three-fifths of the road money be spent on roads “within” the State and under the control of the Legislature. This change was accepted by Congress in 1803 by an act which established a “2 percent fund” derived from the sale of public lands to be used under the direction of Congress for constructing roads “to and through” Ohio.[2]

Following the Ohio precedent, Louisiana, Indiana, Mississippi, Illinois, Alabama, and Missouri, on their admission to statehood, were given 3 percent grants for roads, canals, levees, river improvements, and schools. Congress later granted an additional 2 percent to these States, except Indiana and Illinois, which, with Ohio, had already received the equivalent in expenditures on the National Road. The additional 2 percent funds were used by these States for railroads.

The remaining 24 States admitted between 1820 and 1910 received 5 percent grants, except Texas and West Virginia, in which the Federal Government had no lands. Of the 22 States that received grants, 9 were authorized to use them for public roads, canals, and internal improvements and 13 for schools.[3]

The First National Transportation Plan

Secretary Gallatin, at the request of the U.S. Senate, made the first national inventory of transportation resources in 1807. Out of this study came his report on roads and canals in 1808, a remarkably comprehensive and forward-looking document which, unfortunately, had little immediate effect on U.S. transportation policy.

17

- ↑ P. D. Jordon, The National Road (Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1948) pp. 71, 72.

- ↑ A. Rose, Historic American Highways—Public Roads of the Past (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1953) p. 66.

- ↑ Office of Federal Coordinator of U.S. Transportation, Public Aids to Transportation, Aids to Railroads and Related Subjects, Vol. II (GPO Washington, D.C., 1938) p. 7.