also published educational articles on the principles of good roadbuilding and the economic benefits of all-weather roads. He used pictures of good and bad roads freely, thus, holding the reader’s attention where words alone would have failed. Newspapers and national magazines reprinted these articles, affording them the widest distribution.[1]

A “Good Roads Association” was formed in Missouri in 1891, followed by similar organizations in other States.[2] A national road conference, the first of its kind, was held in 1894 with representatives from 11 States. Resolutions passed at this conference urged the State legislatures to set up limited systems of State roads, and to create temporary highway commissions to recommend suitable legislation to implement good roads programs.[3]

State Aid Spreads the Financial Burden

In 1890 all the public roads in New Jersey outside of the cities were under township control and were built and maintained at township expense. Purely local traffic predominated on most of these roads, but some carried traffic from neighboring townships and even beyond, and on a few, teams could be counted from as many as 20 townships. By actual count, the New Jersey Road Improvement Association proved that the traffic on these main roads was intercounty rather than local, and it asserted that, in fairness, the counties and the State should shoulder part of the burden of building and maintaining them. The Association and the League of American Wheelmen put their support behind a State-aid bill in the Legislature which became law April 14, 1891. This law declared that “The expense of constructing permanently improved roads may reasonably be imposed, in due proportions, upon the State and upon the counties in which they are located.” It left the initiation, planning and supervision of State-aided projects in the hands of the county officials, but reserved to the State, represented by the Board of Agriculture, the right to approve projects and to accept or reject contracts. Upon completion, the cost of the improvement was to be split three ways: one-tenth to be assessed to the property holders along the road, one-third to the State and the remainder to the county. The act appropriated $75,000 as the State’s share for the first year’s operations.[4]

The State-aid act was challenged in the courts and upheld. The Board then approved petitions for State aid to three projects in Middlesex County totaling 10.55 miles which, when completed in December 1892, became the first roads to be improved under the act.[5]

In 1894 the operation of the act was placed under a Commissioner of Public Roads appointed by the Governor for a 3-year term. New Jersey, thus, became the second State, after Massachusetts, to establish a State highway organization. For a number of years, however, the Commissioner of Public Roads had very little real authority over State-aided roads and none at all over other roads. Lacking the power to initiate projects, he could not insure that State-aided roads would link up into highways of any great continuous length, and after they were completed, he could not require that they be adequately maintained.

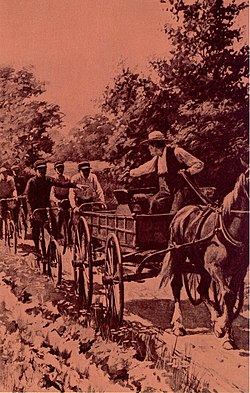

“The Right-of-Way”—bicyclists and horsecart vying for the road.

Nevertheless, the New Jersey State-Aid Act was a milestone in the history of highway administration in the United States, for it clearly stated the principle that highway improvement for the general good was an obligation of the State and county, as well as the people living along the highway. The act also imposed much-needed reforms in local road administration: it abolished the numerous road districts, along with the overseer method of road improvement, and required the township committees to adopt a systematic plan for improving the highways.

The First State Highway Department

Massachusetts approach State aid somewhat differently from New Jersey. The Legislature created a 3-man continuing commission and charged it with the building and control of a system of main highways connecting the municipalities of the Commonwealth. Originally, the counties were supposed to grade these roads, after which the Highway Commission would surface them. In 1894, the law was changed to require the Commission to shoulder the entire cost of construction, charging one-quarter of the expense back to the counties.[6] At the same time, the Legislature appropriated $300,000 to begin the operation of the Commonwealth Highway Plan, an amount that was afterward substantially increased from year to year.

48

- ↑ Id., p. 129.

- ↑ W. H. Moore, Response to Address of Welcome, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) p. 12.

- ↑ H. Trumbower, supra, note 20, p. 407.

- ↑ L. Page, Progress and Present Status of the Good Roads Movement in the United States, Yearbook of The Department of Agriculture, 1910 (GPO, Washington, D.C., 1911) p. 270.

- ↑ A. Rose, Historic American Highways—Public Roads of the Past (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1953) pp. 94, 95.

- ↑ G. Chatburn, supra, note 21, pp. 150, 151.