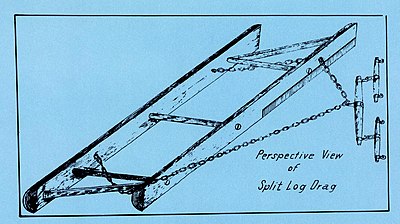

apart by struts and the lower edge of the front log was shod with a ¼-inch steel cutting plate. A hitching chain attached to the front log could be adjusted so that the drag would move earth to either side of the road as the device was pulled behind a team. This drag could be made on the farm for about $2.[1]

The King split-log drag was a surprisingly effective maintenance machine. After a little instruction and practice, an average farmer could easily drag 6 to 8 miles of road per day and could keep a well-graded dirt road in good shape for light traffic for as little as $8 per mile per year. The appearance of the King drag coincided with Director Page’s decision to place greater emphasis on earth and sand-clay roads in the object lesson road program, so Page decided to promote dragging as well. In 1906 he had King write a manual on how to make and use the split-log drag. This was published by the Department of Agriculture as a Farmer’s Bulletin, and thousands of copies were distributed. The OPR assigned experts to deliver lectures and make demonstrations in the use of the drag. A number of States passed “King Drag Laws” authorizing the township supervisors to contract with abutting farmers to drag the public roads.[2]

This activity, in a few years, brought about a remarkable improvement in the condition of the country dirt roads and brought home to the local supervisors, as nothing else had before, the importance of prompt and intelligent maintenance.

Experimental Maintenance

In 1911 the French roads were not only the best in the world, but were also the best maintained. Maintenance was strongly centralized and closely supervised; every road was divided into short segments of a few kilometers, each the full-time responsibility of a paid patrolman who lived nearby, usually within walking distance. Page wanted to try out the French system under American conditions, and in 1911 at his recommendation, the Secretary of Agriculture contracted with Alexandria County, Virginia, for a 2-year experimental maintenance project to include 8 miles of earth roads. Under this contract, the county supervisors agreed to shape up the roads and put them in good condition, after which the OPR hired a local farmer as a patrolman to maintain the roads under OPR supervision. The patrolman was paid $60 per month plus an extra $1 per day whenever he used his team for dragging.

The roads selected for the experiment—Columbia Pike and the Mount Vernon Road—were among the heaviest-traveled in the county,[N 1] yet the patrolman kept them in first-class condition most of the time at a cost of $95.77 per mile per year.[3] This, however, was far more than the average rural county was spending to maintain its roads. In the final analysis, this experiment demonstrated not so much the efficiency of the patrol system as the desirability of more durable surfaces for all but the very lightest-trafficked roads.

- ↑ One section near Fort Myer carried 173 wagons and 96 cavalry horses per day, plus a few runabouts.

The Washington-Atlanta Maintenance Demonstration Road

The Alexandria County experiment was the beginning of a major effort by the OPR to raise maintenance standards in the counties. By 1912, a decade of promotion by the good roads associations, the motorists, and the Office of Public Roads and others had trebled the funds available annually for roadbuilding. Hundreds of counties had issued bonds to finance road

72