ways shown in Figs. 6, 7, and 8. If we take any single colour, it may obviously be applied in only 1 way. But four colours may be

An image should appear at this position in the text. To use the entire page scan as a placeholder, edit this page and replace "{{missing image}}" with "{{raw image|Amusements in mathematics.djvu/221}}". Otherwise, if you are able to provide the image then please do so. For guidance, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images. |

selected in 35 ways out of seven; three in 35 ways; two in 21 ways; and one colour in 7 ways. Therefore 35 applied in 2 ways = 70; 35 in 3 ways = 105; 21 in 3 ways = 63; and 7 in 1 way = 7. Consequently the pyramid may be painted in 245 different ways (70 + 105 + 63 + 7), using the seven colours of the solar spectrum in accordance with the conditions of the puzzle.

282.—THE ANTIQUARY'S CHAIN.

An image should appear at this position in the text. To use the entire page scan as a placeholder, edit this page and replace "{{missing image}}" with "{{raw image|Amusements in mathematics.djvu/221}}". Otherwise, if you are able to provide the image then please do so. For guidance, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images. |

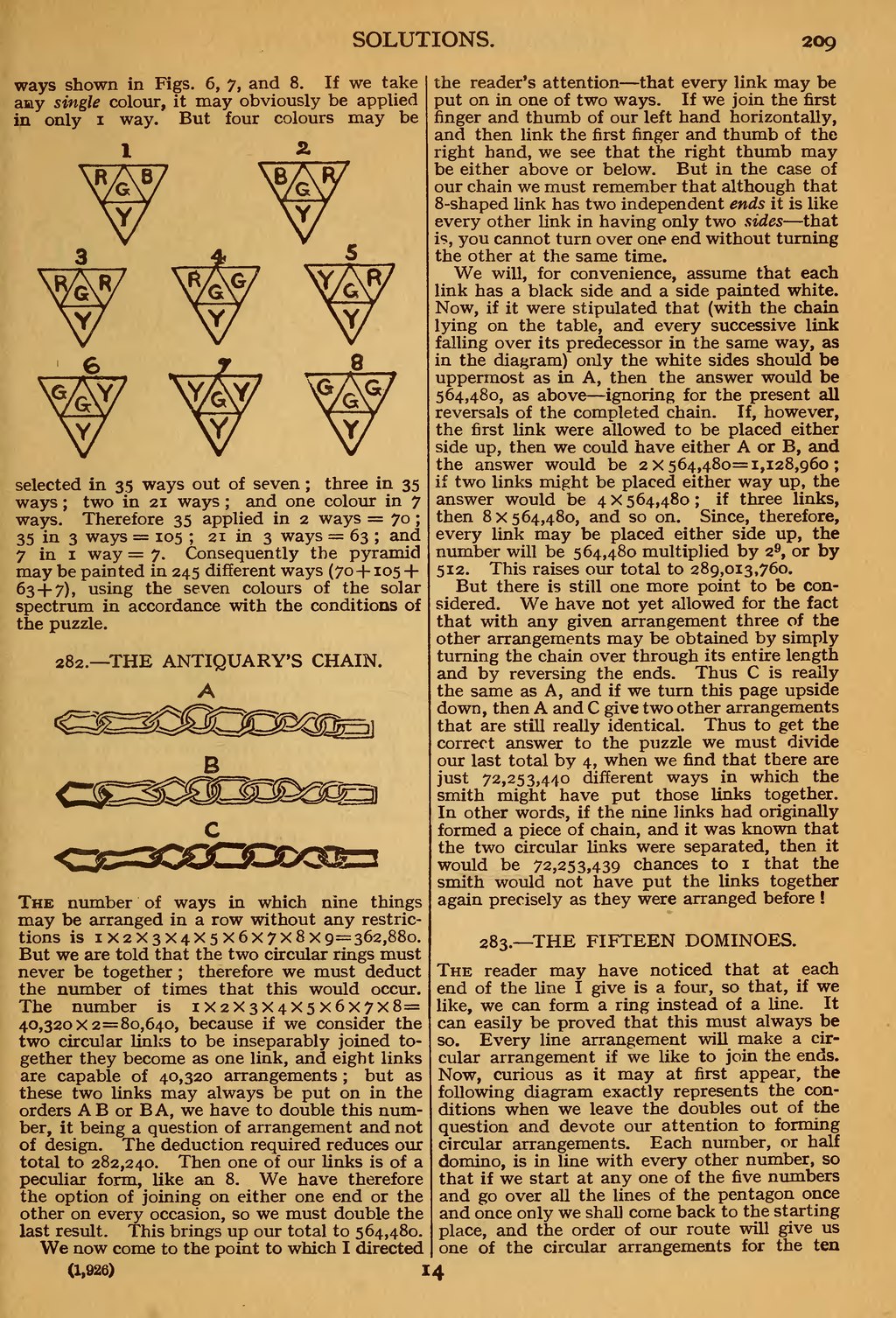

The number of ways in which nine things may be arranged in a row without any restrictions is 1×2×3×4×5×6×7×8×9=362,880. But we are told that the two circular rings must never be together; therefore we must deduct the number of times that this would occur. The number is 1×2×3×4×5×6×7×8=40,320×2=80,640, because if we consider the two circular links to be inseparably joined together they become as one link, and eight links are capable of 40,320 arrangements; but as these two links may always be put on in the orders A B or B A, we have to double this number, it being a question of arrangement and not of design. The deduction required reduces our total to 282,240. Then one of our links is of a peculiar form, like an 8. We have therefore the option of joining on either one end or the other on every occasion, so we must double the last result. This brings up our total to 564,480.

We now come to the point to which I directed the reader's attention—that every link may be put on in one of two ways. If we join the first finger and thumb of our left hand horizontally, and then link the first finger and thumb of the right hand, we see that the right thumb may be either above or below. But in the case of our chain we must remember that although that 8-shaped link has two independent ends it is like every other link in having only two sides—that is, you cannot turn over one end without turning the other at the same time.

We will, for convenience, assume that each link has a black side and a side painted white. Now, if it were stipulated that (with the chain lying on the table, and every successive link falling over its predecessor in the same way, as in the diagram) only the white sides should be uppermost as in A, then the answer would be 564,480, as above—ignoring for the present all reversals of the completed chain. If, however, the first link were allowed to be placed either side up, then we could have either A or B, and the answer would be ×564,480=1,128,960; if two links might be placed either way up, the answer would be 4×564,480; if three links, then 8×564,480, and so on. Since, therefore, every link may be placed either side up, the number will be 564,480 multiplied by 29, or by 512. This raises our total to 289,013,760.

But there is still one more point to be considered. We have not yet allowed for the fact that with any given arrangement three of the other arrangements may be obtained by simply turning the chain over through its entire length and by reversing the ends. Thus C is really the same as A, and if we turn this page upside down, then A and C give two other arrangements that are still really identical. Thus to get the correct answer to the puzzle we must divide our last total by 4, when we find that there are just 72,253,440 different ways in which the smith might have put those links together. In other words, if the nine links had originally formed a piece of chain, and it was known that the two circular Links were separated, then it would be 72,253,439 chances to 1 that the smith would not have put the links together again precisely as they were arranged before!

283.—THE FIFTEEN DOMINOES.

The reader may have noticed that at each end of the line I give is a four, so that, if we like, we can form a ring instead of a line. It can easily be proved that this must always be so. Every line arrangement will make a circular arrangement if we like to join the ends. Now, curious as it may at first appear, the following diagram exactly represents the conditions when we leave the doubles out of the question and devote our attention to forming circular arrangements. Each number, or half domino, is in line with every other number, so that if we start at any one of the five numbers and go over all the lines of the pentagon once and once only we shall come back to the starting place, and the order of our route will give us one of the circular arrangements for the ten