versant with those authorities, it might appear that the edifices were identical. But it is well known that the term "domus" was applied to various structures, generally, with the exception of the keep, of an unsubstantial character, raised within the enceinte of a medieval fortress, often mere penthouses of wood and plaster, always in need of repair.

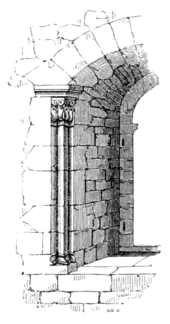

The preceding observations may possibly induce local antiquaries to pursue still further the history of this ancient building, the identification of which is thus attempted, and it is hoped they may also contribute to its preservation as an interesting relic of early times. The few architectural features it now offers, belong to the latter part of the twelfth century, and of these the most prominent is a window in a tolerably perfect state; it has a segmental arch and a drip-stone over it, with the usual Norman abacus moulding at the imposts; this is continued as a string along the wall, though broken in places by later insertions. Interiorly it is ornamented with shafts in the jambs, sunk in a square recess in the angle, having capitals sculptured with foliage of a peculiar but late Norman character; the bases approaching to Early English. This window is altogether remarkable and of an unusual design. It is now closed by wooden shutters, and in all likelihood was never glazed.

The peculiar construction of the west wall of Southampton is familiar to antiquaries; an accurate measurement of the arches was taken by Sir Henry Englefield in 1801[1]; and the reader may be referred to his essay for a minute description

- ↑ "A Walk through Southampton," 4to. 1801. p. 23.