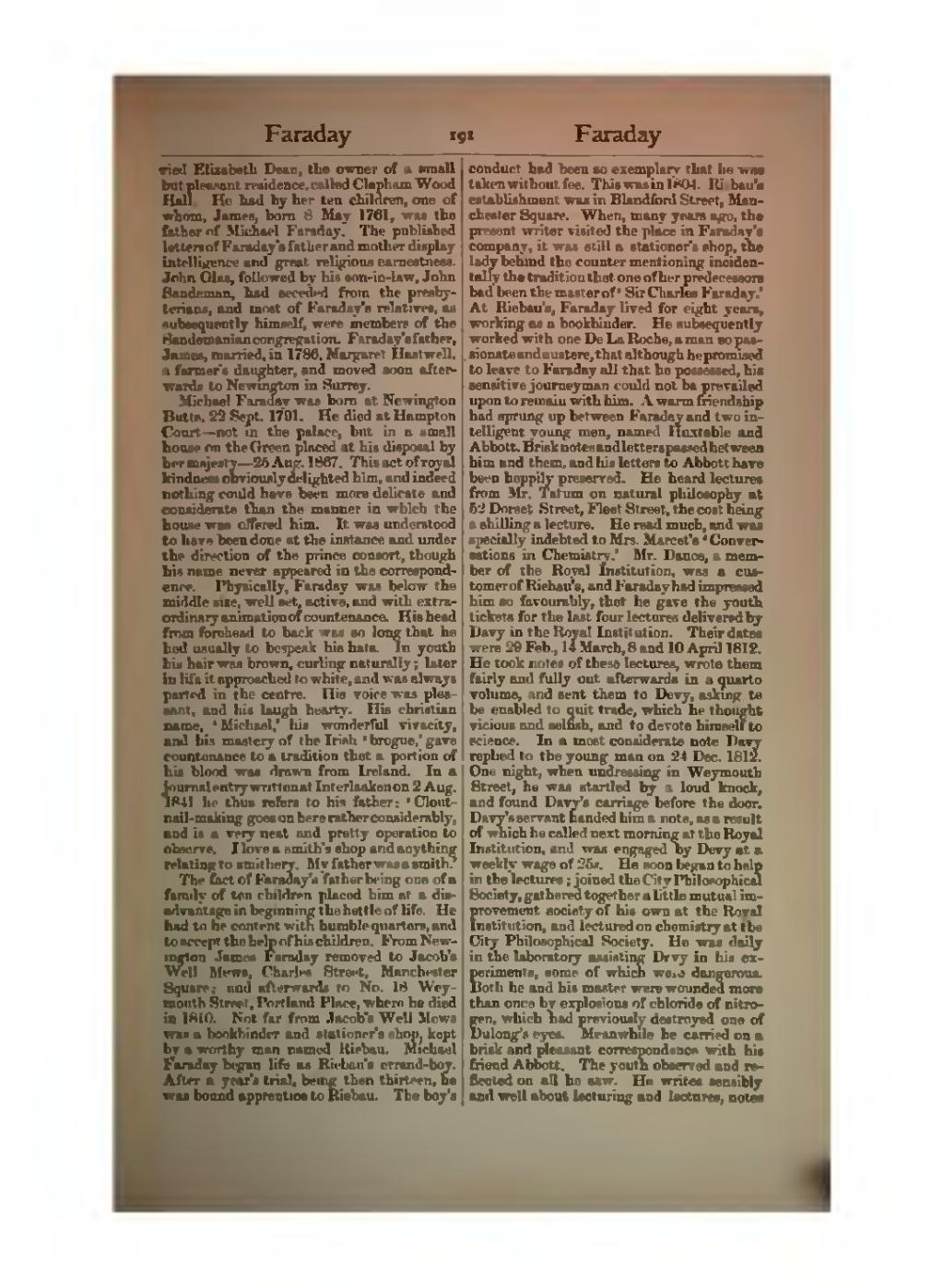

ried Elizabeth Dean, the owner of a small but pleasant residence, called Clapham Wood Hall. He had by her ten children, one of whom, James, born 8 May 1761, was the father of Michael Faraday. The published letters of Faraday's father and mother display intelligence and great religious earnestness. John Glas, followed by his son-in-law, John Sandeman, had seceded from the presbyterians, and most of Faraday's relatives, as subsequently himself, were members of the Sandemanian congregation. Faraday's father, James, married, in 1786, Margaret Hastwell, a farmer's daughter, and moved soon afterwards to Newington in Surrey.

Michael Faraday was horn at Newington Butts, 22 Sept. 1791. He died at Hampton Court — not in the palace, but in a small house on the Green placed at his disposal by her majesty — 25 Aug. 1867. This act of royal kindness obviously delighted him, and indeed nothing could have been more delicate and considerate than the manner in which the house was offered him. It was understood to have been done at the instance and under the direction of the prince consort, though his name never appeared in the correspondence. Physically, Faraday was below the middle size, well set, active, and with extraordinary animation of countenance. His head from forehead to back was so long that he had usually to bespeak his hats. In youth his hair brown, curling naturally; later in life it approached to white, and was always parted in the centre. His voice was pleasant, and his laugh hearty. His christian name, 'Michael,' his wonderful vivacity, and his mastery of the Irish 'brogue,' gave countenance to a tradition that a portion of his blood was drawn from Ireland. In a journal entry written at Interlaaken on 2 Aug. 1841 he thus refers to his father: 'Cloutnail-making goes on here rather considerably, and is a very neat and pretty operation to observe. I love a smith's shop and anything relating to smithery. My father was a smith.'

The fact of Faraday's father being one of a family of ten children placed him at a disadvantage in beginning the battle of life. He had to be content with humble quarters and to accept the help of his children. From Newington James Faraday removed to Jacob's Well Mews, Charles Street, Manchester Square; and afterwards to No. 18 Weymouth Street, Portland Place, where he died in 1810. Not far from Jacob's Well Mews was a bookbinder and stationer's shop kept by a worthy man named Riebau, Michael Faraday began life as Riebau's errand-boy. After a year's trial, being then thirteen, he was bound apprentice to Riebau. The boy's conduct had been so exemplary that he was taken without fee. This was in 1804, Riebau's establishment was in Blandford Street, Manchester Square. When, many years ago, the present writer visited the place in Faraday's company, it was still a stationer's shop, the lady behind the counter mentioning incidentally that one of her predecessors had been master of 'Sir Charles Faraday,' At Riebau's, Faraday lived for eight years, working as a bookbinder. He subsequently worked with one De La Roche, a man so passionate and austere, that although he promised to leave to Faraday all that he possessed, his sensitive journeyman could not be prevailed upon to remain with him. A warm friendship had sprung up between Faraday and two intelligent young men, named Huxtable and Abbott, Brisk notes and letters passed between him and them, and his letters to Abbott have been happily preserved. He heard lectures from Mr. Tatum on natural philosophy at 52 Dorset Street, Fleet Street, the cost being a shilling a lecture. He read much, and was specially indebted to Mrs. Marcet's 'Conversations in Chemistry.' Mr. Dance, a member of the Royal Institution, was a customer of Riebau's, and Faraday had impressed him so favourably, that he gave the youth tickets for the last four lectures delivered by Davy in the Royal Institution. Their dates were 29 Feb., 14 March, 8 and 10 April 1812. He took notes of these lectures, wrote them fairly and fully out afterwards in a quarto volume, and sent them to Davy, asking to be enabled to quit trade, which he thought vicious and selfish, and to devote himself to science. In a most considerate note Davy replied to the young man on 24 Dec. 1812. One night, when undressing in Weymouth Street, be was startled by a loud knock, and found Davy's carriage before the door. Davy's servant handed him a note, as a result of which he called next morning at the Royal Institution, and was engaged by Devy at a weekly wage of 25s. He soon began to help in the lectures; joined the City Philosophical Society, gathered together a little mutual improvement society of his own at the Royal Institution, and lectured on chemistry at the City Philosophical Society. He was daily in the laboratory assisting Davy in his experiments, some of which were dangerous. Both he and his master were wounded more than once by explosions of chloride of nitrogen, which had previously destroyed one of Dulong's eyes. Meanwhile he carried on a brisk and pleasant correspondence with his friend Abbott. The youth observed and reflected on all he saw. He writes sensibly and well about lecturing and lectures, notes