ANDALUSIA, or Andalucia, a captaincy-general, and formerly a province, of southern Spain; bounded on the N. by Estremadura and New Castile, E. by Murcia and the Mediterranean Sea, S. by the Mediterranean and Atlantic, and W. by Portugal. Pop. (1900) 3,563,606; area, 33,777 sq. m. Andalusia was divided in 1833 into the eight provinces of Almería, Cadiz, Cordova, Granada, Jaén, Huelva, Malaga and Seville, which are described in separate articles. Its ancient name, though no longer used officially, except to designate a military district, has not been superseded in popular speech by the names of the eight modern divisions.

Andalusia consists of a great plain, the valley of the Guadalquivir, shut in by mountain ranges on every side except the S.W., where it descends to the Atlantic. This lowland, which is known as Andalucia Baja, or Lower Andalusia, resembles the valley of the Ebro in its slight elevation above sea-level (300-400 ft.), and in the number of brackish lakes or fens, and waste lands (despoblados) impregnated with salt, which seem to indicate that the whole surface was covered by the sea at no distant geological date. The barren tracts are, however, exceptional and a far larger area is richly fertile. Some districts, indeed, such as the Vega of Granada, are famous for the luxuriance of their vegetation. The Guadalquivir (q.v.) rises among the mountains of Jaén and flows in a south-westerly direction to the Gulf of Cadiz, receiving many considerable tributaries on its way. On the north, its valley is bounded by the wild Sierra Morena; on the south, by the mountains of the Mediterranean littoral, among which the Sierra Nevada (q.v.), with its peaks of Mulhacen (11,421 ft.) and Veleta (11,148 ft.), is the most conspicuous. These highlands, with the mountains of Jaén and Almería on the east, constitute Andalucia Alta or Upper Andalusia.

No part of Spain has greater natural riches. The sherry produced near Jeréz de la Frontera, the copper of the Rio Tinto mines and the lead of Almería are famous. But the most noteworthy characteristics of the province are, perhaps, the brilliancy of its climate, the beauty of its scenery (which ranges in character from the alpine to the tropical), and the interest of its art and antiquities. The climate necessarily varies widely with the altitude. Some of the higher mountains are covered with perpetual snow, a luxury which is highly prized by the inhabitants of the valleys, where the summer is usually extremely hot, and in winter the snow falls only to melt when it reaches the ground. Here the more common European plants and trees give place to the wild olive, the caper bush, the aloe, the cactus, the evergreen oak, the orange, the lemon, the palm and other productions of a tropical climate. On the coasts of the Mediterranean about Marbella and Malaga, the sugar-cane is successfully cultivated. Silk is produced in the same region. Agriculture is in a very backward state and the implements used are most primitive. The chief towns are Seville (pop. 1900, 148,315), which may be regarded as the capital, Malaga (130,109), Granada (75,900), Cadiz (69,382), Jeréz de la Frontera (63,473), Cordova (58,275) and Almería (47,326).

Andalusia has never been, like Castile or Aragon, a separate kingdom. Its history is largely a record of commercial and artistic development. The Guadalquivir valley is often, in part at least, identified with the biblical Tarshish and the classical Tartessus, a famous Phoenician mart. The port of Agadir or Gaddir, now Cadiz, was founded as early as 1100 B.C. Later Carthaginian invaders came from their advanced settlements in the Balearic Islands, about 516 B.C. Greek merchants also visited the coasts. The products of the interior were conveyed by the native Iberians to the maritime colonies, such as Abdera (Adra), Calpe (Gibraltar) or Malaca (Malaga), founded by the foreign merchants. The Punic wars transferred the supreme power from Carthage to Rome, and Latin civilization was established firmly when, in 27 B.C., Andalusia became the Roman province of Baetica—so called after its great waterway, the Baetis (Guadalquivir). In the 5th century the province was overrun by successive invaders—Vandals, Suevi and Visigoths—from the first of whom it may possibly derive its name. The forms Vandalusia and Vandalitia are undoubtedly ancient; many authorities, however, maintain that the name is derived from the Moorish Andalus or Andalosh, “Land of the West”. The Moors first entered the province in 711, and only in 1492 was their power finally broken by the capture of Granada. Their four Andalusian kingdoms, Seville, Jaén, Cordova and Granada, developed a civilization unsurpassed at the time in Europe. An extensive literature, scientific, philosophical and historical, with four world-famous buildings—the Giralda and Alcázar of Seville, the Mezquita or cathedral of Cordova and the Alhambra at Granada—are its chief monuments. In the 16th and 17th centuries, painting replaced architecture as the distinctive art of Andalusia; and many of the foremost Spanish painters, including Velazquez and Murillo, were natives of this province.

Centuries of alien domination have left their mark upon the character and appearance of the Andalusians, a mixed race, who contrast strongly with the true Spaniards and possess many oriental traits. It is impossible to estimate the influence of the elder conquerors, Greek, Carthaginian and Roman; but there are clear traces of Moorish blood, with a less well-defined Jewish and gipsy strain. The men are tall, handsome and well-made, and the women are among the most beautiful in Spain; while the dark complexion and hair of both sexes, and their peculiar dialect of Spanish, so distasteful to pure Castilians, are indisputable evidence of Moorish descent. Their music, dances and many customs, come from the East. In general, the people are lively, good-humoured and ready-witted, fond of pleasure, lazy and extremely superstitious. In the literature and drama of his country, the Andalusian is traditionally represented as the Gascon of Spain, ever boastful and mercurial; or else as a picaresque hero, bull-fighter, brigand or smuggler. Andalusia is still famous for its bull-fighters; and every outlying hamlet has its legends of highwaymen and contraband.

In addition to the numerous works cited under the heading Spain, see Curiosidades historicas de Andalucia, by N. Diáz de Escovar (Malaga, 1900); Histoire de la conquête de l’Andalousie, by O. Houdas (Paris, 1889); Andalousie et Portugal (Paris, 1886); El. Folk-Lore Andaluz (Seville, 1883); and Nobleza de Andalucia, by G. Argote de Molina (Seville, 1588).

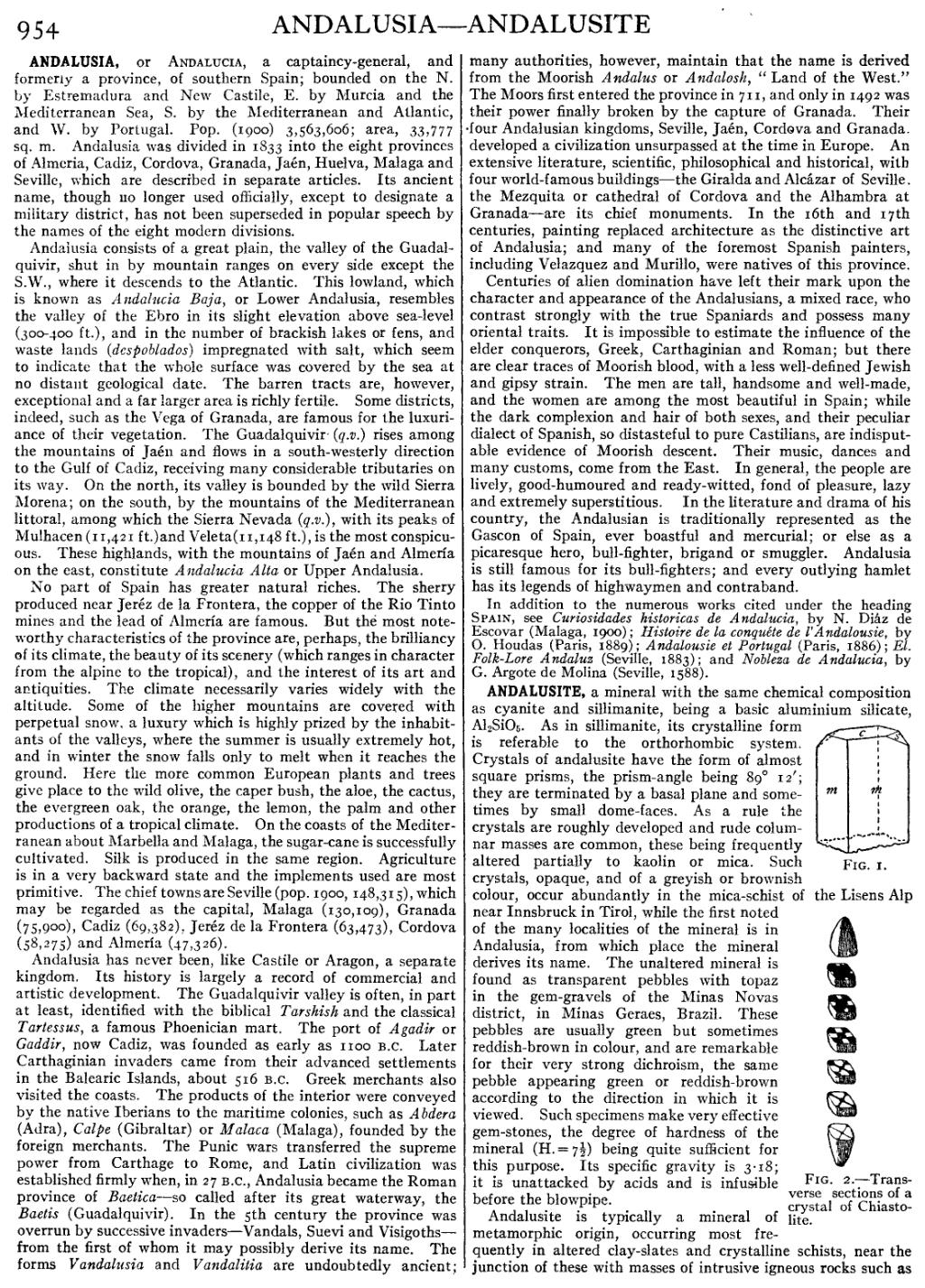

ANDALUSITE, a mineral with the same chemical composition as cyanite and sillimanite, being a basic aluminium silicate, Al2SiO5. As in sillimanite, its crystalline form is referable to the orthorhombic system.

Crystals of andalusite have the form of almost

Fig. 1.square prisms, the prism-angle being 89° 12′; they are terminated by a basal plane and sometimes by small dome-faces. As a rule the crystals are roughly developed and rude columnar masses are common, these being frequently altered partially to kaolin or mica. Such crystals, opaque, and of a greyish or brownish colour, occur abundantly in the mica-schist of the Lisens Alp near Innsbruck in Tirol, while the first noted of the many localities of the mineral is in Andalusia, from which place the mineral derives its name. The unaltered mineral is found as transparent pebbles with topaz in the gem-gravels of the Minas Novas district, in Minas Geraes, Brazil. These pebbles are usually green but sometimes reddish-brown in colour, and are remarkable for their very strong dichroism, the same pebble appearing green or reddish-brown according to the direction in which it is viewed. Such specimens make very effective gem-stones, the degree of hardness of the mineral (H.=71/2) being quite sufficient for this purpose. Its specific gravity is 3·18; it is unattacked by acids and is infusible before the blowpipe.

|

| Fig. 2.—Trans- verse sections of a crystal of Chiastolite. |

Andalusite is typically a mineral of metamorphic origin, occurring most frequently in altered clay-slates and crystalline schists, near the junction of these with masses of intrusive igneous rocks such as