Red Sea. In 1507 Matthew, or Matheus, an Armenian, had been sent as Abyssinian envoy to Portugal to ask aid against the Mussulmans, and in 1520 an embassy under Dom Rodrigo de Lima landed in Abyssinia. An interesting account of this mission, which remained for several years, was written by Francisco Alvarez, the chaplain. Later, Ignatius Loyola wished to essay the task of conversion, but was forbidden. Instead, the pope sent out Joāo Nunez Barreto as patriarch of the East Indies, with Andre de Oviedo as bishop; and from Goa envoys went to Abyssinia, followed by Oviedo himself, to secure the king’s adherence to Rome. After repeated failures some measure of success was achieved, but not till 1604 did the king make formal submission to the pope. Then the people rebelled and the king was slain. Fresh Jesuit victories were followed sooner or later by fresh revolt, and Roman rule hardly triumphed when once for all it was overthrown. In 1633 the Jesuits were expelled and allegiance to Alexandria resumed.

There are many early rock-cut churches in Abyssinia, closely resembling the Coptic. After these, two main types of architecture are found—one basilican, the other native. The cathedral at Axum is basilican, though the early basilicas are nearly all in ruins—e.g. that at Adulis and that of Martula Mariam in Gojam, rebuilt in the 16th century on the ancient foundations. These examples show the influence of those architects who, in the 6th century, built the splendid basilicas at Sanaa and elsewhere in Arabia. Of native churches there are two forms—one square or oblong, found in Tigré; the other circular, found in Amhara and Shoa. In both, the sanctuary is square and stands clear in the centre. An outer court, circular or rectangular, surrounds the body of the church. The square type may be due to basilican influence, the circular is a mere adaptation of the native hut: in both, the arrangements are obviously based on Jewish tradition. Church and outer court are usually thatched, with wattled or mud-built walls adorned with rude frescoes. The altar is a board on four wooden pillars having upon it a small slab (tabūt) of alabaster, marble, or shittim wood, which forms its essential part. At Martula Mariam, the wooden altar overlaid with gold had two slabs of solid gold, one 500, the other 800 ounces in weight. The ark kept at Axum is described as 2 feet high, covered with gold and gems. The liturgy was celebrated on it in the king’s palace at Christmas, Epiphany, Easter and Feast of the Cross.

Generally the Abyssinians agree with the Copts in ritual and practice. The LXX. version was translated into Geez, the literary language, which is used for all services, though hardly understood. Saints and angels are highly revered, if not adored, but graven images are forbidden. Fasts are long and rigid. Confession and absolution, strictly enforced, give great power to the priesthood. The clergy must marry, but once only. Pilgrimage to Jerusalem is a religious duty and covers many sins.

Authorities.—Tellez, Historia de Ethiopia (Coimbra, 1660); Alvarez, translated and edited for the Hakluyt Soc. by Lord Stanley of Alderley, under the title Narrative of the Portuguese Embassy to Abyssinia (London, 1881); Ludolphus, History of Ethiopia (London, 1684, and other works); T. Wright, Christianity of Arabia (London, 1855); C. T. Beke, “Christianity among the Gallas,” Brit. Mag. (London, 1847); J. C. Hotten, Abyssinia Described (London, 1868); “Abyssinian Church Architecture,” Royal Inst. Brit. Arch. Transactions, 1869; Ibid. Journal, March 1897; Archaeologia, vol. xxxii.; J. A. de Graça Barreto, Documenta historiam ecclesiae Habessinarum illustrantia (Olivipone, 1879); E. F. Kromrei, Glaubenslehre und Gebräuche der älteren Abessinischen Kirche (Leipzig, 1895); F. M. E. Pereira, Vida do Abba Samuel (Lisbon, 1894); Idem, Vida do Abba Daniel (Lisbon, 1897); Idem, Historia dos Martyres de Nagran (Lisbon, 1899); Idem, Chronica de Susenyos (Lisbon, text 1892, tr. and notes 1900); Idem, Martyrio de Abba Isaac (Coimbra, 1903); Idem, Vida de S. Paulo de Thebas (Coimbra, 1904); Archdeacon Dowling, The Abyssinian Church, (London, 1909); and periodicals as under Coptic Church. (A. J. B.)

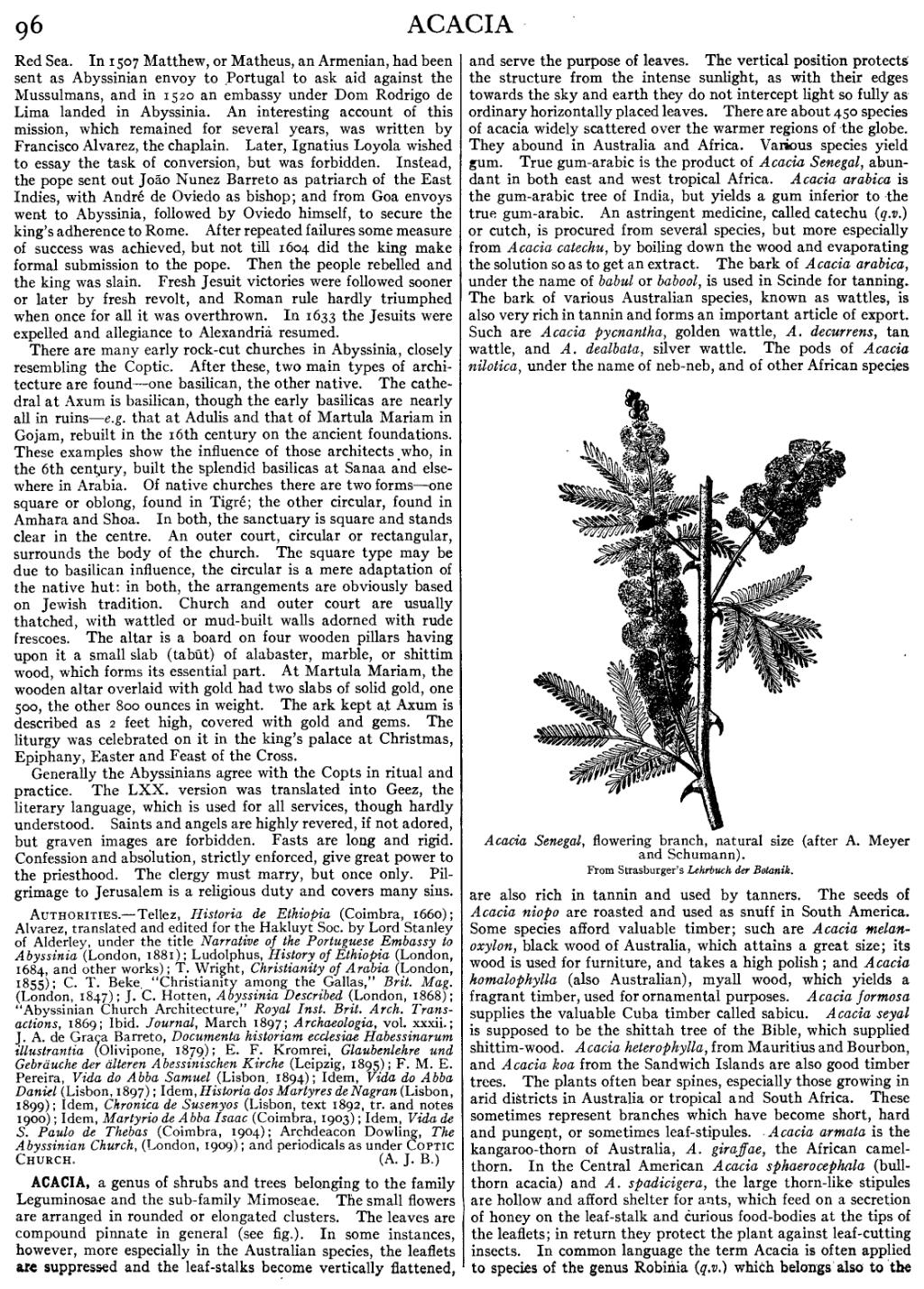

ACACIA, a genus of shrubs and trees belonging to the family Leguminosae and the sub-family Mimoseae. The small flowers are arranged in rounded or elongated clusters. The leaves are compound pinnate in general (see fig.). In some instances, however, more especially in the Australian species, the leaflets are suppressed and the leaf-stalks become vertically flattened, and serve the purpose of leaves. The vertical position protects the structure from the intense sunlight, as with their edges towards the sky and earth they do not intercept light so fully as ordinary horizontally placed leaves. There are about 450 species of acacia widely scattered over the warmer regions of the globe. They abound in Australia and Africa. Various species yield gum. True gum-arabic is the product of Acacia Senegal, abundant in both east and west tropical Africa. Acacia arabica is the gum-arabic tree of India, but yields a gum inferior to the true gum-arabic. An astringent medicine, called catechu (q.v.) or cutch, is procured from several species, but more especially from Acacia catechu, by boiling down the wood and evaporating the solution so as to get an extract. The bark of Acacia arabica, under the name of babul or babool, is used in Scinde for tanning. The bark of various Australian species, known as wattles, is also very rich in tannin and forms an important article of export. Such are Acacia pycnantha, golden wattle, A. decurrens, tan wattle, and A. dealbata, silver wattle.

|

Acacia Senegal, flowering branch, natural size (after A. Meyer |

| From Strasburger’s Lehrbuch der Botanik. |

The pods of Acacia nilotica, under the name of neb-neb, and of other African species are also rich in tannin and used by tanners. The seeds of Acacia niopo are roasted and used as snuff in South America. Some species afford valuable timber; such are Acacia melanoxylon, black wood of Australia, which attains a great size; its wood is used for furniture, and takes a high polish; and Acacia homalophylla (also Australian), myall wood, which yields a fragrant timber, used for ornamental purposes. Acacia formosa supplies the valuable Cuba timber called sabicu. Acacia seyal is supposed to be the shittah tree of the Bible, which supplied shittim-wood. Acacia heterophylla, from Mauritius and Bourbon, and Acacia koa from the Sandwich Islands are also good timber trees. The plants often bear spines, especially those growing in arid districts in Australia or tropical and South Africa. These sometimes represent branches which have become short, hard and pungent, or sometimes leaf-stipules. Acacia armata is the kangaroo-thorn of Australia, A. giraffae, the African camel-thorn. In the Central American Acacia sphaerocephala (bull-thorn acacia) and A. spadicigera, the large thorn-like stipules are hollow and afford shelter for ants, which feed on a secretion of honey on the leaf-stalk and curious food-bodies at the tips of the leaflets; in return they protect the plant against leaf-cutting insects. In common language the term Acacia is often applied to species of the genus Robinia (q.v.) which belongs also to the