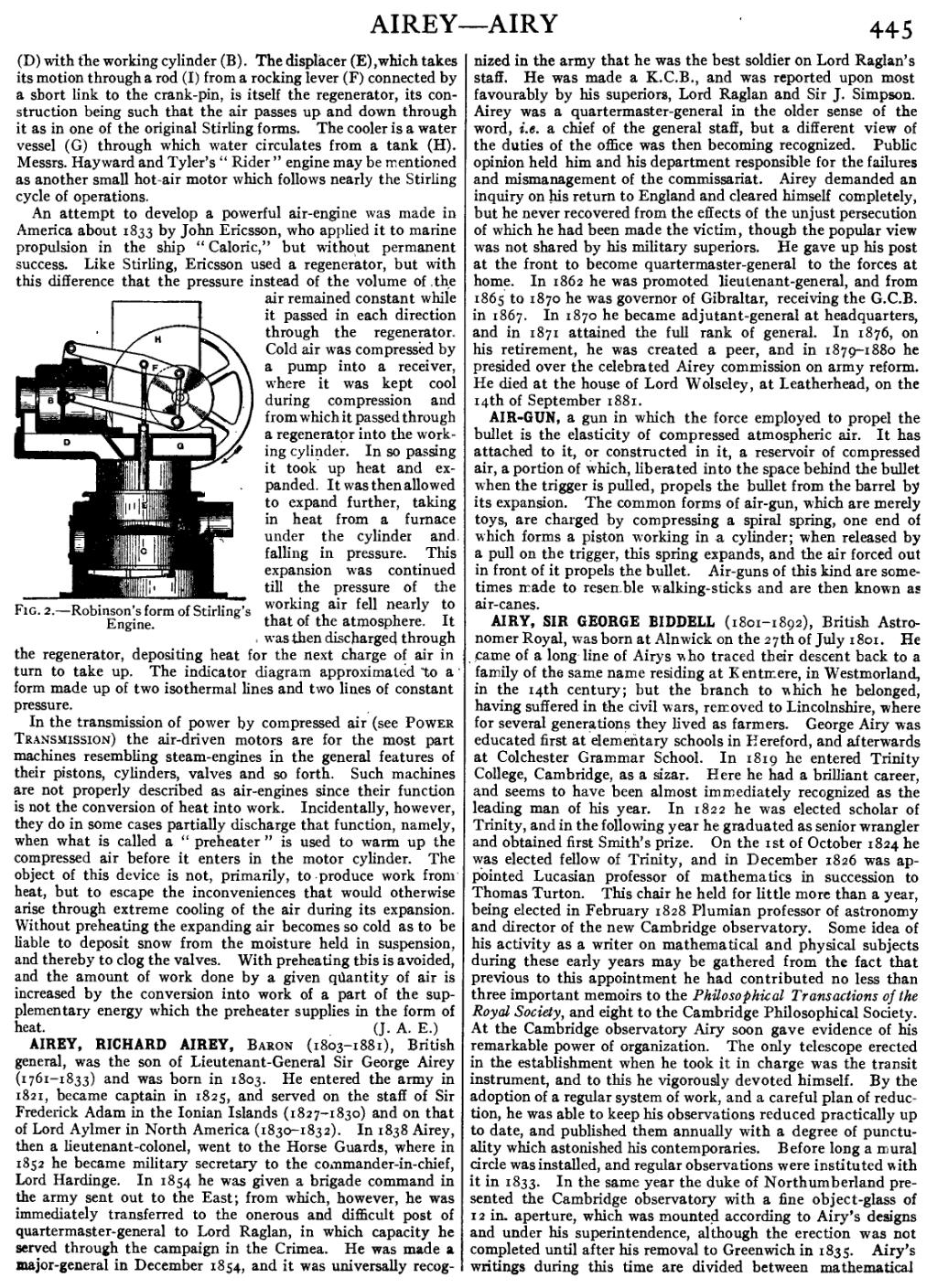

(D) with the working cylinder (B). The displacer (E), which takes its motion through a rod (I) from a rocking lever (F) connected by a short link to the crank-pin, is itself the regenerator, its construction being such that the air passes up and down through it as in one of the original Stirling forms. The cooler is a water vessel (G) through which water circulates from a tank (H). Messrs. Hayward and Tyler’s “Rider” engine may be mentioned as another small hot-air motor which follows nearly the Stirling cycle of operations.

Fig. 2—Robinson’s form of Stirling’s Engine.

An attempt to develop a powerful air-engine was made in America about 1833 by John Ericsson, who applied it to marine propulsion in the ship “Caloric,” but without permanent success. Like Stirling, Ericsson used a regenerator, but with this difference that the pressure instead of the volume of the air remained constant while it passed in each direction through the regenerator. Cold air was compressed by a pump into a receiver, where it was kept cool during compression and from which it passed through a regenerator into the working cylinder. In so passing it took up heat and expanded. It was then allowed to expand further, taking in heat from a furnace under the cylinder and falling in pressure. This expansion was continued till the pressure of the working air fell nearly to that of the atmosphere. It was then discharged through the regenerator, depositing heat for the next charge of air in turn to take up. The indicator diagram approximated to a form made up of two isothermal lines and two lines of constant pressure.

In the transmission of power by compressed air (see Power Transmission) the air-driven motors are for the most part machines resembling steam-engines in the general features of their pistons, cylinders, valves and so forth. Such machines are not properly described as air-engines since their function is not the conversion of heat into work. Incidentally, however, they do in some cases partially discharge that function, namely, when what is called a “preheater” is used to warm up the compressed air before it enters in the motor cylinder. The object of this device is not, primarily, to produce work from heat, but to escape the inconveniences that would otherwise arise through extreme cooling of the air during its expansion. Without preheating the expanding air becomes so cold as to be liable to deposit snow from the moisture held in suspension, and thereby to clog the valves. With preheating this is avoided, and the amount of work done by a given quantity of air is increased by the conversion into work of a part of the supplementary energy which the preheater supplies in the form of heat. (J. A. E.)

AIREY, RICHARD AIREY, Baron (1803–1881), British general, was the son of Lieutenant-General Sir George Airey (1761–1833) and was born in 1803. He entered the army in 1821, became captain in 1825, and served on the staff of Sir Frederick Adam in the Ionian Islands (1827–1830) and on that of Lord Aylmer in North America (1830–1832). In 1838 Airey, then a lieutenant-colonel, went to the Horse Guards, Where in 1852 he became military secretary to the commander-in-chief, Lord Hardinge. In 1854 he was given a brigade command in the army sent out to the East; from which, however, he was immediately transferred to the onerous and difficult post of quartermaster-general to Lord Raglan, in which capacity he served through the campaign in the Crimea. He was made a major-general in December 1854, and it was universally recognized in the army that he was the best soldier on Lord Raglan’s staff. He was made a K.C.B., and was reported upon most favourably by his superiors, Lord Raglan and Sir J. Simpson. Airey was a quartermaster-general in the older sense of the word, i.e. a chief of the general staff, but a different view of the duties of the office was then becoming recognized. Public opinion held him and his department responsible for the failures and mismanagement of the commissariat. Airey demanded an inquiry on his return to England and cleared himself completely, but he never recovered from the effects of the unjust persecution of which he had been made the victim, though the popular view was not shared by his military superiors. He gave up his post at the front to become quartermaster-general to the forces at home. In 1862 he was promoted lieutenant-general, and from 1865 to 1870 he was governor of Gibraltar, receiving the G.C.B. in 1867. In 1870 he became adjutant-general at headquarters, and in 1871 attained the full rank of general. In 1876, on his retirement, he was created a peer, and in 1879–1880 he presided over the celebrated Airey commission on army reform. He died at the house of Lord Wolseley, at Leatherhead, on the 14th of September 1881.

AIR-GUN, a gun in which the force employed to propel the bullet is the elasticity of compressed atmospheric air. It has attached to it, or constructed in it, a reservoir of compressed air, a portion of which, liberated into the space behind the bullet when the trigger is pulled, propels the bullet from the barrel by its expansion. The common forms of air-gun, which are merely toys, are charged by compressing a spiral spring, one end of which forms a piston working in a cylinder; when released by a pull on the trigger, this spring expands, and the air forced out in front of it propels the bullet. Air-guns of this kind are sometimes made to resemble walking-sticks and are then known as air-canes.

AIRY, SIR GEORGE BIDDELL (1801–1892), British Astronomer Royal, was born at Alnwick on the 27th of July 1801. He came of a long line of Airys who traced their descent back to a family of the same name residing at Kentmere, in Westmorland, in the 14th century; but the branch to which he belonged, having suffered in the civil wars, removed to Lincolnshire, where for several generations they lived as farmers. George Airy was educated first at elementary schools in Hereford, and afterwards at Colchester Grammar School. In 1819 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, as a sizar. Here he had a brilliant career, and seems to have been almost immediately recognized as the leading man of his year. In 1822 he was elected scholar of Trinity, and in the following year he graduated as senior Wrangler and obtained first Smith’s prize. On the 1st of October 1824 he was elected fellow of Trinity, and in December 1826 was appointed Lucasian professor of mathematics in succession to Thomas Turton. This chair he held for little more than a year, being elected in February 1828 Plumian professor of astronomy and director of the new Cambridge observatory. Some idea of his activity as a writer on mathematical and physical subjects during these early years may be gathered from the fact that previous to this appointment he had contributed no less than three important memoirs to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, and eight to the Cambridge Philosophical Society. At the Cambridge observatory Airy soon gave evidence of his remarkable power of organization. The only telescope erected in the establishment when he took it in charge was the transit instrument, and to this he vigorously devoted himself. By the adoption of a regular system of work, and a careful plan of reduction, he was able to keep his observations reduced practically up to date, and published them annually with a degree of punctuality which astonished his contemporaries. Before long a mural circle was installed, and regular observations were instituted with it in 1833. In the same year the duke of Northumberland presented the Cambridge observatory with a fine object-glass of 12 in. aperture, which was mounted according to Airy’s designs and under his superintendence, although the erection was not completed until after his removal to Greenwich in 1835. Airy’s writings during this time are divided between mathematical