filled with lyddite, melinite, &c., they are called high-explosive (H.E.) shell (see below). Common shell for modern high-velocity guns may be made of cast steel or forged steel; those made of cast iron are now generally made for practice, as they are found to break up on impact, even against earthworks, before the fuze has time to act; the bursting charge is, therefore, not ignited or only ignited after the shell has broken up, the effect of the bursting charge being lost in either case. So long as the shell is strong enough to resist the shocks of discharge and impact against earth or thin steel plates, it should be designed to contain as large a bursting charge as possible and to break up into a large number of medium-sized pieces. Their effect between decks is generally more far-reaching than lyddite shell, but the purely local effect is less. Light structures, which, at a short distance from the point of burst, successfully resist lyddite shell and confine the effect of the explosion, may be destroyed by the shower of heavy pieces produced by the burst of a large common shell.

|

| Fig. 6.—Pointed Common Shell (cast steel). |

To prevent the premature explosion of the shell, by the friction of the grains of powder on discharge, it is heated and coated internally with a thick lacquer, which on cooling presents a smooth surface. Besides this the bursting charge of all shell of 4-in. calibre and upwards (also with all other natures except shrapnel) is contained in a flannel or canvas bag. The bag is inserted through the fuze hole and the bursting charge of pebble and fine grain powder gradually poured in. The shell is tapped on the outside by a wood mallet to settle the powder down. When all the powder has been got in, the neck of the bag is tied and pushed through the fuze hole. A few small shalloon primer bags, filled with seven drams of fine grain powder, are then inserted to fill up the shell and carry the flash from the fuze through the burster bag.

In the United States specially long common shell called torpedo shell, about 4·7 calibres in length, are employed with the coast artillery 12-in. mortars. They were made of cast steel, but owing to a premature explosion in a mortar, supposed to be due to weakness of the shell, they are now made of forged steel. The weight of the usual projectile for this mortar is 850 ℔. The torpedo shell, however, weighs 1000 ℔ and contains 137 ℔ of high explosive; it is not intended for piercing armour but for producing a powerful explosion on the armoured deck of a warship. The compression, and consequent generation of heat on discharge of the charge in these long shell, render them liable to premature explosion if fired with high velocities. Some inventors have, therefore, sought to overcome this by dividing the shell transversely into compartments and so making each portion of the charge comparatively short.

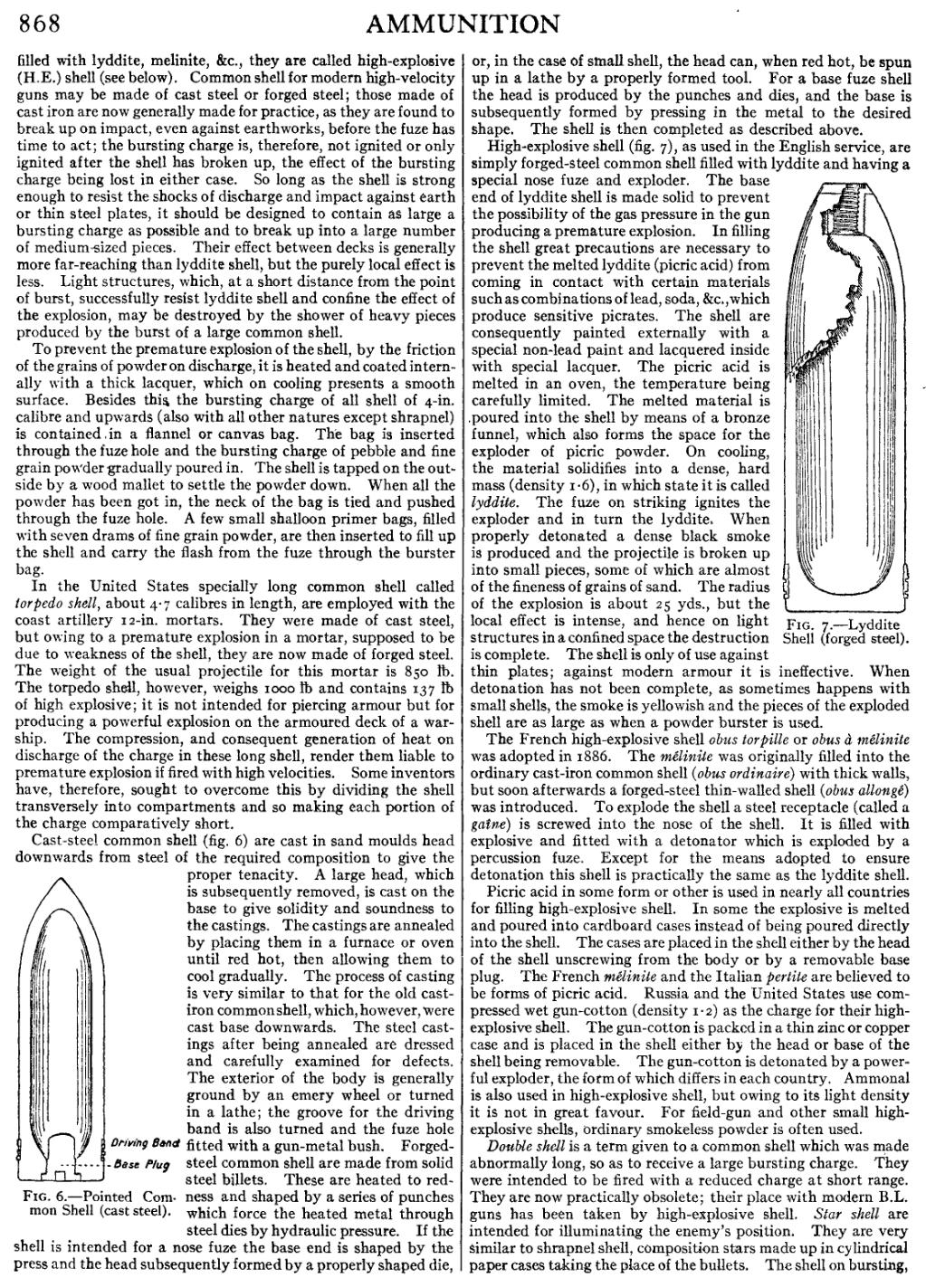

Cast-steel common shell (fig. 6) are cast in sand moulds head downwards from steel of the required composition to give the proper tenacity. A large head, which is subsequently removed, is cast on the base to give solidity and soundness to the castings. The castings are annealed by placing them in a furnace or oven until red hot, then allowing them to cool gradually. The process of casting is very similar to that for the old cast-iron common shell, which, however, were cast base downwards. The steel castings after being annealed are dressed and carefully examined for defects. The exterior of the body is generally ground by an emery wheel or turned in a lathe; the groove for the driving band is also turned and the fuze hole fitted with a gun-metal bush. Forged-steel common shell are made from solid steel billets. These are heated to redness and shaped by a series of punches which force the heated metal through steel dies by hydraulic pressure. If the shell is intended for a nose fuze the base end is shaped by the press and the head subsequently formed by a properly shaped die, or, in the case of small shell, the head can, when red hot, be spun up in a lathe by a properly formed tool. For a base fuze shell the head is produced by the punches and dies, and the base is subsequently formed by pressing in the metal to the desired shape. The shell is then completed as described above.

|

| Fig. 7.—Lyddite Shell (forged steel). |

High-explosive shell (fig. 7), as used in the English service, are simply forged-steel common shell filled with lyddite and having a special nose fuze and exploder. The base end of lyddite shell is made solid to prevent, the possibility of the gas pressure in the gun producing a premature explosion. In filling, the shell great precautions are necessary to prevent the melted lyddite (picric acid) from coming in contact with certain materials such as combinations of lead, soda, &c., which produce sensitive picrates. The shell are consequently painted externally with a special non-lead paint and lacquered inside with special lacquer. The picric acid is melted in an oven, the temperature being carefully limited. The melted material is poured into the shell by means of a bronze funnel, which also forms the space for the exploder of picric powder. On cooling, the material solidifies into a dense, hard mass (density 1·6), in which state it is called lyddite. The fuze on striking ignites the exploder and in turn the lyddite. When properly detonated a dense black smoke is produced and the projectile is broken up into small pieces, some of which are almost of the fineness of grains of sand. The radius of the explosion is about 25 yds., but the local effect is intense, and hence on light structures in a confined space the destruction is complete. The shell is only of use against thin plates; against modern armour it is ineffective. When detonation has not been complete, as sometimes happens with small shells, the smoke is yellowish and the pieces of the exploded shell are as large as when a powder burster is used.

The French high-explosive shell obus torpille or obus à mélinite was adopted in 1886. The mélinite was originally filled into the ordinary cast-iron common shell (obus ordinaire) with thick walls, but soon afterwards a forged-steel thin-walled shell (obus allongé) was introduced. To explode the shell a steel receptacle (called a gaîne) is screwed into the nose of the shell. It is filled with explosive and fitted with a detonator which is exploded by a percussion fuze. Except for the means adopted to ensure detonation this shell is practically the same as the lyddite shell.

Picric acid in some form or other is used in nearly all countries for filling high-explosive shell. In some the explosive is melted and poured into cardboard cases instead of being poured directly into the shell. The cases are placed in the shell either by the head of the shell unscrewing from the body or by a removable base plug. The French mélinite and the Italian pertite are believed to be forms of picric acid. Russia and the United States use compressed wet gun-cotton (density 1·2) as the charge for their high-explosive shell. The gun-cotton is packed in a thin zinc or copper case and is placed in the shell either by the head or base of the shell being removable. The gun-cotton is detonated by a powerful exploder, the form of which differs in each country. Ammonal is also used in high-explosive shell, but owing to its light density it is not in great favour. For field-gun and other small high-explosive shells, ordinary smokeless powder is often used.

Double shell is a term given to a common shell which was made abnormally long, so as to receive a large bursting charge. They were intended to be fired with a reduced charge at short range. They are now practically obsolete; their place with modern B.L. guns has been taken by high-explosive shell. Star shell are intended for illuminating the enemy’s position. They are very similar to shrapnel shell, composition stars made up in cylindrical paper cases taking the place of the bullets. The shell on bursting,