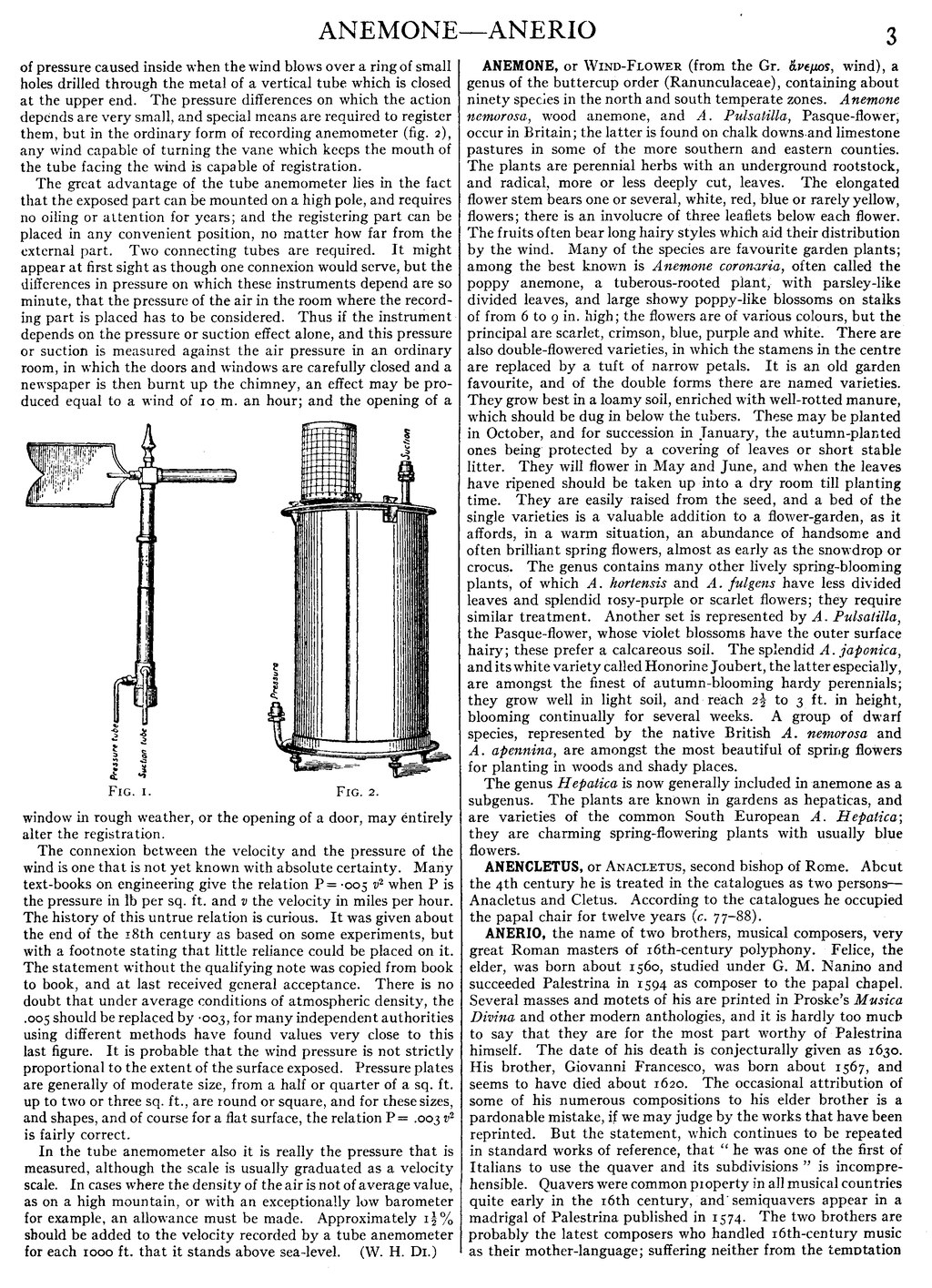

of pressure caused inside when the wind blows over a ring of small holes drilled through the metal of a vertical tube which is closed at the upper end. The pressure differences on which the action depends are very small, and special means are required to register them, but in the ordinary form of recording anemometer (fig. 2), any wind capable of turning the vane which keeps the mouth of the tube facing the wind is capable of registration.

| |

| Fig. 1. | Fig. 2. |

The great advantage of the tube anemometer lies in the fact that the exposed part can be mounted on a high pole, and requires no oiling or attention for years; and the registering part can be placed in any convenient position, no matter how far from the external part. Two connecting tubes are required. It might appear at first sight as though one connexion would serve, but the differences in pressure on which these instruments depend are so minute, that the pressure of the air in the room where the recording part is placed has to be considered. Thus if the instrument depends on the pressure or suction effect alone, and this pressure or suction is measured against the air pressure in an ordinary room, in which the doors and windows are carefully closed and a newspaper is then burnt up the chimney, an effect may be produced equal to a wind of 10 m. an hour; and the opening of a window in rough weather, or the opening of a door, may entirely alter the registration.

The connexion between the velocity and the pressure of the wind is one that is not yet known with absolute certainty. Many text-books on engineering give the relation P = ⋅005 v 2 when P is the pressure in ℔ per sq. ft. and v the velocity in miles per hour. The history of this untrue relation is curious. It was given about the end of the 18th century as based on some experiments, but with a footnote stating that little reliance could be placed on it. The statement without the qualifying note was copied from book to book, and at last received general acceptance. There is no doubt that under average conditions of atmospheric density, the .005 should be replaced by ⋅003, for many independent authorities using different methods have found values very close to this last figure. It is probable that the wind pressure is not strictly proportional to the extent of the surface exposed. Pressure plates are generally of moderate size, from a half or quarter of a sq. ft. up to two or three sq. ft., are round or square, and for these sizes, and shapes, and of course for a flat surface, the relation P = .003 v 2 is fairly correct.

In the tube anemometer also it is really the pressure that is measured, although the scale is usually graduated as a velocity scale. In cases where the density of the air is not of average value, as on a high mountain, or with an exceptionally low barometer for example, an allowance must be made. Approximately 112% should be added to the velocity recorded by a tube anemometer for each 1000 ft. that it stands above sea-level. (W. H. Di.)

ANEMONE, or Wind-Flower (from the Gr. ἄνεμος, wind), a genus of the buttercup order (Ranunculaceae), containing about ninety species in the north and south temperate zones. Anemone nemorosa, wood anemone, and A. Pulsatilla, Pasque-flower, occur in Britain; the latter is found on chalk downs and limestone pastures in some of the more southern and eastern counties. The plants are perennial herbs with an underground rootstock, and radical, more or less deeply cut, leaves. The elongated flower stem bears one or several, white, red, blue or rarely yellow, flowers; there is an involucre of three leaflets below each flower. The fruits often bear long hairy styles which aid their distribution by the wind. Many of the species are favourite garden plants; among the best known is Anemone coronaria, often called the poppy anemone, a tuberous-rooted plant, with parsley-like divided leaves, and large showy poppy-like blossoms on stalks of from 6 to 9 in. high; the flowers are of various colours, but the principal are scarlet, crimson, blue, purple and white. There are also double-flowered varieties, in which the stamens in the centre are replaced by a tuft of narrow petals. It is an old garden favourite, and of the double forms there are named varieties. They grow best in a loamy soil, enriched with well-rotted manure, which should be dug in below the tubers. These may be planted in October, and for succession in January, the autumn-planted ones being protected by a covering of leaves or short stable litter. They will flower in May and June, and when the leaves have ripened should be taken up into a dry room till planting time. They are easily raised from the seed, and a bed of the single varieties is a valuable addition to a flower-garden, as it affords, in a warm situation, an abundance of handsome and often brilliant spring flowers, almost as early as the snowdrop or crocus. The genus contains many other lively spring-blooming plants, of which A. hortensis and A. fulgens have less divided leaves and splendid rosy-purple or scarlet flowers; they require similar treatment. Another set is represented by A. Pulsatilla, the Pasque-flower, whose violet blossoms have the outer surface hairy; these prefer a calcareous soil. The splendid A. japonica, and its white variety called Honorine Joubert, the latter especially, are amongst the finest of autumn-blooming hardy perennials; they grow well in light soil, and reach 212 to 3 ft. in height, blooming continually for several weeks. A group of dwarf species, represented by the native British A. nemorosa and A. apennina, are amongst the most beautiful of spring flowers for planting in woods and shady places.

The genus Hepatica is now generally included in anemone as a subgenus. The plants are known in gardens as hepaticas, and are varieties of the common South European A. Hepatica; they are charming spring-flowering plants with usually blue flowers.

ANENCLETUS, or Anacletus, second bishop of Rome. About the 4th century he is treated in the catalogues as two persons—Anacletus and Cletus. According to the catalogues he occupied the papal chair for twelve years (c. 77–88).

ANERIO, the name of two brothers, musical composers, very great Roman masters of 16th-century polyphony. Felice, the elder, was born about 1560, studied under G. M. Nanino and succeeded Palestrina in 1594 as composer to the papal chapel. Several masses and motets of his are printed in Proske’s Musica Divina and other modern anthologies, and it is hardly too much to say that they are for the most part worthy of Palestrina himself. The date of his death is conjecturally given as 1630. His brother, Giovanni Francesco, was born about 1567, and seems to have died about 1620. The occasional attribution of some of his numerous compositions to his elder brother is a pardonable mistake, if we may judge by the works that have been reprinted. But the statement, which continues to be repeated in standard works of reference, that “he was one of the first of Italians to use the quaver and its subdivisions” is incomprehensible. Quavers were common property in all musical countries quite early in the 16th century, and semiquavers appear in a madrigal of Palestrina published in 1574. The two brothers are probably the latest composers who handled 16th-century music as their mother-language; suffering neither from the temptation