and C. Colombo, Geografia Argentina (Buenos Aires, 1905); E. von Rosen, Archaeological Researches on the Frontier of Argentina and Bolivia 1901–1902 (Stockholm, 1904); Arturo B. Carranza, Constitución Nacional y Constituciones Provinciales Vigentes (Buenos Aires, 1898); Angelo de Gubernatis, L’Argentina (Firenze, 1898); Meliton Gonzales, El Gran Chaco Argentino (Buenos Aires, 1890); John Grant & Sons, The Argentine Year Book (Buenos Aires, 1902 et seq.); Francis Latzina, Diccionario Geografico Argentino (Buenos Aires, 1891); Géographie de la République Argentine (Buenos Aires, 1890); L’Agriculture et l’Elevage dans la République Argentine (Paris, 1889); Bartolomé Mitre, Historia de San Martin y de la Emancipación Sud-Americana, según nuevos documentos (3 vols., Buenos Aires, 1887); Historia de Belgrano y de la Independencia Argentina (3 vols., Buenos Aires, 1883); Felipe Soldan, Diccionario Geografico Estadistico Nacional Argentino (Buenos Aires, 1885); Thomas A. Turner, Argentina and the Argentines (New York and London, 1892); Estanislao S. Zeballos, Descripción Amena de la Republica Argentina (3 vols., Buenos Aires, 1881); Anuario de la Direción General de Estadistica 1898 (Buenos Aires, 1899); Charles Wiener, La République Argentine (Paris, 1899); Segundo Censo República Argentina (3 vols., Buenos Aires, 1898); Handbook of the Argentine Republic (Bureau of the American Republics, Washington, 1892–1903). (A. J. L.)

ARGENTINE, a former city of Wyandotte county, Kansas, U.S.A., since 1910 a part of Kansas City, on the S. bank of the Kansas river, just above its mouth. Pop. (1890) 4732; (1900) 5878, of whom 623 were foreign-born and 603 of negro descent; (1905, state census) 6053. It is served by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fé railway, which maintains here yards and machine shops. The streets of the city run irregularly up the steep face of the river bluffs. Its chief industrial establishment is that of the United Zinc and Chemical Company, which has here one of the largest plants of its kind in the country. There are large grain interests. The site was platted in 1880, and the city was first incorporated in 1882 and again, as a city of the second class, in 1889.

ARGENTITE, a mineral which belongs to the galena group, and is cubic silver sulphide (Ag2S). It is occasionally found as uneven cubes and octahedra, but more often as dendritic or earthy masses, with a blackish lead-grey colour and metallic lustre. The cubic cleavage, which is so prominent a feature in galena, is here present only in traces. The mineral is perfectly sectile and has a shining streak; hardness 2·5, specific gravity 7·3. It occurs in mineral veins, and when found in large masses, as in Mexico and in the Comstock lode in Nevada, it forms an important ore of silver. The mineral was mentioned so long ago as 1529 by G. Agricola, but the name argentite (from the Lat. argentum, “silver”) was not used till 1845 and is due to W. von Haidinger. Old names for the species are Glaserz, silver-glance and vitreous silver. A cupriferous variety, from Jalpa in Tabasco, Mexico, is known as jalpaite. Acanthite is a supposed dimorphous form, crystallizing in the orthorhombic system, but it is probable that the crystals are really distorted crystals of argentite. (L. J. S.)

ARGENTON, a town of western France, in the department of Indre, on the Creuse, 19 m. S.S.W. of Châteauroux on the Orléans railway. Pop. (1906) 5638. The river is crossed by two bridges, and its banks are bordered by picturesque old houses. There are numerous tanneries, and the manufacture of boots and shoes and linen goods is carried on. The site of the ancient Argentomagus lies a little to the north.

ARGHANDAB, a river of Afghanistan, about 250 m. in length. It rises in the Hazara country north-west of Ghazni, and flowing south-west falls into the Helmund 20 m. below Girishk. Very little is known about its upper course. It is said to be shallow, and to run nearly dry in height of summer; but when its depth exceeds 3 ft. its great rapidity makes it a serious obstacle to travellers. In its lower course it is much used for irrigation, and the valley is cultivated and populous; yet the water is said to be somewhat brackish. It is doubtful whether the ancient Arachotus is to be identified with the Arghandab or with its chief confluent the Tarnak, which joins it on the left about 30 m. S.W. of Kandahar. The two rivers run nearly parallel, inclosing the backbone of the Ghilzai plateau. The Tarnak is much the shorter (length about 200 m.) and less copious. The ruins at Ulân Robât, supposed to represent the city Arachosia, are in its basin; and the lake known as Ab-i-Istâda, the most probable representative of Lake Arachotus, is near the head of the Tarnak, though not communicating with it. The Tarnak is dammed for irrigation at intervals, and in the hot season almost exhausted. There is a good deal of cultivation along the river, but few villages. The high road from Kabul to Kandahar passes this way (another reason for supposing the Tarnak to be Arachotus), and the people live off the road to avoid the onerous duties of hospitality.

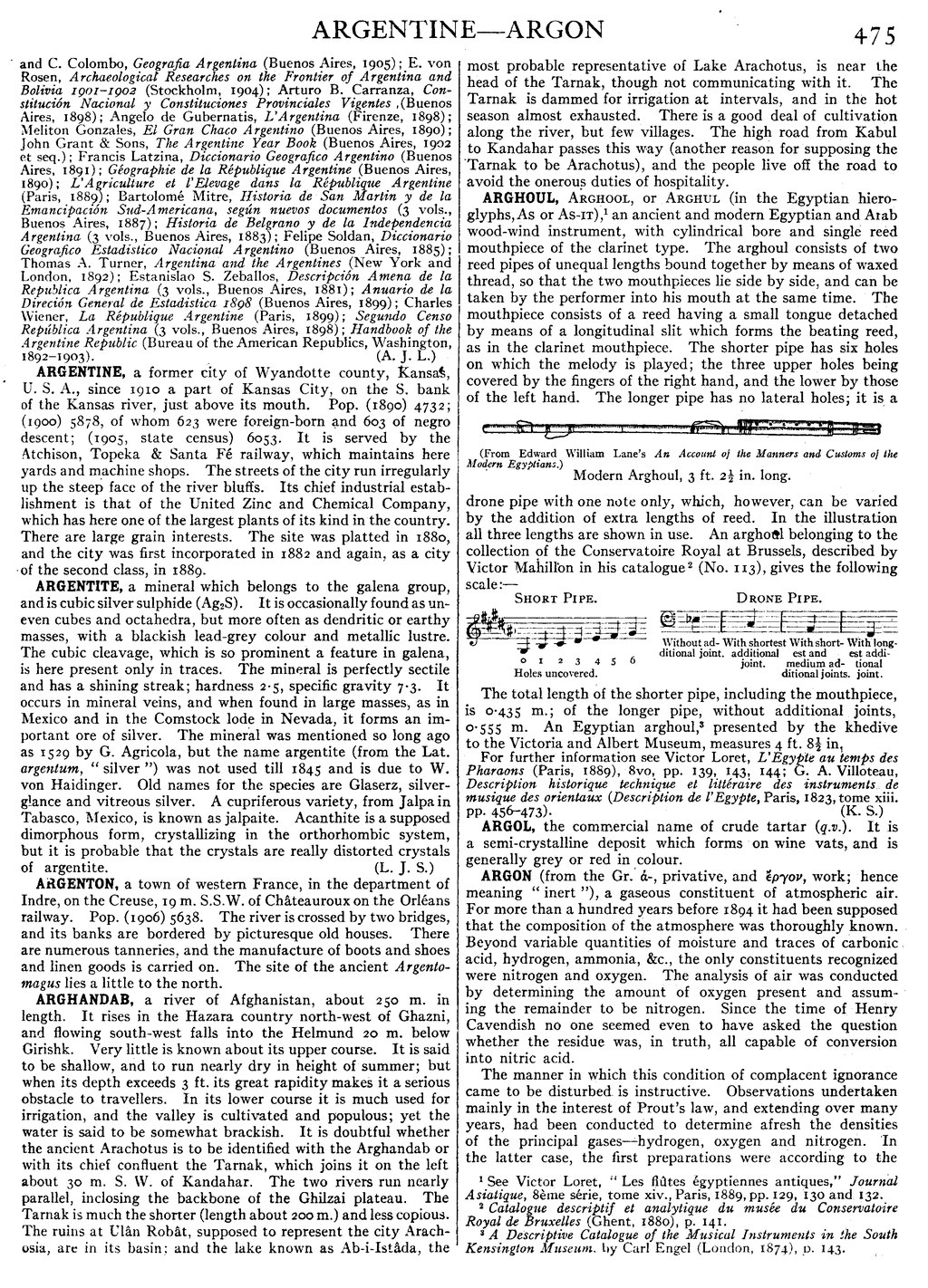

ARGHOUL, Arghool, or Arghul (in the Egyptian hieroglyphs, As or As-it),[1] an ancient and modern Egyptian and Arab wood-wind instrument, with cylindrical bore and single reed mouthpiece of the clarinet type. The arghoul consists of two reed pipes of unequal lengths bound together by means of waxed thread, so that the two mouthpieces lie side by side, and can be taken by the performer into his mouth at the same time. The mouthpiece consists of a reed having a small tongue detached by means of a longitudinal slit which forms the beating reed, as in the clarinet mouthpiece. The shorter pipe has six holes on which the melody is played; the three upper holes being covered by the fingers of the right hand, and the lower by those of the left hand. The longer pipe has no lateral holes; it is a drone pipe with one note only, which, however, can be varied by the addition of extra lengths of reed. In the illustration all three lengths are shown in use. An arghoul belonging to the collection of the Conservatoire Royal at Brussels, described by Victor Mahillon in his catalogue[2] (No. 113), gives the following scale:—

| Short Pipe. | Drone Pipe. | |||

Holes uncovered. |

||||

| Without additional joint. |

With shortest additional joint. |

With shortest and medium additional joints. |

With longest additional joint. | |

| (From Edward William Lane’s An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians.) |

| Modern Arghoul, 3 ft. 212 in. long. |

The total length of the shorter pipe, including the mouthpiece, is 0·435 m.; of the longer pipe, without additional joints, 0·555 m. An Egyptian arghoul,[3] presented by the khedive to the Victoria and Albert Museum, measures 4 ft. 812 in.

For further information see Victor Loret, L’Egypte au temps des Pharaons (Paris, 1889), 8vo, pp. 139, 143, 144; G. A. Villoteau, Description historique technique et littéraire des instruments de musique des orientaux (Description de l’Egypte, Paris, 1823, tome xiii, pp. 456–473). (K. S.)

ARGOL, the commercial name of crude tartar (q.v.). It is a semi-crystalline deposit which forms on wine vats, and is generally grey or red in colour.

ARGON (from the Gr. ἀ–, privative, and ἒργον, work; hence meaning “inert”), a gaseous constituent of atmospheric air. For more than a hundred years before 1894 it had been supposed that the composition of the atmosphere was thoroughly known. Beyond variable quantities of moisture and traces of carbonic acid, hydrogen, ammonia, &c., the only constituents recognized were nitrogen and oxygen. The analysis of air was conducted by determining the amount of oxygen present and assuming the remainder to be nitrogen. Since the time of Henry Cavendish no one seemed even to have asked the question whether the residue was, in truth, all capable of conversion into nitric acid.

The manner in which this condition of complacent ignorance came to be disturbed is instructive. Observations undertaken mainly in the interest of Prout’s law, and extending over many years, had been conducted to determine afresh the densities of the principal gases—hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen. In the latter case, the first preparations were according to the

- ↑ See Victor Loret. “Les flûtes égyptiennes antiques,” Journal Asiatique, 8ème série, tome xiv., Paris, 1889, pp. 129, 130 and 132.

- ↑ Catalogue descriptif et analytique du musée du Conservatoire Royal de Bruxelles (Ghent, 1880), p. 141.

- ↑ A Descriptive Catalogue of the Musical Instruments in the South Kensington Museum, by Carl Engel (London, 1874), p. 143.