crystal such as represented in fig. 3, the smaller and dull tetrahedral faces s are situated at the analogous poles (which become positively electrified when the crystal is heated), and the larger and bright tetrahedral faces s′ at the antilogous poles.

The characters so far enumerated are strictly in accordance with cubic symmetry, but when a crystal is examined in polarized light, it will be seen to be doubly refracting, as was first observed by Sir David Brewster in 1821. Thin sections show twin-lamellae, and a division into definite areas which are optically biaxial. By cutting sections in suitable directions, it may be proved that a rhombic dodecahedral crystal is really built up of twelve orthorhombic pyramids, the apices of which meet in the centre and the bases coincide with the dodecahedral faces of the compound (pseudo-cubic) crystal. Crystals of other forms show other types of internal structure. When the crystals are heated these optical characters change, and at a temperature of 265° the crystals suddenly become optically isotropic; on cooling, however, the complexity of internal structure reappears. Various explanations have been offered to account for these “optical anomalies” of boracite. Some observers have attributed them to alteration, others to internal strains in the crystals, which originally grew as truly cubic at a temperature above 265°. It would, however, appear that there are really two crystalline modifications of the boracite substance, a cubic modification stable above 265° and an orthorhombic (or monoclinic) one stable at a lower temperature. This is strictly analogous to the case of silver iodide, of which cubic and rhombohedral modifications exist at different temperatures; but whereas rhombohedral as well as pseudo-cubic crystals of silver iodide (iodyrite) are known in nature, only pseudo-cubic crystals of boracite have as yet been met with.

Chemically, boracite is a magnesium borate and chloride with the formula Mg7Cl2B16O30—A small amount of iron is sometimes present, and an iron-boracite with half the magnesium replaced by ferrous iron has been called huyssenite. The mineral is insoluble in water, but soluble in hydrochloric acid. On exposure it is liable to slow alteration, owing to the absorption of water by the magnesium chloride: an altered form is known as parasite.

In addition to embedded crystals, a massive variety, known as stassfurtite, occurs as nodules in the salt deposits at Stassfurt in Prussia: that from the carnallite layer is compact, resembling fine-grained marble, and white or greenish in colour, whilst that from the kainite layer is soft and earthy, and yellowish or reddish in colour. (L. J. S.)

BORAGE (pronounced like “courage”; possibly from Lat.

borra, rough hair), a herb (Borago officinalis) with bright blue

flowers and hairy leaves and stem, considered to have some

virtue as a cordial and a febrifuge; used as an ingredient in

salads or in making claret-cup, &c.

BORAGINACEAE, an order of plants belonging to the sympetalous

section of dicotyledons, and a member of the series

Tubiflorae. It is represented in Britain by bugloss (Echium)

(fig. 1), comfrey (Symphytum), Myosotis, hounds-tongue (Cynoglossum)

(fig. 2), and other genera, while borage (Borago officinalis)

(fig. 3) occurs as a garden escape in waste ground.

The plants are rough-haired annual or perennial herbs, more rarely

shrubby or arborescent, as in Cordia and Ehretia, which are

tropical or sub-tropical. The leaves, which are generally

alternate, are usually entire and narrow: the radical leaves in

some genera, as Pulmonaria (lungwort) and Cynoglossum, differ

in form from the stem-leaves, being generally broader and sometimes

heart-shaped. A characteristic feature is the one-sided

(dorsiventral) inflorescence, well illustrated in forget-me-not and

other species of Myosotis; the cyme is at first closely coiled,

becoming uncoiled as the flowers open. At the same time there

is often a change in colour in the flowers, which are red in bud,

becoming blue as they expand, as in Myosotis, Echium, Symphytum

and others. The flowers are generally regular; the

form of the corolla varies widely. Thus in borage it is rotate,

tubular in comfrey, funnel-shaped in hounds-tongue, and salver-shaped

in alkanet (Anchusa); the throat is often closed by

scale-like outgrowths from the corolla, forming the so-called

corona. A departure from the usual regular corolla occurs in

Echium and a few allied genera, where it is oblique; in Lycopsis

it is also bent.

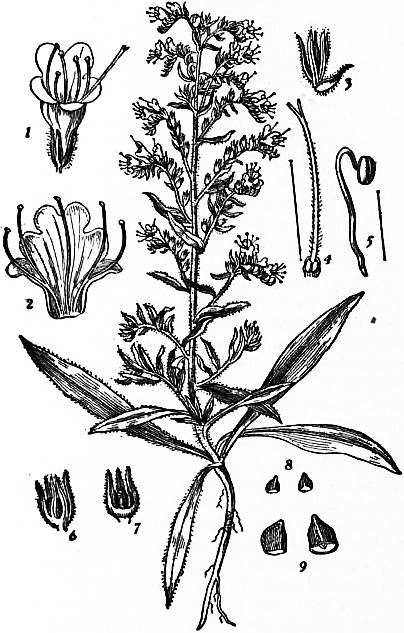

| Fig. 1.—Viper’s Bugloss (Echium vulgare), about 14 nat. size. | |

1. Single flower, about nat. size. |

6. Calyx surrounding nutlets. |

The five stamens alternate in position with the lobes of the

corolla. The ovary, of two carpels, is seated on a ring-like disk

which secretes honey.

Fig.2.—(1) Inflorescence of

Forget-me-not; (2) ripe fruits.

Each carpel becomes divided by a

median constriction in four portions, each containing one

ovule; the style springs from the centre of the group of four

divisions.

The flowers show well-marked adaptation to insect-visits.

Their colour and tendency to arrangement on one surface, with

the presence of honey, serve to

attract insects. The scales around

the throat of the corolla protect

the pollen and honey from wet or

undesirable visitors, and by their

difference in colour from the corolla-lobes,

as in the yellow eye of

forget-me-not, may serve to indicate

the position of the honey. In most

genera the fruit consists of one-seeded

nutlets, generally four, but

one or more may be undeveloped.

The shape of the nutlet and the

character of its coat are very varied.

Thus in Lithospermum the nutlets

are hard like a stone, in Myosotis

usually polished, in Cynoglossum

covered with bristles, &c.

The order is widely spread in temperate and tropical regions, and contains 85 genera with about 1200 species. Its chief centre is the Mediterranean region, whence it extends over central