the space in the body cavity. The food passes into these lobes, which may be found crowded with diatoms, and without doubt a large part of the digestion is carried on inside the liver. The stomach, oesophagus and intestine are ciliated on their inner surface. The intestine is slung by a median dorsal and ventral mesentery which divides the body cavity into two symmetrically shaped halves; it is “stayed” by two transverse septa, the anterior or gastroparietal band running from the stomach to the body wall and the posterior or ileoparietal band running from the intestine to the body wall. None of these septa is complete, and the various parts of the central body cavity freely communicate with one another. In Rhynchonella, where there are two pairs of kidneys, the internal opening of the anterior pair is supported by the gastroparietal band and that of the posterior pair by the ileoparietal band. The latter pair alone persists in all other genera.

The kidneys or nephridia open internally by wide funnel-shaped nephridiostomes and externally by small pores on each side of the mouth near the base of the arms. Each is short, gently curved and devoid of convolutions. They are lined by cells charged with a yellow or brown pigment, and besides their excretory functions they act as ducts through which the reproductive cells leave the body.

Circulatory System.—The structures formerly regarded as pseudohearts have been shown by Huxley to be nephridia; the true heart was described and figured by A. Hancock, but has in many cases escaped the observation of later zoologists. F. Blochmann in 1884, however, observed this organ in the living animal in species of the following genera:—Terebratulina, Magellania [Waldheimia], Rhynchonella, Megathyris (Argiope), Lingula, and Crania (fig. 21). It consists of a definite contractile sac or sacs lying on the dorsal side of the alimentary canal near the oesophagus, and in preparations of Terebratulina made by quickly removing the viscera and examining them in sea-water under a microscope, he was able to count the pulsations, which followed one another at intervals of 30–40 seconds.

|

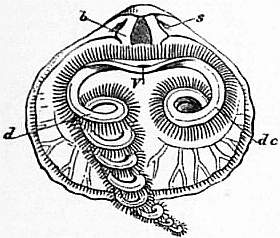

| Fig. 23.—Rhynchonella (Hemithyris) psittacea. Interior of dorsal valve, s, Sockets; b, dental plates; V, mouth; de, labial appendage in its natural position; d, appendage extended or unrolled. |

A vessel—the dorsal vessel—runs forward from the heart along the dorsal surface of the oesophagus. This vessel is nothing but a split between the right and left folds of the mesentery, and its cavity is thus a remnant of the blastocoel. A similar primitive arrangement is thought by F. Blochmann to obtain in the genital arteries. Anteriorly the dorsal vessel splits into a right and a left half, which enter the small arm-sinus and, running along it, give off a blind branch to each tentacle (fig. 21). The right and left halves are connected ventrally to the oesophagus by a short vessel which supplies these tentacles in the immediate neighbourhood of the mouth. There is thus a vascular ring around the oesophagus. The heart gives off posteriorly a second median vessel which divides almost at once into a right and a left half, each of which again divides into two vessels which run to the dorsal and ventral mantles respectively. The dorsal branch sends a blind twig into each of the diverticula of the dorsal mantle-sinus, the ventral branch supplies the nephridia and neighbouring parts before reaching the ventral lobe of the mantle. Both dorsal and ventral branches supply the generative organs.

The blood is a coagulable fluid. Whether it contains corpuscles is not yet determined, but if so they must be few in number. It is a remarkable fact that in Discinisca, although the vessels to the lophophore are arranged as in other Brachiopods, no trace of a heart or of the posterior vessels has as yet been discovered.

Muscles.—The number and position of the muscles differ materially in the two great divisions into which the Brachiopoda have been grouped, and to some extent also in the different genera of which each division is composed. Unfortunately almost every anatomist who has written on the muscles of the Brachiopoda has proposed different names for each muscle, and the confusion thence arising is much to be regretted. In the Testicardines, of which the genus Terebratula may be taken as an example, five or six pairs of muscles are stated by A. Hancock, Gratiolet and others to be connected with the opening and closing of the valves, or with their attachment to or movements upon the peduncle. First of all, the adductors or occlusors consist of two muscles, which, bifurcating near the centre of the shell cavity, produce a large quadruple impression on the internal surface of the small valve (fig. 13, a, a'), and a single divided one towards the centre of the large or ventral valve (fig. 12, a). The function of this pair of muscles is the closing of the valves. Two other pairs have been termed divaricators by Hancock, or cardinal muscles (“muscles diducteurs” of Gratiolet), and have for function the opening of the valves. The divaricators proper are stated by Hancock to arise from the ventral valve, one on each side, a little in advance of and close to the adductors, and after rapidly diminishing in size become attached to the cardinal process, a space or prominence between the sockets in the dorsal valve. The accessory divaricators are, according to the same authority, a pair of small muscles which have their ends attached to the ventral valve, one on each side of the median line, a little behind the united basis of the adductors, and again to the extreme point of the cardinal process. Two pairs of muscles, apparently connected with the peduncle and its limited movements, have been minutely described by Hancock as having one of their extremities attached to this organ. The dorsal adjusters are fixed to the ventral surface of the peduncle, and are again inserted into the hinge-plate in the smaller valve. The ventral adjusters are considered to pass from the inner extremity of the peduncle, and to become attached by one pair of their extremities to the ventral valve, one on each side and a little behind the expanded base of the divaricators. The function of these muscles, according to the same authority, is not only that of erecting the shell; they serve also to attach the peduncle to the shell, and thus effect the steadying of it upon the peduncle. By alternate contracting they can cause a slight rotation of the animal in its stalk.

Such is the general arrangement of the shell muscles in the division composing the articulated Brachiopoda, making allowance for certain unimportant modifications observable in the animals composing the different families and genera thereof. Owing to the strong and tight interlocking of the valves by the means of curved teeth and sockets, many species of Brachiopoda could open their valves but slightly. In some species, such as Thecidea, the animal could raise its dorsal valve at right angles to the plane of the ventral one (fig. 4).

In the Ecardines, of which Lingula and Discina may be quoted as examples, the myology is much more complicated. Of the shell