two parts already named. Except where stated, we deal here primarily with the brain in man.

1. Anatomy

Membranes of the Human Brain.

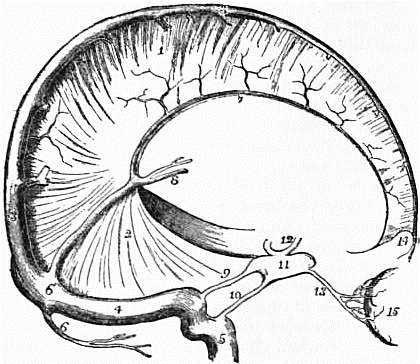

Three membranes named the dura mater, arachnoid and pia mater cover the brain and lie between it and the cranial cavity. The most external of the three is the dura mater, which consists of a cranial and a spinal portion. The cranial part is in contact with the inner table

| Fig. 1.—Dura Mater and Cranial Sinuses. | |

1. Falx cerebri. |

8. Veins of Galen. |

of the skull, and is adherent along the lines of the sutures and to the margins of the foramina, which transmit the nerves, more especially to the foramen magnum. It forms, therefore, for these bones an internal periosteum, and the meningeal arteries which ramify in it are the nutrient arteries of the inner table. As the growth of bone is more active in infancy and youth than in the adult, the adhesion between the dura mater and the cranial bones is greater in early life than at maturity. From the inner surface of the dura mater strong bands pass into the cranial cavity, and form partitions between certain of the subdivisions of the brain. A vertical longitudinal mesial band, named, from its sickle shape, falx cerebri, dips between the two hemispheres of the cerebrum. A smaller sickle-shaped vertical mesial band, the falx cerebelli, attached to the internal occipital crest, passes between the two hemispheres of the cerebellum. A large band arches forward in the horizontal plane of the cavity, from the transverse groove in the occipital bone to the clinoid processes of the sphenoid, and is attached laterally to the upper border of the petrous part of each temporal bone. It separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum, and, as it forms a tent-like covering for the latter, is named tentorium cerebelli. Along certain lines the cranial dura mater splits into two layers to form tubular passages for the transmission of venous blood. These passages are named the venous blood sinuses of the dura mater, and they are lodged in the grooves on the inner surface of the skull referred to in the description of the cranial bones. Opening into these sinuses are numerous veins which convey from the brain the blood that has been circulating through it; and two of these sinuses, called cavernous, which lie at the sides of the body of the sphenoid bone, receive the ophthalmic veins from the eyeballs situated in the orbital cavities. These blood sinuses pass usually from before backwards: a superior longitudinal along the upper border of the falx cerebri as far as the internal occipital protuberance; an inferior longitudinal along its lower border as far as the tentorium, where it joins the straight sinus, which passes back as far as the same protuberance. One or two small occipital sinuses, which lie in the falx cerebelli, also pass to join the straight and longitudinal sinuses opposite this protuberance; several currents of blood meet, therefore, at this spot, and as Herophilus supposed that a sort of whirlpool was formed in the blood, the name torcular Herophili has been used to express the meeting of these sinuses. From the torcular the blood is drained away by two large sinuses, named lateral, which curve forward and downward to the jugular foramina to terminate in the internal jugular veins. In its course each lateral sinus receives two petrosal sinuses, which pass from the cavernous sinus backwards along the upper and lower borders of the petrous part of the temporal bone. The dura mater consists of a tough, fibrous membrane, somewhat flocculent externally, but smooth, glistening, and free on its inner surface. The inner surface has the appearance of a serous membrane, and when examined microscopically is seen to consist of a layer of squamous endothelial cells. Hence the dura mater is sometimes called a fibro-serous membrane. The dura mater is well provided with lymph vessels, which in all probability open by stomata on the free inner surface. Between the dura mater and the subjacent arachnoid membrane is a fine space containing a minute quantity of limpid serum, which moistens the smooth inner surface of the dura and the corresponding smooth outer surface of the arachnoid. It is regarded as equivalent to the cavity of a serous membrane, and is named the sub-dural space.

Arachnoid Mater.—The arachnoid is a membrane of great delicacy and transparency, which loosely envelops both the brain and spinal cord. It is separated from these organs by the pia mater; but between it and the latter membrane is a distinct space, called sub-arachnoid. The sub-arachnoid space is more distinctly marked beneath the spinal than beneath the cerebral parts of the membrane, which forms a looser investment for the cord than for the brain. At the base of the brain, and opposite the fissures between the convolutions of the cerebrum, the interval between the arachnoid and the pia mater can, however, always be seen, for the arachnoid does not, like the pia mater, clothe the sides of the fissures, but passes directly across between the summits of adjacent convolutions. The sub-arachnoid space is subdivided into numerous freely-communicating loculi by bundles of delicate areolar tissue, which bundles are invested, as Key and Retzius have shown, by a layer of squamous endothelium. The space contains a limpid cerebro-spinal fluid, which varies in quantity from 2 drachms to 2 oz., and is most plentiful in the dilatations at the base of the brain known as cisternae. It should be clearly understood that there is no communication between the subdural and sub-arachnoid spaces, but that the latter communicates with the ventricles through openings in the roof of the fourth, and in the descending cornua of the lateral ventricles.

When the skull cap is removed, clusters of granular bodies are usually to be seen imbedded in the dura mater on each side of the superior longitudinal sinus; these are named the Pacchionian bodies. When traced through the dura mater they are found to spring from the arachnoid. The observations of Luschka and Cleland have proved that villous processes invariably grow from the free surface of that membrane, and that when these villi greatly increase in size they form the bodies in question. Sometimes the Pacchionian bodies greatly hypertrophy, occasioning absorption of the bones of the cranial vault and depressions on the upper surface of the brain.

After D. J. Cunningham’s Text-book of Anatomy.

Fig. 2.—Front View of the Medulla, Pons and Mesencephalon of a full-time Human Foetus.

Pia Mater.—This membrane closely invests the whole outer surface of the brain. It dips into the fissures between the convolutions, and a wide prolongation, named velum interpositum, lies in the interior of the cerebrum. With a little care it can be stripped off the brain without causing injury to its substance. At the base of the brain the pia mater is prolonged on to the roots of the cranial nerves. This membrane consists of a delicate connective tissue, in which the arteries of the brain and spinal cord ramify and subdivide into small branches before they penetrate the nervous substance, and in which the veins conveying the blood from the nerve centres lie before they open into the blood sinuses of the cranial dura mater and the extradural venus plexus of the spinal canal.