sewn up to form a bag whilst the barge is being towed to the site. The concrete is thus deposited unset, and readily accommodates itself to the irregularities of the bottom or of the mound of bags; and sufficient liquid grout oozes out of the canvas when the bag is compressed, to unite the bags into a solid mass, so that with the mass concrete on the top, the breakwater forms a monolith. This system has been extended to the portion of the superstructure of the eastern, little-exposed breakwater of Bilbao harbour below low water, where the rubble mound is of moderate height; but this application of the system appears less satisfactory, as settlement of the superstructure on the mound would produce cracks in the set concrete in the bags.

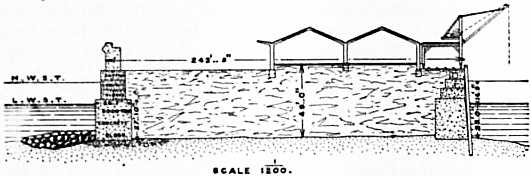

Foundation blocks of 2500 to 3000 tons have been deposited for raising the walls on each side of the wide portion of the Zeebrugge breakwater (fig. 16) from the sea-bottom to above low water, and also 4400-ton blocks along the narrow outer portion (see Harbour), by building iron caissons, Foundations with large blocks. open at the top, in the dry bed of the Bruges ship-canal, lining them with concrete, and after the canal was filled with water, floating them out one by one in calm weather, sinking them in position by admitting water, and then filling them with concrete under water from closed skips which open at the bottom directly they begin to be raised. The firm sea-bed is levelled by small rubble for receiving the large blocks, whose outer toe is protected from undermining by a layer of big blocks of stone extending out for a width of 50 ft.; and then the breakwater walls are raised above high water by 55-ton concrete blocks, set in cement at low tide; and the upper portions are completed by concrete-in-mass within framing.

Sometimes funds are not available for a large plant; and in such cases small upright-wall breakwaters may be constructed in a moderate depth of water on a hard bottom of rock, chalk or boulders, by erecting timber framing in suitable lengths, lining it inside with jute cloth, and then depositing Concrete monoliths. concrete below low water in closed hopper skips lowered to the bottom before releasing the concrete, which must be effected with great care to avoid allowing the concrete to fall through the water. The portion of the breakwater above low water is then raised by tide-work with mass concrete within frames, in which large blocks of stone may be bedded, provided they do not touch one another and are kept away from the face, which should be formed with concrete containing a larger proportion of cement. As long continuous lengths of concrete crack across under variations in temperature, it is advisable to form fine straight divisions across the upper part of a concrete breakwater in construction, as substitutes for irregular cracks.

Upright-wall breakwaters should not be formed with two narrow walls and intermediate filling, as the safety of such a breakwater depends entirely on the sea-wall being maintained intact. A warning of the danger of this system of construction, combined with a high parapet, was furnished by the south breakwater of Newcastle harbour in Dundrum Bay, Ireland, which was breached by a storm in 1868, and eventually almost wholly destroyed; whilst its ruins for many years filled up the harbour which it had been erected to protect. In designing its reconstruction in 1897, it was found possible to provide a solid upright wall of suitable strength with the materials scattered over the harbour, together with an extension needed for providing proper protection at the entrance. This work was completed in 1906.

Upright-wall breakwaters and superstructures are generally made of the same thickness throughout, irrespective of the differences in depth and exposure which are often met with in different parts of the same breakwater. This may be accounted for by the general custom of regarding the top of an upright wall or superstructure as a quay, which should naturally be given a uniform width; and this view has also led to the very general practice of sheltering the top of these structures with a parapet. Generally the width is proportioned to the most exposed part, so that the only result is an excess of expenditure in the inner portion to secure uniformity. When, however, as at Madras, the width of the structure is reduced to a minimum, the action of the sea demonstrates that the strength of the structure must be proportioned to the depth and exposure. In small fishery piers, where great economy is essential to obtain the maximum shelter at limited expense, it appears expedient to make the width of the breakwater proportionate to the depth. This was done in Babbacombe Bay; and in reconstructing the southern breakwater at Newcastle, Ireland, advantage was taken of a change in direction of the outer half to introduce an addition to the width, so as to make the strength of the breakwater proportionate to the increase in depth and exposure. In large structures, however, uniformity of design may be desirable for each straight length of breakwater; though where two or more breakwaters or outer arms enclose a harbour, the design should obviously be modified to suit the depth and exposure. At Colombo harbour, the superstructure of the less exposed north-west breakwater has been made slightly narrower than that of the south-west breakwater; and a simple rubble mound shelters the harbour from the moderate north-east monsoon. In special cases, where a breakwater has to serve as a quay, like the Admiralty pier at Dover, a high parapet wall is essential; but in most cases, where a parapet merely enables the breakwater to be more readily accessible in moderate weather, it would be advisable to keep it very low, or to dispense with it altogether, as at the southern Dover breakwater, the northern breakwater at Sunderland, and the Colombo western breakwaters. This course is particularly expedient in very exposed sites, as a high parapet intensifies the shock of the waves against a breakwater and their erosive recoil. Moreover, when a light has to be attended to at the end of a breakwater, sheltered access can be provided by a subway, as at Sunderland.

Structures in the sea almost always require works of maintenance; and when a severe storm has caused any injury, it is most important to carry out the repairs at the earliest available moment, as the waves rapidly enlarge any holes that they may have formed in weak places. (L. F. V.-H.)

BRÉAL, MICHEL JULES ALFRED (1832– ), French philologist, was born on the 26th of March 1832, at Landau in Rhenish Bavaria, of French parents. After studying at Weissenburg, Metz and Paris, he entered the École Normale in 1852. In 1857 he went to Berlin, where he studied Sanskrit under Bopp and Weber. On his return to France he obtained an appointment in the department of oriental MSS. at the Bibliothèque Impériale. In 1864 he became professor of comparative grammar at the Collège de France, in 1875 member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, in 1879 inspecteur-général of public instruction for higher schools until the abolition of the office in 1888. In 1890 he was made commander of the Legion of Honour. Among his works, which deal mainly with mythological and philological subjects, may be mentioned: L’Étude des origines de la religion Zoroastrienne (1862), for which a prize was awarded him by the Académie des Inscriptions; Hercule et Cacus (1863), in which he disputes the principles of the symbolic school in the interpretation of myths; Le Mythe d’Oedipe (1864); Les Tables Eugubines (1875); Mélanges de mythologie et de linguistique (2nd. ed., 1882); Leçons de mots (1882,1886), Dictionnaire étymologique latin (1885) and Grammaire latine (1890). His Essai de Sémantique (1897), on the signification of words, has been translated into English by Mrs H. Cust with preface by J. P. Postgate. His translation of Bopp’s Comparative Grammar (1866–1874), with introductions, is highly valued. He has also written pamphlets on education in France, the teaching of ancient languages, and the reform of French orthography. In 1906 he published Pour mieux connaître Homère.

BREAM (Abramis), a fish of the Cyprinid family, characterized by a deep, strongly compressed body, with short dorsal and long anal fins, the latter with more than sixteen branched rays, and the small inferior mouth. There are two species in the British Isles, the common bream, A. brama, reaching a length of 2 ft. and a weight of 12 ℔, and the white bream or bream flat, A. blicca, a smaller and, in most places, rarer species. Both occur in slow-running rivers, canals, ponds and reservoirs. Bream are usually despised for the table in England, but fish from large lakes, if well prepared, are by no means deserving of ostracism. In the days of medieval abbeys, when the provident Cistercian monks attached great importance to pond culture, they gave the first place to the tench and bream, the carp still being unknown in the greater part of Europe. At the present day, the poorer Jews in large English cities make a great consumption