4th century the skilled artisans and builders, and the cloth and corn of Britain were equally famous on the continent. This probably was the age when the prosperity and Romanization of the province reached its height. By this time the town populations and the educated among the country-folk spoke Latin, and Britain regarded itself as a Roman land, inhabited by Romans and distinct from outer barbarians.

The civilization which had thus spread over half the island was genuinely Roman, identical in kind with that of the other western provinces of the empire, and in particular with that of northern Gaul. But it was defective in quantity. The elements which compose it are marked by smaller size, less wealth and less splendour than the same elements elsewhere. It was also uneven in its distribution. Large tracts, in particular Warwickshire and the adjoining midlands, were very thinly inhabited. Even densely peopled areas like north Kent, the Sussex coast, west Gloucestershire and east Somerset, immediately adjoin areas like the Weald of Kent and Sussex where Romano-British remains hardly occur.

The administration of the civilized part of the province, while subject to the governor of all Britain, was practically entrusted to local authorities. Each Roman municipality ruled itself and a territory perhaps as large as a small county which belonged to it. Some districts belonged to the Imperial Domains, and were administered by agents of the emperor. The rest, by far the larger part of the country, was divided up among the old native tribes or cantons, some ten or twelve in number, each grouped round some country town where its council (ordo) met for cantonal business. This cantonal system closely resembles that which we find in Gaul. It is an old native element recast in Roman form, and well illustrates the Roman principle of local government by devolution.

In the general framework of Romano-British life the two chief features were the town, and the villa. The towns of the province, as we have already implied, fall into two classes. Five modern cities, Colchester, Lincoln, York, Gloucester and St Albans, stand on the sites, and in some fragmentary fashion bear the names of five Roman municipalities, founded by the Roman government with special charters and constitutions. All of these reached a considerable measure of prosperity. None of them rivals the greater municipalities of other provinces. Besides them we trace a larger number of country towns, varying much in size, but all possessing in some degree the characteristics of a town. The chief of these seem to be cantonal capitals, probably developed out of the market centres or capitals of the Celtic tribes before the Roman conquest. Such are Isurium Brigantum, capital of the Brigantes, 12 m. north-west of York and the most northerly Romano-British town; Ratae, now Leicester, capital of the Coritani; Viroconium, now Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury, capital of the Cornovii; Venta Silurum, now Caerwent, near Chepstow; Corinium, now Cirencester, capital of the Dobuni; Isca Dumnoniorum, now Exeter, the most westerly of these towns; Durnovaria, now Dorchester, in Dorset, capital of the Durotriges; Venta Belgarum, now Winchester; Calleva Atrebatum, now Silchester, 10 m. south of Reading; Durovernum Cantiacorum, now Canterbury; and Venta Icenorum, now Caistor-by-Norwich. Besides these country towns, Londinium (London) was a rich and important trading town, centre of the road system, and the seat of the finance officials of the province, as the remarkable objects discovered in it abundantly prove, while Aquae Sulis (Bath) was a spa provided with splendid baths, and a richly adorned temple of the native patron deity, Sul or Sulis, whom the Romans called Minerva. Many smaller places, too, for example, Magna or Kenchester near Hereford, Durobrivae or Rochester in Kent, another Durobrivae near Peterborough, a site of uncertain name near Cambridge, another of uncertain name near Chesterford, exhibited some measure of town life.

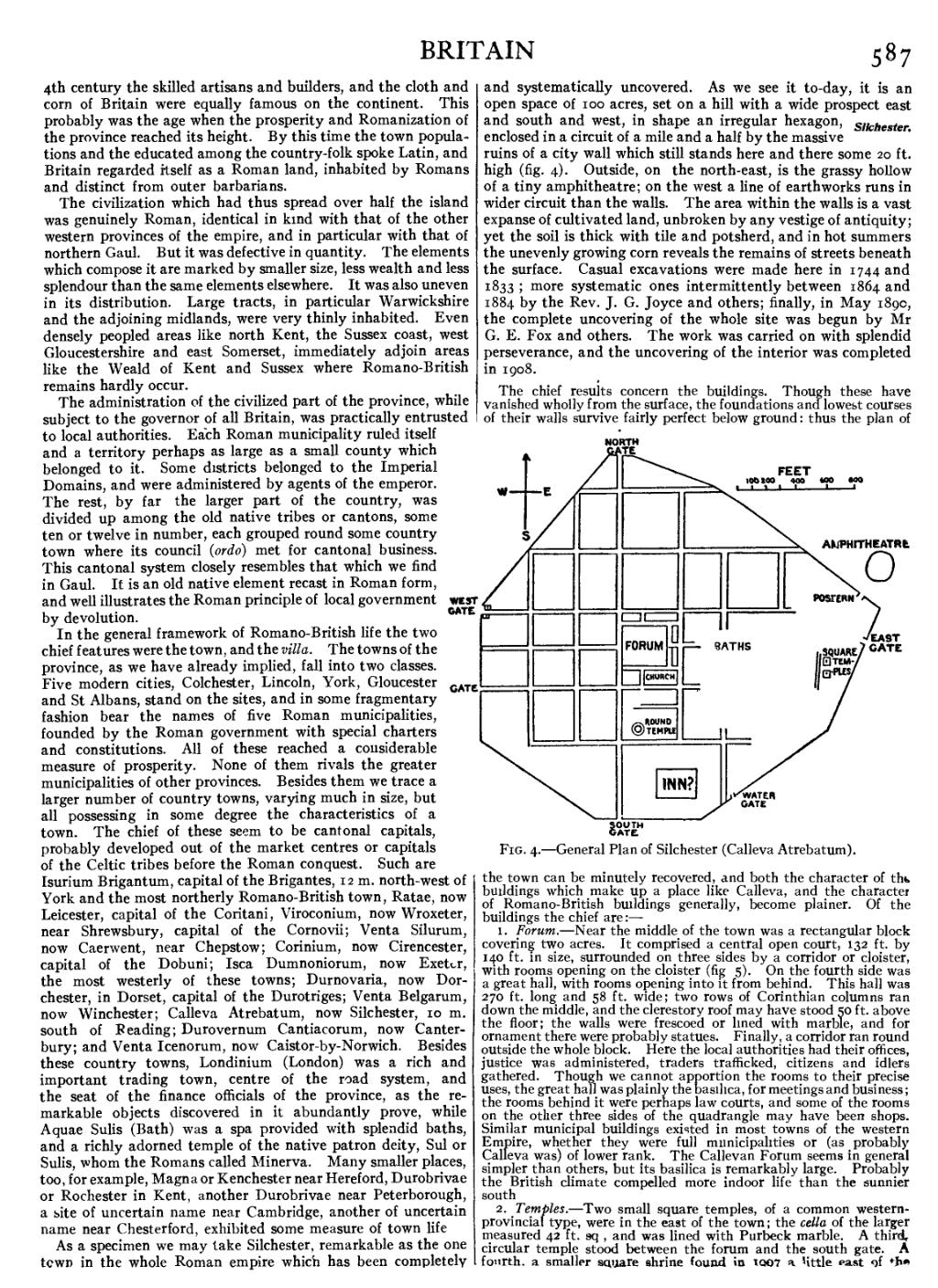

As a specimen we may take Silchester, remarkable as the one town in the whole Roman empire which has been completely and systematically uncovered. As we see it to-day, it is an open space of 100 acres, set on a hill with a wide prospect east and south and west, in shape an Silchester.irregular hexagon, enclosed in a circuit of a mile and a half by the massive ruins of a city wall which still stands here and there some 20 ft. high (fig. 4). Outside, on the north-east, is the grassy hollow of a tiny amphitheatre; on the west a line of earthworks runs in wider circuit than the walls. The area within the walls is a vast expanse of cultivated land, unbroken by any vestige of antiquity; yet the soil is thick with tile and potsherd, and in hot summers the unevenly growing corn reveals the remains of streets beneath the surface. Casual excavations were made here in 1744 and 1833; more systematic ones intermittently between 1864 and 1884 by the Rev. J. G. Joyce and others; finally, in May 1890, the complete uncovering of the whole site was begun by Mr G. E. Fox and others. The work was carried on with splendid perseverance, and the uncovering of the interior was completed in 1908.

The chief results concern the buildings. Though these have vanished wholly from the surface, the foundations and lowest courses of their walls survive fairly perfect below ground: thus the plan of the town can be minutely recovered, and both the character of the buildings which make up a place like Calleva, and the character of Romano-British buildings generally, become plainer. Of the buildings the chief are:—

1. Forum.—Near the middle of the town was a rectangular block covering two acres. It comprised a central open court, 132 ft. by 140 ft. in size, surrounded on three sides by a corridor or cloister, with rooms opening on the cloister (fig. 5). On the fourth side was a great hall, with rooms opening into it from behind. This hall was 270 ft. long and 58 ft. wide; two rows of Corinthian columns ran down the middle, and the clerestory roof may have stood 50 ft. above the floor; the walls were frescoed or lined with marble, and for ornament there were probably statues. Finally, a corridor ran round outside the whole block. Here the local authorities had their offices, justice was administered, traders trafficked, citizens and idlers gathered. Though we cannot apportion the rooms to their precise uses, the great hall was plainly the basilica, for meetings and business; the rooms behind it were perhaps law courts, and some of the rooms on the other three sides of the quadrangle may have been shops. Similar municipal buildings existed in most towns of the western Empire, whether they were full municipalities or (as probably Calleva was) of lower rank. The Callevan Forum seems in general simpler than others, but its basilica is remarkably large. Probably the British climate compelled more indoor life than the sunnier south.

2. Temples.—Two small square temples, of a common western-provincial type, were in the east of the town; the cella of the larger measured 42 ft. sq., and was lined with Purbeck marble. A third, circular temple stood between the forum and the south gate. A fourth, a smaller square shrine found in 1907 a little east of the