new types of design to his own fancy, so that one rarely meets with many repetitions of the same design. One of the most remarkable is the capital in which the leaves are carved as if blown by the wind; the finest example being in Sta Sophia, Thessalonica; those in St Mark’s, Venice (fig. 8) specially attracted Ruskin’s fancy. Others are found in St Apollinare-in-classe, Ravenna. The Thistle and Pine capital is found in St Mark’s, Venice; St Luke’s, Delphi; the mosques of Kairawan and of Ibn Tūlūn, Cairo, in the two latter cases being taken from Byzantine churches. The illustration of the capital in S. Vitale, Ravenna (figs. 9 and 10) shows above it the dosseret required to carry the arch, the springing of which was much wider than the abacus of the capital.

Fig. 9.—Byzantine Capital from the Fig. 10.—Byzantine Capital from

Church of S. Vitale, Ravenna. the Church of S. Vitale, Ravenna.

Fig. 11.—Cushion Capital.Fig. 12.—Romanesque Capitals from the

Cloister of Monreale, near Palermo, Sicily.

The Romanesque and Gothic capitals throughout Europe present the same variety as in the Byzantine and for the same reason, that the artist evolved his conception of the design from the block he was carving, but in these styles it goes further on account of the clustering of columns and piers.

The earliest type of capital in Lombardy and Germany is that which is known as the cushion-cap, in which the lower portion of the cube block has been cut away to meet the circular shaft (fig. 11). These early types were generally painted at first with various geometrical designs, afterwards carved.

In Byzantine capitals, the eagle, the lion and the lamb are occasionally carved, but treated conventionally.

|

|

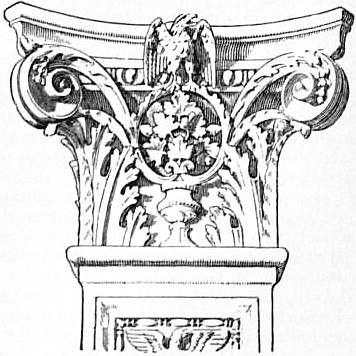

| Fig. 14.—Gothic Capitals from Amiens Cathedral. | Fig.15.—Italian Renaissance Capital from S. Maria dei Miracoli, Venice. |

In the Romanesque and Gothic styles, in addition to birds and beasts, figures are frequently introduced into capitals, those in the Lombard work being rudely carved and verging on the grotesque; later, the sculpture reaches a higher standard; in the cloisters of Monreale (fig. 12) the birds being wonderfully true to nature. In England and France (figs. 13 and 14), the figures introduced into the capitals are sometimes full of character. These capitals, however, are not equal to those of the Early English school, in which the foliage is conventionally treated as if it had been copied from metal work, and is of infinite variety, being found in small village churches as well as in cathedrals.

Reference has only been made to the leading examples of the Roman capitals; in the Renaissance period (fig. 15) the feature became of the greatest importance and its variety almost as great as in the Byzantine and Gothic styles. The pilaster, which