reduced the strong fortress of Bamborough in a week, and in Germany, Franz von Sinkingen’s stronghold of Landstuhl, formerly impregnable on its heights, was ruined in one day by the artillery of Philip of Hesse (1523). Very heavy artillery was used for such work, of course, and against lighter natures, some castles and even fortified country-houses or castellated mansions managed to make a stout stand even as late as the Great Rebellion in England.

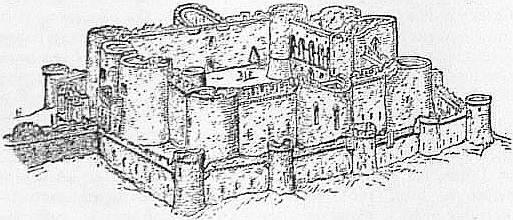

From Clark’s Med. Mil. Arch.

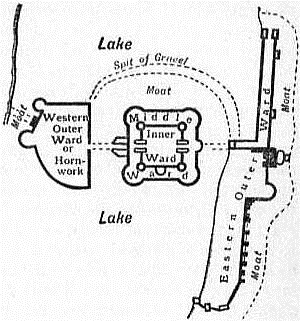

Fig. 9.—Beaumaris Castle: Plan.

The castle thus ceases to be the fortress of small and ill-governing local magnates, and its later history is merged in that of modern fortification. But an interesting transitional type between the medieval stronghold and the modern fortress is found in the coast castles erected by Henry VIII., especially those at Deal, Sandown and Walmer (c. 1540), which played some part in the events of the 17th century, and of which Walmer Castle is still the official residence of the lord warden of the Cinque Ports. Viollet-le-Duc, in his Annals of a Fortress (English trans.), gives a full and interesting account of the repeated renovations of the fortress on his imaginary site in the valley of the Doubs, the construction by Charles the Bold of artillery towers at the angles of the castle, the protection of the masonry by earthen outworks, boulevards and demi-boulevards, and, in the 17th century, the final service of the medieval walls and towers as a pure enceinte de sûreté. Here and there we find old castles serving as forts d’arrêt or block-houses in mountain passes and defiles, and in some few cases, as at Dover, they formed the nucleus of purely military places of arms, but normally the castle falls into ruins, becomes a peaceful mansion, or is merged in the fortifications of the town which has grown up around it. In the Annals of a Fortress the site of the feudal castle is occupied by the citadel of the walled town, for once again, with the development of the middle class and of commerce and industry, the art of the engineer came to be displayed chiefly in the fortification of cities. The baronial “castle” assumes pari passu the form of a mansion, retaining indeed for long some capacity for defence, but in the end losing all military characteristics save a few which survived as ornaments. Examples of such castellated mansions are seen in Wingfield Manor, Derbyshire, and Hurstmonceaux, Sussex, erected in the 15th century, and nearly all older castles which survived were continually improved and altered to serve as residences. (C. F. A.)

Influence of Castles in English History.—Such strongholds as existed in England at the time of the Norman Conquest seem to have offered but little resistance to William the Norman, who, in order effectually to guard against invasions from without as well as to awe his newly-acquired subjects, immediately began to erect castles all over the kingdom, and likewise to repair and augment the old ones. Besides, as he had parcelled out the lands of the English amongst his followers, they, to protect themselves from the resentment of the despoiled natives, built strongholds and castles on their estates, and these were multiplied so rapidly during the troubled reign of King Stephen that the “adulterine” (i.e. unauthorized) castles are said by one writer to have amounted to 1115.

In the first instance, when the interest of the king and of his barons was identical, the former had only retained in his hands the castles in the chief towns of the shires, which were entrusted to his sheriffs or constables. But the great feudal revolts under the Conqueror and his sons showed how formidable an obstacle to the rule of the king was the existence of such fortresses in private hands, while the people hated them from the first for the oppressions connected with their erection and maintenance. It was, therefore, the settled policy of the crown to strengthen the royal castles and increase their number, while jealously keeping in check those of the barons. But in the struggle between Stephen and the empress Maud for the crown, which became largely a war of sieges, the royal power was relaxed and there was an outburst of castle-building, without permission, by the barons. These in many cases acted as petty sovereigns, and such was their tyranny that the native chronicler describes the castles as “filled with devils and evil men.” These excesses paved the way for the pacification at the close of the reign, when it was provided that all unauthorized castles constructed during its course should be destroyed. Henry II., in spite of his power, was warned by the great revolt against him that he must still rely on castles, and the massive keeps of Newcastle and of Dover date from this period.

Under his sons the importance of the chief castles was recognized as so great that the struggle for their control was in the forefront of every contest. When Richard made vast grants at his accession to his brother John, he was careful to reserve the possession of certain castles, and when John rose against the king’s minister, Longchamp, in 1191, the custody of castles was the chief point of dispute throughout their negotiations, and Lincoln was besieged on the king’s behalf, as were Tickhill, Windsor and Marlborough subsequently, while the siege of Nottingham had to be completed by Richard himself on his arrival. To John, in turn, as king, the fall of Château Gaillard meant the loss of Rouen and of Normandy with it, and when he endeavoured to repudiate the newly-granted Great Charter, his first step was to prepare the royal castles against attack and make them his centres of resistance. The barons, who had begun their revolt by besieging that of Northampton, now assailed that of Oxford as well and