abdomen. The upper surface of the elytron is sharply folded inwards at intervals, so as to give rise to a regular series of external longitudinal furrows (striae) and to form a set of supports between the two chitinous layers forming the elytron. The upper surface often shows a number of impressed dots (punctures). Along the sutural border of the elytron, the chitinous lamella forms a tubular space within which are numerous glands. The glands occur in groups, and lead into common ducts which open in several series along the suture. Sometimes the glands are found beneath the disk of the elytron, opening by pores on the surface. The hind-wings, when developed, are characteristic in form, possessing a sub-costal nervure with which the reduced radial nervure usually becomes associated. There are several curved median and cubital nervures and a single anal, but few cross nervures or areolets. The wing, when not in use, is folded both lengthwise and transversely, and doubled up beneath the elytron; to permit the transverse folding, the longitudinal nervures are interrupted.

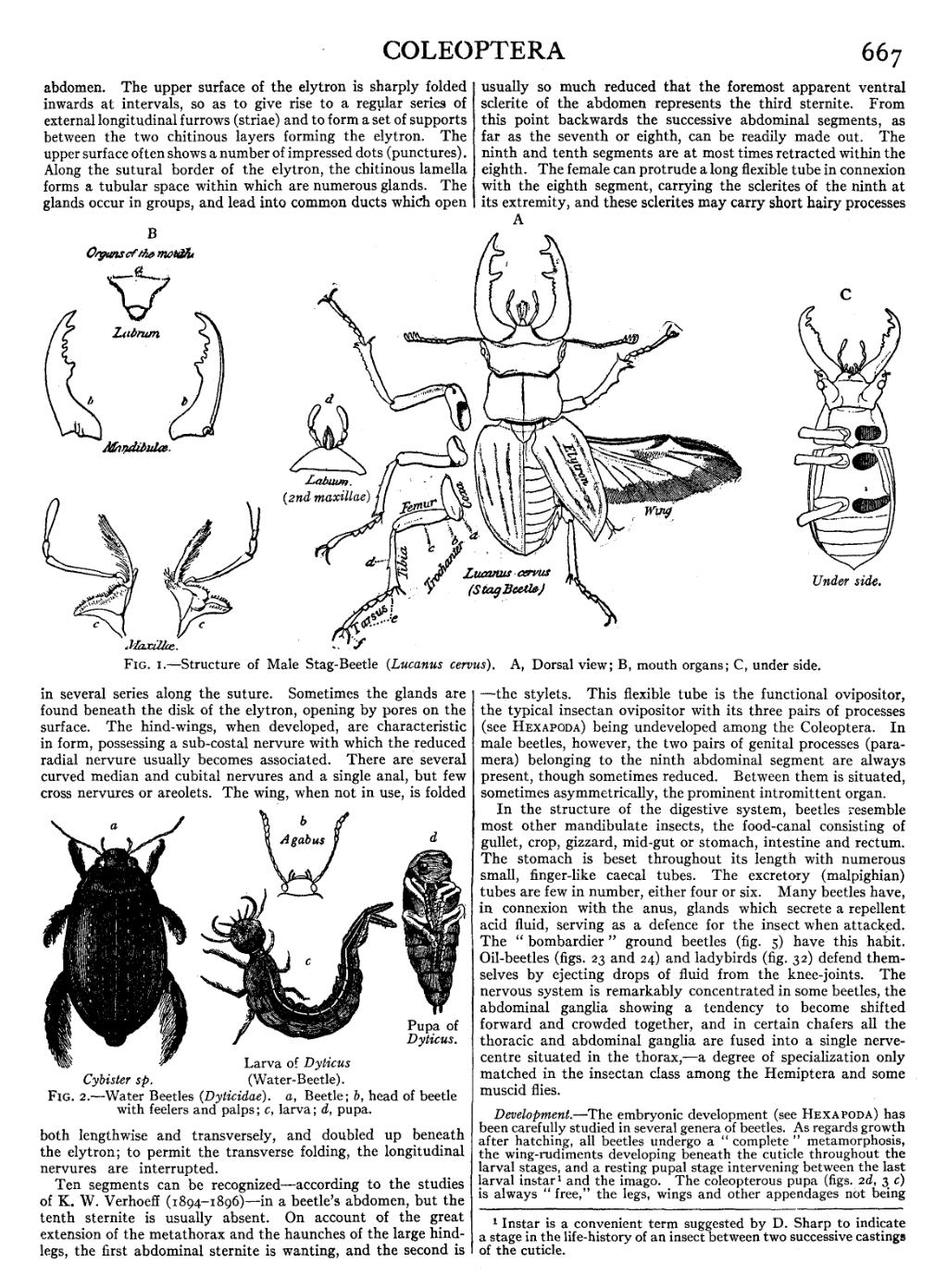

with feelers and palps; c, larva; d, pupa.

Ten segments can be recognized—according to the studies of K. W. Verhoeff (1804–1896)—in a beetle’s abdomen, but the tenth sternite is usually absent. On account of the great extension of the metathorax and the haunches of the large hind-legs, the first abdominal sternite is wanting, and the second is usually so much reduced that the foremost apparent ventral sclerite of the abdomen represents the third sternite. From this point backwards the successive abdominal segments, as far as the seventh or eighth, can be readily made out. The ninth and tenth segments are at most times retracted within the eighth. The female can protrude a long flexible tube in connexion with the eighth segment, carrying the sclerites of the ninth at its extremity, and these sclerites may carry short hairy processes—the stylets. This flexible tube is the functional ovipositor, the typical insectan ovipositor with its three pairs of processes (see Hexapoda) being undeveloped among the Coleoptera. In male beetles, however, the two pairs of genital processes (paramera) belonging to the ninth abdominal segment are always present, though sometimes reduced. Between them is situated, sometimes asymmetrically, the prominent intromittent organ.

In the structure of the digestive system, beetles resemble most other mandibulate insects, the food-canal consisting of gullet, crop, gizzard, mid-gut or stomach, intestine and rectum. The stomach is beset throughout its length with numerous small, finger-like caecal tubes. The excretory (malpighian) tubes are few in number, either four or six. Many beetles have, in connexion with the anus, glands which secrete a repellent acid fluid, serving as a defence for the insect when attacked. The “bombardier” ground beetles (fig. 5) have this habit. Oil-beetles (figs. 23 and 24) and ladybirds (fig. 32) defend themselves by ejecting drops of fluid from the knee-joints. The nervous system is remarkably concentrated in some beetles, the abdominal ganglia showing a tendency to become shifted forward and crowded together, and in certain chafers all the thoracic and abdominal ganglia are fused into a single nerve-centre situated in the thorax,—a degree of specialization only matched in the insectan class among the Hemiptera and some muscid flies.

Development.—The embryonic development (see Hexapoda) has been carefully studied in several genera of beetles. As regards growth after hatching, all beetles undergo a “complete” metamorphosis, the wing-rudiments developing beneath the cuticle throughout the larval stages, and a resting pupal stage intervening between the last larval instar[1] and the imago. The coleopterous pupa (figs. 2d, 3c) is always “free,” the legs, wings and other appendages not being

- ↑ Instar is a convenient term suggested by D. Sharp to indicate a stage in the life-history of an insect between two successive castings of the cuticle.