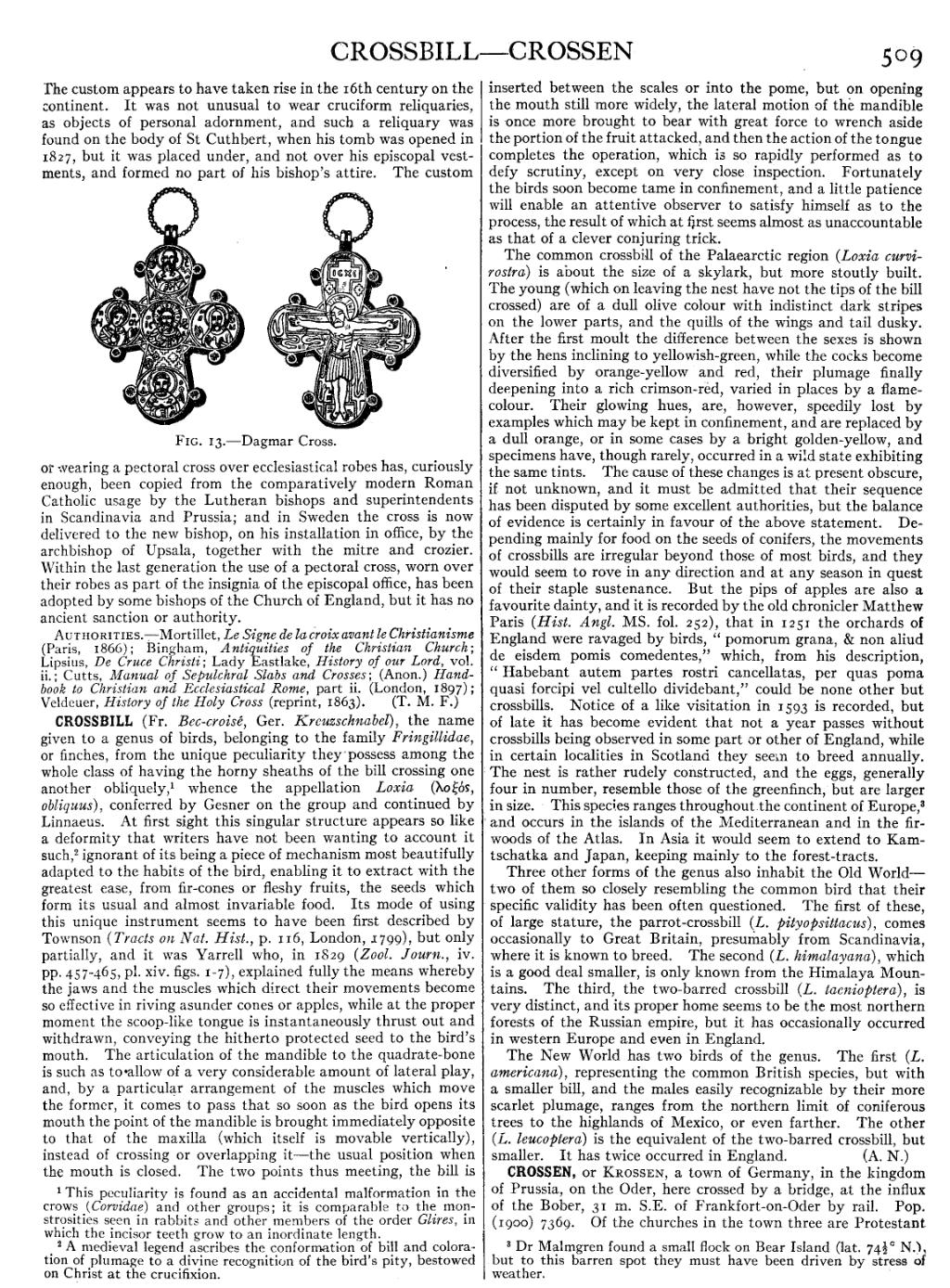

The custom appears to have taken rise in the 16th century on the continent. It was not unusual to wear cruciform reliquaries, as objects of personal adornment, and such a reliquary was found on the body of St Cuthbert, when his tomb was opened in 1827, but it was placed under, and not over his episcopal vestments, and formed no part of his bishop’s attire. The custom of wearing a pectoral cross over ecclesiastical robes has, curiously enough, been copied from the comparatively modern Roman Catholic usage by the Lutheran bishops and superintendents in Scandinavia and Prussia; and in Sweden the cross is now delivered to the new bishop, on his installation in office, by the archbishop of Upsala, together with the mitre and crozier. Within the last generation the use of a pectoral cross, worn over their robes as part of the insignia of the episcopal office, has been adopted by some bishops of the Church of England, but it has no ancient sanction or authority.

|

| Fig. 13.—Dagmar Cross. |

Authorities.—Mortillet, Le Signe de la croix avant le Christianisme (Paris, 1866); Bingham, Antiquities of the Christian Church; Lipsius, De Cruce Christi; Lady Eastlake, History of our Lord, vol. ii.; Cutts, Manual of Sepulchral Slabs and Crosses; (Anon.) Handbook to Christian and Ecclesiastical Rome, part ii. (London, 1897); Veldeuer, History of the Holy Cross (reprint, 1863). (T. M. F.)

CROSSBILL (Fr. Bec-croisé, Ger. Kreuzschnabel), the name

given to a genus of birds, belonging to the family Fringillidae,

or finches, from the unique peculiarity they possess among the

whole class of having the horny sheaths of the bill crossing one

another obliquely,[1] whence the appellation Loxia (λοξός,

obliquus), conferred by Gesner on the group and continued by

Linnaeus. At first sight this singular structure appears so like

a deformity that writers have not been wanting to account it

such,[2] ignorant of its being a piece of mechanism most beautifully

adapted to the habits of the bird, enabling it to extract with the

greatest ease, from fir-cones or fleshy fruits, the seeds which

form its usual and almost invariable food. Its mode of using

this unique instrument seems to have been first described by

Townson (Tracts on Nat. Hist., p. 116, London, 1799), but only

partially, and it was Yarrell who, in 1829 (Zool. Journ., iv.

pp. 457–465, pl. xiv. figs. 1-7), explained fully the means whereby

the jaws and the muscles which direct their movements become

so effective in riving asunder cones or apples, while at the proper

moment the scoop-like tongue is instantaneously thrust out and

withdrawn, conveying the hitherto protected seed to the bird’s

mouth. The articulation of the mandible to the quadrate-bone

is such as to allow of a very considerable amount of lateral play,

and, by a particular arrangement of the muscles which move

the former, it comes to pass that so soon as the bird opens its

mouth the point of the mandible is brought immediately opposite

to that of the maxilla (which itself is movable vertically),

instead of crossing or overlapping it—the usual position when

the mouth is closed. The two points thus meeting, the bill is

inserted between the scales or into the pome, but on opening

the mouth still more widely, the lateral motion of the mandible

is once more brought to bear with great force to wrench aside

the portion of the fruit attacked, and then the action of the tongue

completes the operation, which is so rapidly performed as to

defy scrutiny, except on very close inspection. Fortunately

the birds soon become tame in confinement, and a little patience

will enable an attentive observer to satisfy himself as to the

process, the result of which at first seems almost as unaccountable

as that of a clever conjuring trick.

The common crossbill of the Palaearctic region (Loxia curvirostra) is about the size of a skylark, but more stoutly built. The young (which on leaving the nest have not the tips of the bill crossed) are of a dull olive colour with indistinct dark stripes on the lower parts, and the quills of the wings and tail dusky. After the first moult the difference between the sexes is shown by the hens inclining to yellowish-green, while the cocks become diversified by orange-yellow and red, their plumage finally deepening into a rich crimson-red, varied in places by a flame-colour. Their glowing hues, are, however, speedily lost by examples which may be kept in confinement, and are replaced by a dull orange, or in some cases by a bright golden-yellow, and specimens have, though rarely, occurred in a wild state exhibiting the same tints. The cause of these changes is at present obscure, if not unknown, and it must be admitted that their sequence has been disputed by some excellent authorities, but the balance of evidence is certainly in favour of the above statement. Depending mainly for food on the seeds of conifers, the movements of crossbills are irregular beyond those of most birds, and they would seem to rove in any direction and at any season in quest of their staple sustenance. But the pips of apples are also a favourite dainty, and it is recorded by the old chronicler Matthew Paris (Hist. Angl. MS. fol. 252), that in 1251 the orchards of England were ravaged by birds, “pomorum grana, & non aliud de eisdem pomis comedentes,” which, from his description, “Habebant autem partes rostri cancellatas, per quas poma quasi forcipi vel cultello dividebant,” could be none other but crossbills. Notice of a like visitation in 1593 is recorded, but of late it has become evident that not a year passes without crossbills being observed in some part or other of England, while in certain localities in Scotland they seem to breed annually. The nest is rather rudely constructed, and the eggs, generally four in number, resemble those of the greenfinch, but are larger in size. This species ranges throughout the continent of Europe,[3] and occurs in the islands of the Mediterranean and in the fir-woods of the Atlas. In Asia it would seem to extend to Kamtschatka and Japan, keeping mainly to the forest-tracts.

Three other forms of the genus also inhabit the Old World—two of them so closely resembling the common bird that their specific validity has been often questioned. The first of these, of large stature, the parrot-crossbill (L. pityopsittacus), comes occasionally to Great Britain, presumably from Scandinavia, where it is known to breed. The second (L. himalayana), which is a good deal smaller, is only known from the Himalaya Mountains. The third, the two-barred crossbill (L. taenioptera), is very distinct, and its proper home seems to be the most northern forests of the Russian empire, but it has occasionally occurred in western Europe and even in England.

The New World has two birds of the genus. The first (L. americana), representing the common British species, but with a smaller bill, and the males easily recognizable by their more scarlet plumage, ranges from the northern limit of coniferous trees to the highlands of Mexico, or even farther. The other (L. leucoptera) is the equivalent of the two-barred crossbill, but smaller. It has twice occurred in England. (A. N.)

CROSSEN, or Krossen, a town of Germany, in the kingdom of Prussia, on the Oder, here crossed by a bridge, at the influx of the Bober, 31 m. S.E. of Frankfort-on-Oder by rail. Pop. (1900) 7369. Of the churches in the town three are Protestant

- ↑ This peculiarity is found as an accidental malformation in the crows (Corvidae) and other groups; it is comparable to the monstrosities seen in rabbits and other members of the order Glires, in which the incisor teeth grow to an inordinate length.

- ↑ A medieval legend ascribes the conformation of bill and coloration of plumage to a divine recognition of the bird’s pity, bestowed on Christ at the crucifixion.

- ↑ Dr Malmgren found a small flock on Bear Island (lat. 74½° N.), but to this barren spot they must have been driven by stress of weather.