of gearing, but the idea of providing mechanical connexions between the feet and the wheels was apparently not thought of till later. Pedals with connecting rods working on the rear axle are said to have been applied to a tricycle in 1834 by Kirkpatrick McMillan, a Scottish blacksmith of Keir, Dumfriesshire, and to a draisine by him in 1840, and by a Scottish cooper, Gavin Dalzell, of Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire, about 1845. The draisine thus fitted had wooden wheels, with iron tires, the leading one about 30 in. in diameter and the driving one about 40 in., and thus it formed the prototype, though not the ancestor, of the modern rear-driven safety bicycle.

|

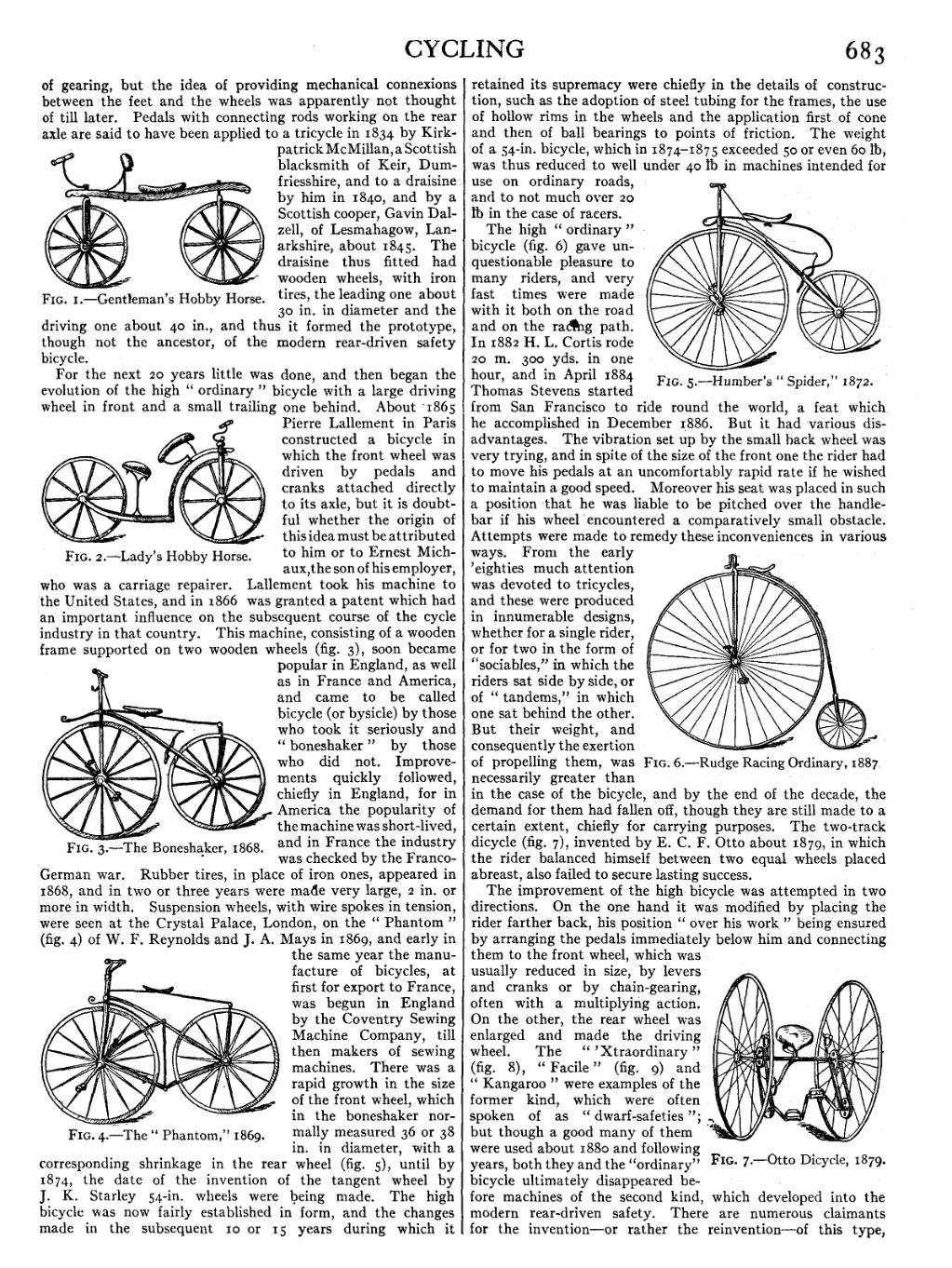

| Fig. 1.—Gentleman’s Hobby Horse. |

|

| Fig. 2.—Lady’s Hobby Horse. |

|

| Fig. 3.—The Boneshaker, 1868. |

|

| Fig. 4.—The “Phantom,” 1869. |

For the next 20 years little was done, and then began the evolution of the high “ordinary” bicycle with a large driving wheel in front and a small trailing one behind. About 1865 Pierre Lallement in Paris constructed a bicycle in which the front wheel was driven by pedals and cranks attached directly to its axle, but it is doubtful whether the origin of this idea must be attributed to him or to Ernest Michaux, the son of his employer, who was a carriage repairer. Lallement took his machine to the United States, and in 1866 was granted a patent which had an important influence on the subsequent course of the cycle industry in that country. This machine, consisting of a wooden frame supported on two wooden wheels (fig. 3), soon became popular in England, as well as in France and America, and came to be called bicycle (or bysicle) by those who took it seriously and “boneshaker” by those who did not. Improvements quickly followed, chiefly in England, for in America the popularity of the machine was short-lived, and in France the industry was checked by the Franco-German war. Rubber tires, in place of iron ones, appeared in 1868, and in two or three years were made very large, 2 in. or more in width. Suspension wheels, with wire spokes in tension, were seen at the Crystal Palace, London, on the “Phantom” (fig. 4) of W. F. Reynolds and J. A. Mays in 1869, and early in the same year the manufacture of bicycles, at first for export to France, was begun in England by the Coventry Sewing Machine Company, till then makers of sewing machines. There was a rapid growth in the size of the front wheel, which in the boneshaker normally measured 36 or 38 in. in diameter, with a corresponding shrinkage in the rear wheel (fig. 5), until by 1874, the date of the invention of the tangent wheel by J. K. Starley 54-in. wheels were being made. The high bicycle was now fairly established in form, and the changes made in the subsequent 10 or 15 years during which it retained its supremacy were chiefly in the details of construction, such as the adoption of steel tubing for the frames, the use of hollow rims in the wheels and the application first of cone and then of ball bearings to points of friction. The weight of a 54-in. bicycle, which in 1874–1875 exceeded 50 or even 60 ℔, was thus reduced to well under 40 ℔ in machines intended for use on ordinary roads, and to not much over 20 ℔ in the case of racers.

|

| Fig. 5.—Humber’s “Spider,” 1872. |

|

| Fig. 6.—Rudge Racing Ordinary, 1887. |

|

| Fig. 7.—Otto Dicycle, 1879. |

The high “ordinary” bicycle (fig. 6) gave unquestionable pleasure to many riders, and very fast times were made with it both on the road and on the racing path. In 1882 H. L. Cortis rode 20 m. 300 yds. in one hour, and in April 1884 Thomas Stevens started from San Francisco to ride round the world, a feat which he accomplished in December 1886. But it had various disadvantages. The vibration set up by the small back wheel was very trying, and in spite of the size of the front one the rider had to move his pedals at an uncomfortably rapid rate if he wished to maintain a good speed. Moreover his seat was placed in such a position that he was liable to be pitched over the handlebar if his wheel encountered a comparatively small obstacle. Attempts were made to remedy these inconveniences in various ways. From the early ’eighties much attention was devoted to tricycles, and these were produced in innumerable designs, whether for a single rider, or for two in the form of “sociables,” in which the riders sat side by side, or of “tandems,” in which one sat behind the other. But their weight, and consequently the exertion of propelling them, was necessarily greater than in the case of the bicycle, and by the end of the decade, the demand for them had fallen off, though they are still made to a certain extent, chiefly for carrying purposes. The two-track dicycle (fig. 7), invented by E. C. F. Otto about 1879, in which the rider balanced himself between two equal wheels placed abreast, also failed to secure lasting success.

The improvement of the high bicycle was attempted in two directions. On the one hand it was modified by placing the rider farther back, his position “over his work” being ensured by arranging the pedals immediately below him and connecting them to the front wheel, which was usually reduced in size, by levers and cranks or by chain-gearing, often with a multiplying action. On the other, the rear wheel was enlarged and made the driving wheel. The “’Xtraordinary” (fig. 8), “Facile” (fig. 9) and “Kangaroo” were examples of the former kind, which were often spoken of as “dwarf-safeties”; but though a good many of them were used about 1880 and following years, both they and the “ordinary” bicycle ultimately disappeared before machines of the second kind, which developed into the modern rear-driven safety. There are numerous claimants for the invention—or rather the reinvention—of this type,