diphtheritic toxin on the nervous tissues has been demonstrated pathologically. There are some who still affect scepticism as to the value of this drug. They cannot be acquainted with the evidence, for if the efficacy of antitoxin in the treatment of diphtheria has not been proved, then neither can the efficacy of any treatment for anything be said to be proved. Prophylactic properties are also claimed for the serum; but protection is necessarily more difficult to demonstrate than cure, and though there is some evidence to support the claim, it has not been fully made out.

Authorities.—Adams, Public Health, vol. vii.; Thorne Thorne, Milroy Lectures (1891); Newsholme, Epidemic Diphtheria; W. R. Smith, Harben Lectures (1899); Murphy, Report to London County Council (1894); Sims Woodhead, Report to Metropolitan Asylums Board (1901).

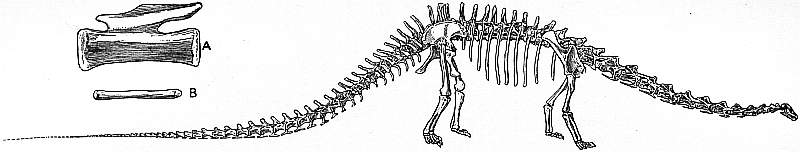

DIPLODOCUS, a gigantic extinct land reptile discovered in rocks of Upper Jurassic age in western North America, the best-known example of a Sauropodous Dinosaur. The first scattered remains of a skeleton were found in 1877 by Prof. S.W. Williston near Cañon City, Colorado; and the tail and hind-limb of this specimen were described in the following year by Prof. O. C. Marsh. He noticed that in the part of the tail which dragged on the ground, each chevron bone below the vertebral column consisted of a pair of bars; and as so peculiar an arrangement for the protection of the artery and vein beneath the tail had not previously been observed in any animal, he proposed the name Diplodocus (“double beam” or “double bar”) for the new reptile, adding the specific name longus in allusion to the elongated shape of the tail vertebrae. In 1884 Prof. Marsh described the head, vertebrae and pelvis of the same skeleton, which is now in the National Museum, Washington. In 1897 the next important specimen, a tail associated with other fragments, apparently of Diplodocus longus, was obtained by the American Museum of Natural History, New York, from Como Bluffs, Wyoming. In 1899–1900 large parts of two skeletons of another species, in a remarkable state of preservation, were disinterred by Messrs J. L. Wortman, O. A. Peterson and J. B. Hatcher in Sheep Creek, Albany county, Wyo., and these are now exhibited with minor discoveries in the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburg. There are also other specimens in New York, Chicago and the University of Wyoming. In 1901 Mr J. B. Hatcher studied the new species at Pittsburg, named it Diplodocus carnegii, and published the first restored sketch of a complete skeleton. Shortly afterwards plaster casts of the finest specimens were prepared under the direction of Mr J. B. Hatcher and Dr W. J. Holland, and these were skilfully combined to form the cast of a completely reconstructed skeleton, which was presented to the British Museum by Andrew Carnegie in 1905. This reconstruction is based primarily on a well-preserved chain of vertebrae, extending from the second cervical to the twelfth caudal, associated with the ribs, pelvis and several limb-bones. The tail is completed from two other specimens in the Carnegie Museum, having caudals 13 to 36 and 37 to 73 respectively in apparently unbroken series. Prof. Marsh’s specimen in Washington supplied the greater part of the skull; and the fore-foot is copied from a specimen in New York.

|

| Reconstructed Skeleton of Diplodocus carnegii, Hatcher, about one-hundredth natural size. A and B, Caudal Vertebrae Nos. 36 and 70 of the same are about one-quarter natural size. |

The cast of the reconstructed skeleton of Diplodocus carnegii measures 84 ft. in length and 12 ft. 9 in. in maximum height at the hind-limbs. It displays the elongated neck and tail and the relatively small head so characteristic of the Sauropodous Dinosaurs. The skull is inclined to the axis of the neck, denoting a browsing animal; while the feeble blunt teeth and flat expanded snout suggest feeding among succulent water-weeds. The large narial opening at the highest point of the head probably indicates an aquatic mode of life, and there seems to have been a soft valve to close the nostrils when under water. The diminutive brain-cavity, scarcely large enough to contain a walnut, is noteworthy. There are 104 vertebrae, namely, 15 in the neck, 11 in the back, 5 in the sacrum and 73 in the tail. The presacral vertebrae are of remarkably light construction, the plates and struts of bone being arranged to give the greatest strength with the least weight. The end of the tail is a flexible lash, which would probably be used as a weapon, like the tail of some existing lizards. The feet, notwithstanding the weight they had to support, are as unsymmetrical as those of a crocodile, with claws only on the three inner toes. There is no external armour.

See O. C. Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci. ser. 3, vol. xvi. (1878), p. 414, pl. viii., and loc. cit. vol. xxvii. (1884), p. 161, pls. iii., iv.; H. F. Osborn, Mem. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. vol. i. pt. v. (1899); J. B. Hatcher, Mem. Carnegie Mus. vol. i. No. 1 (1901), and vol. ii. No. 1 (1903); W. J. Holland, Mem. Carnegie Mus. vol. ii. No. 6 (1906). (A. S. Wo.)

DIPLOMACY (Fr. diplomatie), the art of conducting international negotiations. The word, borrowed from the French, has the same derivation as Diplomatic (q.v.), and, according to the New English Dictionary, was first used in England so late as 1796 by Burke. Yet there is no other word in the English language that could supply its exact sense. The need for such a term was indeed not felt; for what we know as diplomacy was long regarded, partly as falling under the Jus gentium or international law, partly as a kind of activity morally somewhat suspect and incapable of being brought under any system. Moreover, though in a certain sense it is as old as history, diplomacy as a uniform system, based upon generally recognized rules and directed by a diplomatic hierarchy having a fixed international status, is of quite modern growth even in Europe. It was finally established only at the congresses of Vienna (1815) and Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), while its effective extension to the great monarchies of the East, beyond the bounds of European civilization, was comparatively an affair of yesterday. So late as 1876 it was possible for the