their bodies with oil, and put wool, saturated with oil, in their ears. Others hold in their mouth a piece of sponge soaked in oil, which they renew every time they descend. It is doubtful, however, whether these expedients are beneficial. The men who dive in this primitive fashion take with them a flat stone with a hole in the centre; to this is attached a rope, which is secured to the diving boat and serves to guide them to particular spots below. When the diver reaches the sea bottom he tears off as much sponge within reach as possible, or picks up pearl shells, as the case may be, and then pulls the rope to indicate to the man in the boat that he wishes to be hauled up. But so exhausting is the work, and so severe the strain on the system, that, after a number of dives in deep water, the men often become insensible, and blood sometimes bursts from nose, ears and mouth.

Early Diving Appliances.—The earliest mention of any appliance for assisting divers is by Aristotle, who says that divers are sometimes provided with instruments for respiration through which they can draw air from above the water and which thus enable them to remain a long time under the sea (De Part. Anim. 2, 16), and also that divers breathe by letting down a metallic vessel which does not get filled with water but retains the air within it (Problem. 32, 5). It is also recorded that Alexander the Great made a descent into the sea in a machine called a colimpha, which had the power of keeping a man dry, and at the same time of admitting light. Pliny also speaks of divers engaged in the strategy of ancient warfare, who drew air through a tube, one end of which they carried in their mouths, whilst the other end was made to float on the surface of the water. Roger Bacon in 1240, too, is supposed to have invented a contrivance for enabling men to work under water; and in Vegetius’s De Re Militari (editions of 1511 and 1532, the latter in the British Museum) is an engraving representing a diver wearing a tight-fitting helmet to which is attached a long leathern pipe leading to the surface, where its open end is kept afloat by means of a bladder. This method of obtaining air during subaqueous operations was probably suggested by the action of the elephant when swimming; the animal instinctively elevates its trunk so that the end is above the surface of the water, and thus is enabled to take in fresh air at every inspiration.

A certain Repton invented “water armour” in the year 1617, but when tried it was found to be useless. G. A. Borelli in the year 1679 invented an apparatus which enabled persons to go to a certain depth under water, and he is credited with being the first to introduce means of forcing air down to the diver. For this purpose he used a large pair of bellows. John Lethbridge, a Devonshire man, in the year 1715 contrived “a watertight leather case for enclosing the person.” This leather case held about half a hogshead of air, and was so adapted as to give free play to arms and legs, so that the wearer could walk on the sea bottom, examine a sunken vessel and salve her cargo, returning to the surface when his supply of air was getting exhausted. It is said that Lethbridge made a considerable fortune by his invention. The next contrivance worthy of mention, and most nearly resembling the modern diving-dress, was an apparatus invented by Kleingert, of Breslau, in 1798. This consisted of an egg-ended metallic cylinder enveloping the head and the body to the hips. The diver was encased first of all in a leather jacket having tight-fitting arms, and in leather drawers with tight-fitting legs. To these the cylinder was fastened in such a way as to render the whole equipment airtight. The air supply was drawn through a pipe which was connected with the mouth of the diver by an ivory mouthpiece, the surface end being held above water after the manner mentioned in Vegetius, viz. by means of a floating bladder attached to it. The foul air escaped through another pipe held in a similar manner above the surface of the water, inhalation being performed by the mouth and exhalation by the nose, the act of inhalation causing the chest to expand and so to expel the vitiated air through the escape pipe. The diver was weighted when going under water, and when he wished to ascend he released one of his weights, and attached it to a rope which he held, and it was afterwards hauled up.

Modern Apparatus.—This, or equally cumbersome apparatus, was the only diving gear in use up till 1819, in which year Augustus Siebe (the founder of the firm of Siebe, Gorman & Co.), invented his “open” dress, worked in conjunction with an air force pump. This dress consisted of a metal helmet and shoulder-plate attached to a watertight jacket, under which, fitting more closely to the body, were worn trousers, or rather a combination suit reaching to the armpits. The helmet was fitted with an air inlet valve, to which one end of a flexible tube was attached, the other end being connected at the surface with a pump which supplied the diver with a constant stream of fresh air. The air, which kept the water well down, forced its way between the jacket and the under-garment, and escaped to the surface on exactly the same principle as that of the diving bell; hence the term “open” as applied to this dress.

Although most excellent work was accomplished with this dress—work which could not be attempted before its introduction—it was still far from perfect. It was absolutely necessary for the diver to maintain an upright, or but very slightly stooping, position whilst under water; if he stumbled and fell, the water filled his dress, and, unless quickly brought to the surface, he was in danger of being drowned. To overcome this and other defects, Siebe carried out a large number of experiments extending over several years, which culminated, in the year 1830, in the introduction of his “close” dress in combination with a helmet fitted with air inlet and regulating outlet valves.

Though, of course, vast improvements have been introduced since Siebe’s death, in 1872, the fact remains that his principle is in universal use to this day. The submarine work which it has been instrumental in accomplishing is incalculable. But some idea of the importance of the invention may be gathered from the fact that diving apparatus on Siebe’s principle is universally used to-day in harbour, dock, pier and breakwater construction, in the pearl and sponge fisheries, in recovering sunken ships, cargo and treasure, and that every ship in the British navy and in most foreign navies carries one set or more of diving apparatus.

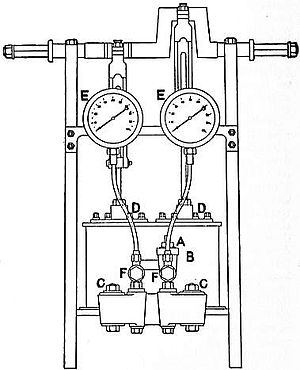

A modern set of diving apparatus consists essentially of six parts:—(1) an air pump, (2) a helmet with breastplate, (3) a diving dress, (4) a pair of heavily weighted boots, (5) a pair of back and chest weights, (6) a flexible non-collapsible air tube.