for enrichment, can only be conjectured. The peplos or woven

cloth made every fifth year to cover or shade the statue of

Athena in the Parthenon at Athens, and carried at the Panathenaic

festival,[1] was ornamented with the battles of the gods

and giants. The late Dr J. H. Middleton thought that very

possibly most of the elaborate work upon these peploi was done

by the needle. That true embroidery, in the modern sense—the

decoration by means of the needle of a finished woven

material—was practised among the ancient Greeks, has been

demonstrated by the finding of some textile fragments in graves

in the Crimea; these are now in the Hermitage at St Petersburg.

One of them, of purple woollen material, from a tomb assigned

to the 4th century B.C., is embroidered in wools of different

colours with a man on horseback, honeysuckle ornament and

tendrils. Another woollen piece, attributed to the following

century, has a stem and arrow-head leaves worked in gold

thread.[2]

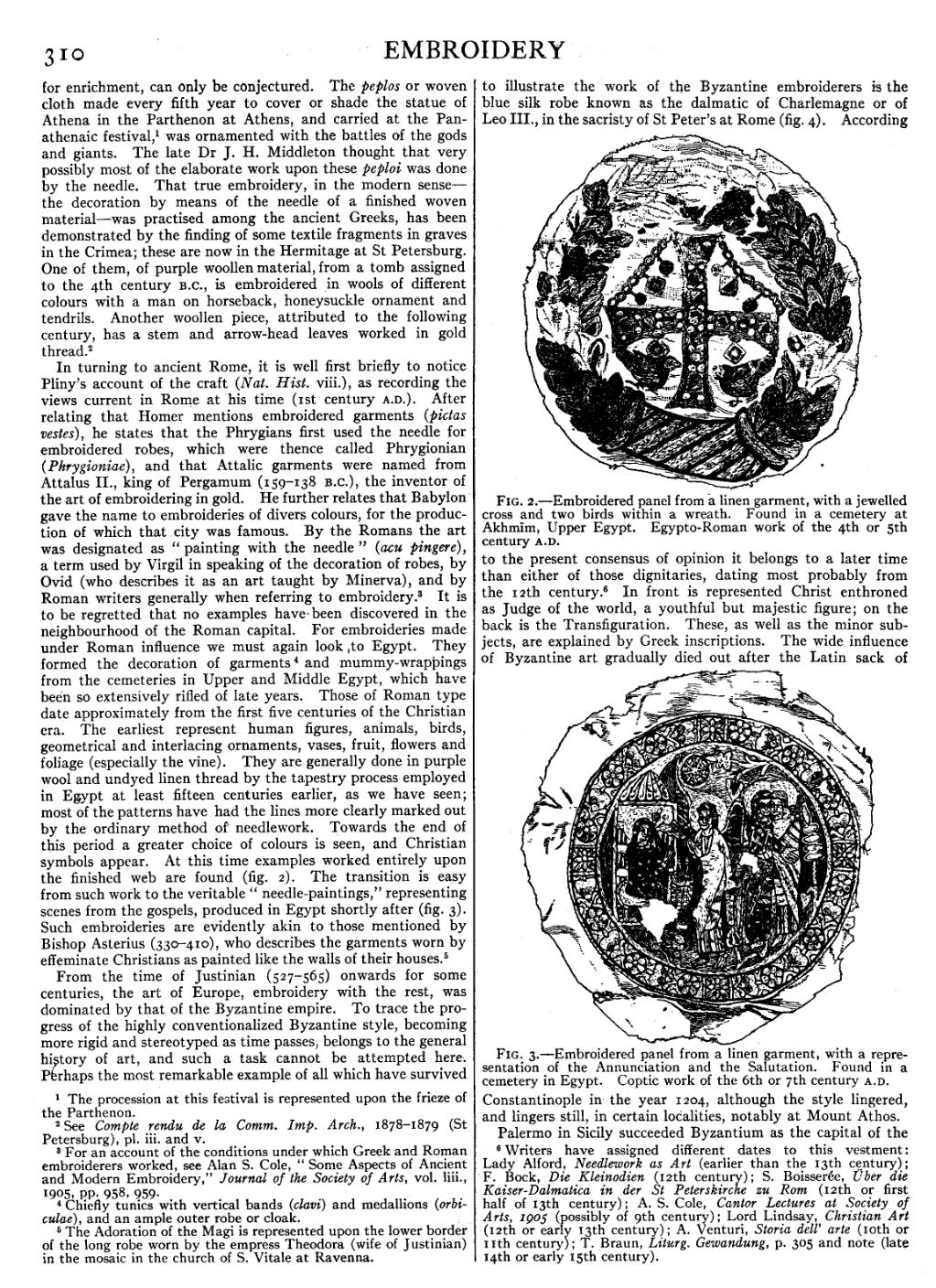

In turning to ancient Rome, it is well first briefly to notice Pliny’s account of the craft (Nat. Hist. viii.), as recording the views current in Rome at his time (1st century A.D.). After relating that Homer mentions embroidered garments (pictas vestes), he states that the Phrygians first used the needle for embroidered robes, which were thence called Phrygionian (Phrygioniae), and that Attalic garments were named from Attalus II., king of Pergamum (159–138 B.C.), the inventor of the art of embroidering in gold. He further relates that Babylon gave the name to embroideries of divers colours, for the production of which that city was famous. By the Romans the art was designated as “painting with the needle” (acu pingere), a term used by Virgil in speaking of the decoration of robes, by Ovid (who describes it as an art taught by Minerva), and by Roman writers generally when referring to embroidery.[3] It is to be regretted that no examples have been discovered in the neighbourhood of the Roman capital. For embroideries made under Roman influence we must again look to Egypt. They formed the decoration of garments[4] and mummy-wrappings from the cemeteries in Upper and Middle Egypt, which have been so extensively rifled of late years. Those of Roman type date approximately from the first five centuries of the Christian era. The earliest represent human figures, animals, birds, geometrical and interlacing ornaments, vases, fruit, flowers and foliage (especially the vine). They are generally done in purple wool and undyed linen thread by the tapestry process employed in Egypt at least fifteen centuries earlier, as we have seen; most of the patterns have had the lines more clearly marked out by the ordinary method of needlework. Towards the end of this period a greater choice of colours is seen, and Christian symbols appear. At this time examples worked entirely upon the finished web are found (fig. 2). The transition is easy from such work to the veritable “needle-paintings,” representing scenes from the gospels, produced in Egypt shortly after (fig. 3). Such embroideries are evidently akin to those mentioned by Bishop Asterius (330–410), who describes the garments worn by effeminate Christians as painted like the walls of their houses.[5]

From the time of Justinian (527–565) onwards for some centuries, the art of Europe, embroidery with the rest, was dominated by that of the Byzantine empire. To trace the progress of the highly conventionalized Byzantine style, becoming more rigid and stereotyped as time passes, belongs to the general history of art, and such a task cannot be attempted here. Perhaps the most remarkable example of all which have survived to illustrate the work of the Byzantine embroiderers is the blue silk robe known as the dalmatic of Charlemagne or of Leo III., in the sacristy of St Peter’s at Rome (fig. 4). According to the present consensus of opinion it belongs to a later time than either of those dignitaries, dating most probably from the 12th century.[6] In front is represented Christ enthroned as Judge of the world, a youthful but majestic figure; on the back is the Transfiguration. These, as well as the minor subjects, are explained by Greek inscriptions. The wide influence of Byzantine art gradually died out after the Latin sack of Constantinople in the year 1204, although the style lingered, and lingers still, in certain localities, notably at Mount Athos.

Palermo in Sicily succeeded Byzantium as the capital of the

- ↑ The procession at this festival is represented upon the frieze of the Parthenon.

- ↑ See Compte rendu de la Comm. Imp. Arch., 1878–1879 (St Petersburg), pl. iii. and v.

- ↑ For an account of the conditions under which Greek and Roman embroiderers worked, see Alan S. Cole, “Some Aspects of Ancient and Modern Embroidery,” Journal of the Society of Arts, vol. liii., 1905, pp. 958, 959.

- ↑ Chiefly tunics with vertical bands (clavi) and medallions (orbiculae), and an ample outer robe or cloak.

- ↑ The Adoration of the Magi is represented upon the lower border of the long robe worn by the empress Theodora (wife of Justinian) in the mosaic in the church of S. Vitale at Ravenna.

- ↑ Writers have assigned different dates to this vestment: Lady Alford, Needlework as Art (earlier than the 13th century); F. Bock, Die Kleinodien (12th century); S. Boisserée, Über die Kaiser-Dalmatica in der St Peterskirche zu Rom (12th or first half of 13th century); A. S. Cole, Cantor Lectures at Society of Arts, 1905 (possibly of 9th century); Lord Lindsay, Christian Art (12th or early 13th century); A. Venturi, Storia dell’ arte (10th or 11th century); T. Braun, Liturg. Gewandung, p. 305 and note (late 14th or early 15th century).