condition. Thus, taking the effective hardness of sapphire as 100, Dr J. Lawrence Smith found that the emery of Samos with 70.10% of alumina had a corresponding hardness of 56; that of Naxos, with 68.53 of Al2O3, a hardness of 46; and that of Gumach with 77.82 of Al2O3, a hardness of 47.

Emery has been worked from a very remote period in the Isle of Naxos, one of the Cyclades, whence the stone was called naxium by Pliny and other Roman writers. The mineral occurs as loose blocks and as lenticular masses or irregular beds in granular limestone, associated with crystalline schists. The Naxos emery has been described by Professor G. Tschermak. From a chemical analysis of a sample it has been calculated that the emery contained 52.4% of corundum, 32.1 of magnetite, 11.5 of tourmaline, 2 of muscovite and 2 of margarite.

Important deposits of corundum were discovered in Asia Minor by J. Lawrence Smith, when investigating Turkish mineral resources about 1847. The chief sources of emery there are Gumach Dagh, a mountain about 12 m. E. of Ephesus; Kula, near Ala-shehr; and the mines in the hills between Thyra and Cosbonnar, south of Smyrna. The occurrence is similar to that in Naxos. The emery is found as detached blocks in a reddish soil, and as rounded masses embedded in a crystalline limestone associated with mica-schist, gneiss and granite. The proportion of corundum in this emery is said to vary from 37 to 57%. Emery is worked at several localities in the United States, especially near Chester, in Hampden county, Mass., where it is associated with peridotites. The corundum and magnetite are regarded by Dr J. H. Pratt as basic segregations from an igneous magma. The deposits were discovered by H. S. Lucas in 1864.

The hardness and toughness of emery render it difficult to work, but it may be extracted from the rock by blasting in holes bored with diamond drills. In the East fire-setting is employed. The emery after being broken up is carefully picked by hand, and then ground or stamped, and separated into grades by wire sieves. The higher grades are prepared by washing and eleutriation, the finest being known as “flour of emery.” A very fine emery dust is collected in the stamping room, where it is deposited after floating in the air. The fine powder is used by lapidaries and plate-glass manufacturers. Emery-wheels are made by consolidating the powdered mineral with an agglutinating medium like shellac or silicate of soda or vulcanized india-rubber. Such wheels are not only used by dentists and lapidaries but are employed on a large scale in mechanical workshops for grinding, shaping and polishing steel. Emery-sticks, emery-cloth and emery-paper are made by coating the several materials with powdered emery mixed with glue, or other adhesive media. (See Corundum.) (F. W. R.*)

EMETICS (from Gr. ἐμετικός, causing vomit), the term

given to substances which are administered for the purpose

of producing vomiting. It is customary to divide emetics into

two classes, those which produce their effect by acting on the

vomiting centre in the medulla, and those which act directly

on the stomach itself. There is considerable confusion in the

nomenclature of these two divisions, but all are agreed in calling

the former class central emetics, and the latter gastric. The

gastric emetics in common use are alum, ammonium carbonate,

zinc sulphate, sodium chloride (common salt), mustard and

warm water. Copper sulphate has been purposely omitted

from this list, since unless it produces vomiting very shortly

after administration, being itself a violent gastro-intestinal

irritant, some other emetic must promptly be administered.

The central emetics are apomorphine, tartar emetic, ipecacuanha,

senega and squill. Of these tartar emetic and ipecacuanha

come under both heads: when taken by the mouth they act

as gastric emetics before absorption into the blood, and later

produce a further and more vigorous effect by stimulation of

the medullary centre. It must be remembered, however, that,

valuable though these drugs are, their action is accompanied

by so much depression, they should never be administered

except under medical advice.

Emetics have two main uses: that of emptying the stomach, especially in cases of poisoning, and that of expelling the contents of the air passages, more especially in children before they have learnt or have the strength to expectorate. Where a physician is in attendance, the first of these uses is nearly always replaced by lavage of the stomach, whereby any subsequent depression is avoided. Emetics still have their place, however, in the treatment of bronchitis, laryngitis and diphtheria in children, as they aid in the expulsion of the morbid products. Occasionally also they are administered when a foreign body has got into the larynx. Their use is contra-indicated in the case of anyone suffering from aneurism, hernia or arterio-sclerosis, or where there is any tendency to haemorrhage.

EMEU, evidently from the Port. Ema,[1] a name which has in

turn been applied to each of the earlier-known forms of Ratite

birds, but has finally settled upon that which inhabits Australia,

though, up to the close of the 18th century, it was given by most

authors to the bird now commonly called cassowary—this last

word being a corrupted form of the Malayan Suwari (see Crawfurd,

Gramm. and Dict. Malay Language, ii. pp. 178 and 25),

apparently first printed as Casoaris by Bontius in 1658 (Hist.

nat. et med. Ind. Orient. p. 71).

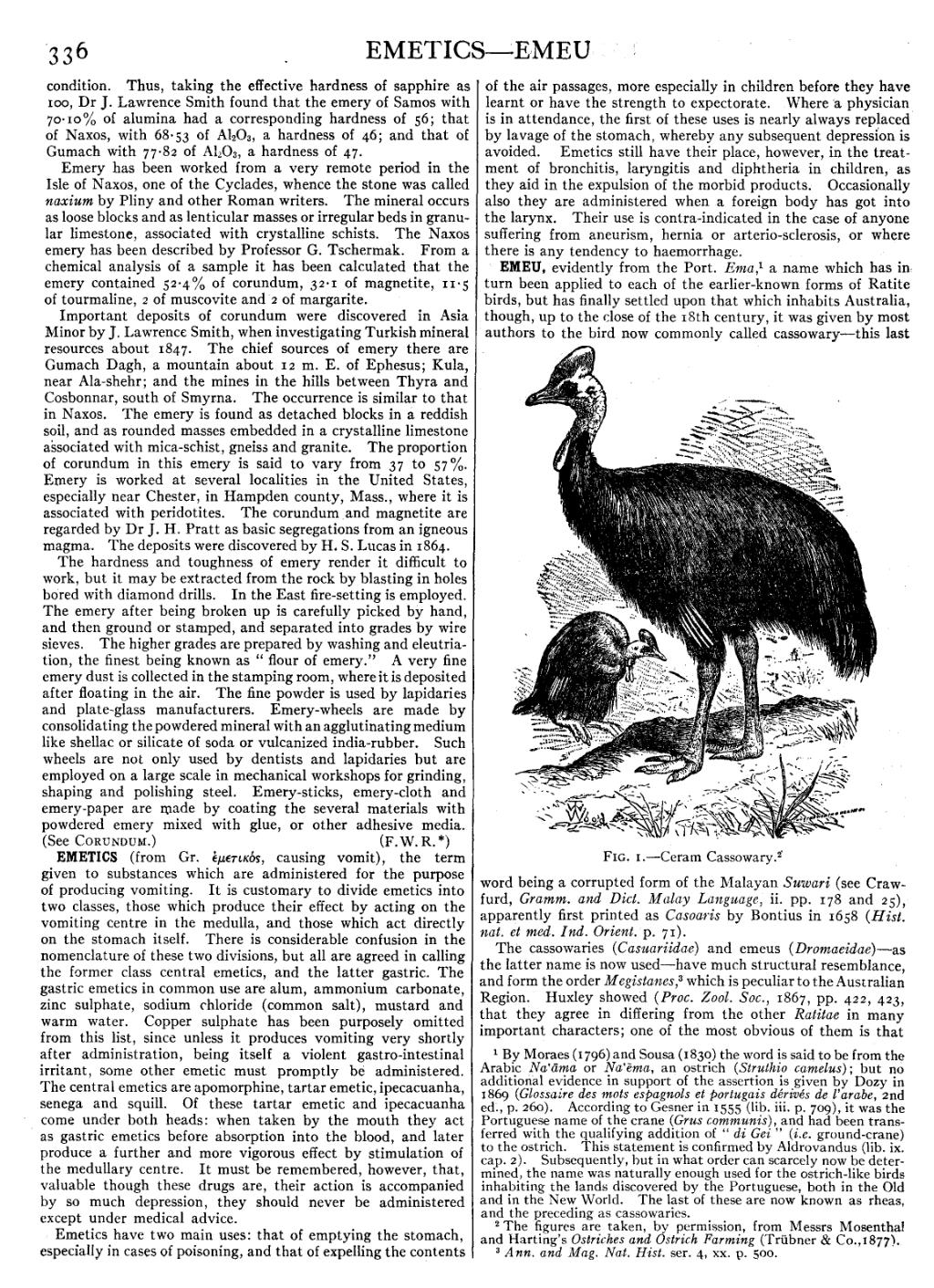

Fig. 1.—Ceram Cassowary.[2]

The cassowaries (Casuariidae) and emeus (Dromaeidae)—as the latter name is now used—have much structural resemblance, and form the order Megistanes,[3] which is peculiar to the Australian Region. Huxley showed (Proc. Zool. Soc., 1867, pp. 422, 423,) that they agree in differing from the other Ratitae in many important characters; one of the most obvious of them is that

- ↑ By Moraes (1796) and Sousa (1830) the word is said to be from the Arabic Naʽāma or Naʽēma, an ostrich (Struthio camelus); but no additional evidence in support of the assertion is given by Dozy in 1869 (Glossaire des mots espagnols et portugais dérivés de l’arabe, 2nd ed., p. 260). According to Gesner in 1555 (lib. iii. p. 709), it was the Portuguese name of the crane (Grus communis), and had been transferred with the qualifying addition of “di Gei ” (i.e. ground-crane) to the ostrich. This statement is confirmed by Aldrovandus (lib. ix. cap. 2). Subsequently, but in what order can scarcely now be determined, the name was naturally enough used for the ostrich-like birds inhabiting the lands discovered by the Portuguese, both in the Old and in the New World. The last of these are now known as rheas, and the preceding as cassowaries.

- ↑ The figures are taken, by permission, from Messrs Mosenthal and Harting’s Ostriches and Ostrich Farming (Trübner & Co., 1877).

- ↑ Ann. and Mag. Nat. Hist. ser. 4, xx. p. 500.