“intermittent parasites,” because when gorged they leave their

hosts, fishes or frogs, and swim about in freedom for a considerable

period. The long-known Argulus (O. F. Müller) has

the second maxillae transformed into suckers, but in Dolops

(Audouin, 1837) (fig. 1), the name of which supersedes the more

familiar Gyropeltis (Heller, 1857), these effect attachment by

ending in strong hooks (Bouvier, 1897). A third genus, Chonopeltis

(Thiele, 1900), has suckers, but has lost its first antennae,

at least in the female.

Ostracoda.—The body, seldom in any way segmented, is wholly encased in a bivalved shell, the caudal part strongly inflexed, and almost always ending in a furca. The limbs, including antennae and mouth organs, never exceed seven definite pairs. The first antennae never have more than eight joints. The young usually pass through several stages of development after leaving the egg, and this commonly after, even long after, the egg has left the maternal shell. Parthenogenesis is frequent.

The four tribes instituted by Sars in 1865 were reduced to two by G. W. Müller in 1894, the Myodocopa, which almost always have a heart, and the Podocopa, which have none.

Myodocopa.—These have the furcal branches broad, lamellar, with at least three pairs of strong spines or ungues. Almost always the shell has a rostral sinus. Müller divides the tribe into three families, Cypridinidae, Halocypridae, and the heartless Polycopidae, which constituted the tribe Cladocopa of Sars. From the first of these Brady and Norman distinguish the Asteropidae (fig. 3), remarkable for seven pairs of long branchial leaves which fold over the hinder extremity of the animal, and the Sarsiellidae, still somewhat obscure, besides adding the Rutidermatidae, knowledge of which is based on skilful maceration of minute and long-dried specimens. The Halocypridae are destitute of compound lateral eyes, and have the sexual orifice unsymmetrically placed.

Podocopa.—In these the furcal branches are linear or rudimentary, the shell is without rostral sinus, and, besides distinguishing characters of the second antennae, they have always a branchial plate well developed on the first maxillae, which is inconstant in the other tribe. There are five families: (a) Cyprididae (? including Cypridopsidae of Brady and Norman). In some of the genera parthenogenetic propagation is carried to such an extent that of the familiar Cypris it is said, “until quite lately males in this genus were unknown; and up to the present time no male has been found in the British Islands” (Brady and Norman, 1896). On the other hand, the ejaculatory duct with its verticillate sac in the male of Cypris and other genera is a feature scarcely less remarkable. (b) Bairdiidae, which have the valves smooth, with the hinge untoothed. (c) Cytheridae (? including Paradoxostomatidae of Brady and Norman), in which the valves are usually sculptured, with toothed hinge. Of this family the members are almost exclusively marine, but Limnicythere is found in fresh water, and Xestoleberis bromeliarum (Fritz Müller) lives in the water that collects among the leaves of Bromelias, plants allied to the pine-apples. (d) Darwinulidae, including the single species Darwinula stevensoni, Brady and Robertson, described as “perhaps the most characteristic Entomostracan of the East Anglian Fen District.” (e) Cytherellidae, which, unlike the Ostracoda in general, have the hinder part of the body segmented, at least ten segments being distinguishable in the female. They have the valves broad at both ends, and were placed by Sars in a separate tribe, called Platycopa.

The range in time of the Ostracoda is so extended that, in G. W. Müller’s opinion, their separation into the families now living may have already taken place in the Cambrian period. Their range in space, including carriage by birds, may be coextensive with the distribution of water, but it is not known what height of temperature or how much chemical adulteration of the water they can sustain, how far they can penetrate underground, nor what are the limits of their activity between the floor and the surface of aquatic expanses, fresh or saline. In individual size they have never been important, and of living forms the largest is one of recent discovery, Crossophorus africanus, a Cypridinid about three-fifths of an inch (15.5 mm.) long; but a length of one or two millimetres is more common, and it may descend to the seventy-fifth of an inch. By multitude they have been, and still are, extremely important.

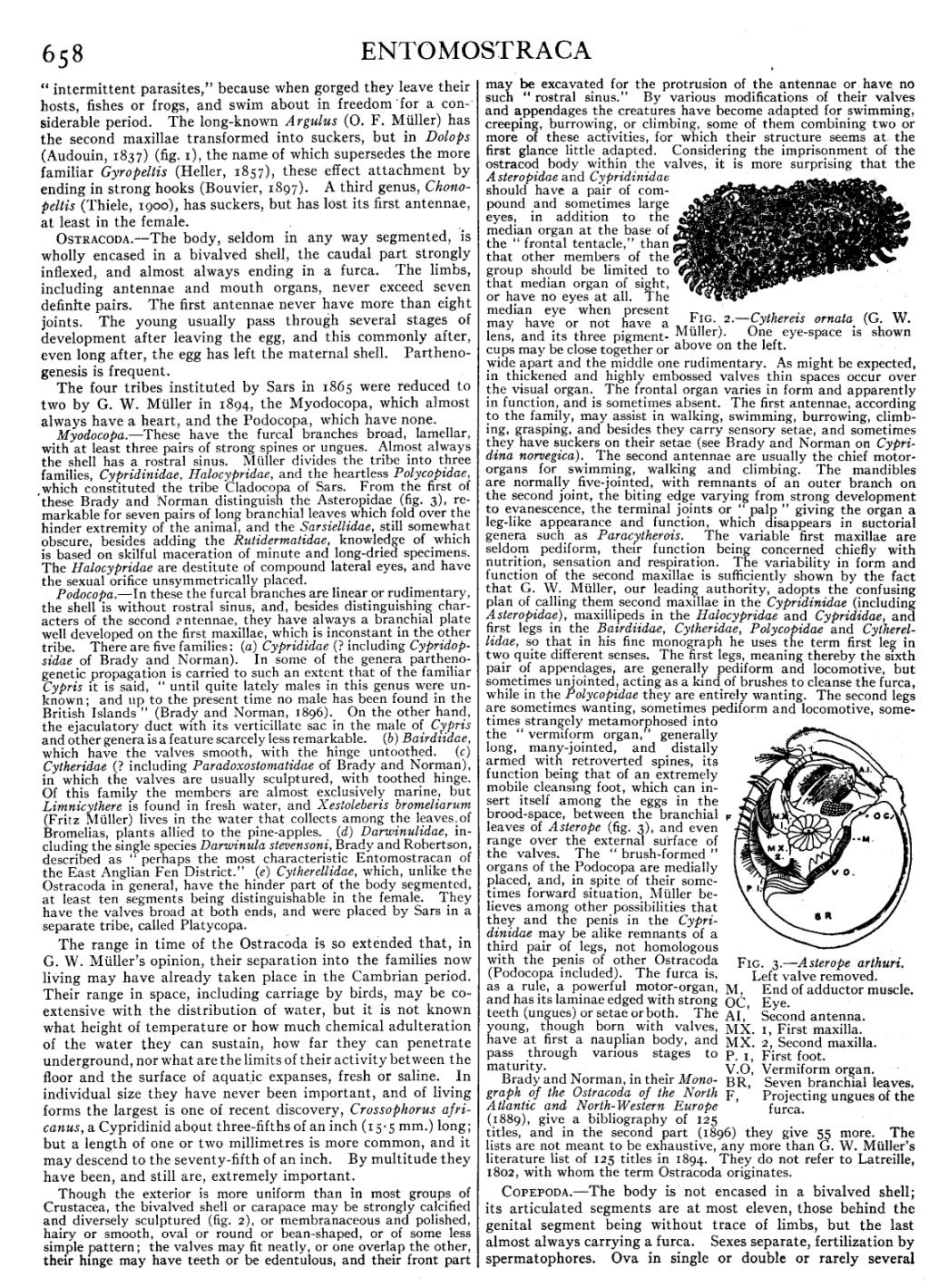

Though the exterior is more uniform than in most groups of Crustacea, the bivalved shell or carapace may be strongly calcified and diversely sculptured (fig. 2), or membranaceous and polished, hairy or smooth, oval or round or bean-shaped, or of some less simple pattern; the valves may fit neatly, or one overlap the other, their hinge may have teeth or be edentulous, and their front part may be excavated for the protrusion of the antennae or have no such “rostral sinus.” By various modifications of their valves and appendages the creatures have become adapted for swimming, creeping, burrowing, or climbing, some of them combining two or more of these activities, for which their structure seems at the first glance little adapted. Considering the imprisonment of the ostracod body within the valves, it is more surprising that the Asteropidae and Cypridinidae should have a pair of compound and sometimes large eyes, in addition to the median organ at the base of the “frontal tentacle,” than that other members of the group should be limited to that median organ of sight, or have no eyes at all. The median eye when present may have or not have a lens, and its three pigment-cups may be close together or wide apart and the middle one rudimentary. As might be expected, in thickened and highly embossed valves thin spaces occur over the visual organ. The frontal organ varies in form and apparently in function, and is sometimes absent. The first antennae, according to the family, may assist in walking, swimming, burrowing, climbing, grasping, and besides they carry sensory setae, and sometimes they have suckers on their setae (see Brady and Norman on Cypridina norvegica). The second antennae are usually the chief motor-organs for swimming, walking and climbing. The mandibles are normally five-jointed, with remnants of an outer branch on the second joint, the biting edge varying from strong development to evanescence, the terminal joints or “palp” giving the organ a leg-like appearance and function, which disappears in suctorial genera such as Paracytherois. The variable first maxillae are seldom pediform, their function being concerned chiefly with nutrition, sensation and respiration. The variability in form and function of the second maxillae is sufficiently shown by the fact that G. W. Müller, our leading authority, adopts the confusing plan of calling them second maxillae in the Cypridinidae (including Asteropidae), maxillipeds in the Halocypridae and Cyprididae, and first legs in the Bairdiidae, Cytheridae, Polycopidae and Cytherellidae, so that in his fine monograph he uses the term first leg in two quite different senses. The first legs, meaning thereby the sixth pair of appendages, are generally pediform and locomotive, but sometimes unjointed, acting as a kind of brushes to cleanse the furca, while in the Polycopidae they are entirely wanting. The second legs are sometimes wanting, sometimes pediform and locomotive, sometimes strangely metamorphosed into the “vermiform organ,” generally long, many-jointed, and distally armed with retroverted spines, its function being that of an extremely mobile cleansing foot, which can insert itself among the eggs in the brood-space, between the branchial leaves of Asterope (fig. 3), and even range over the external surface of the valves. The “brush-formed” organs of the Podocopa are medially placed, and, in spite of their sometimes forward situation, Müller believes among other possibilities that they and the penis in the Cypridinidae may be alike remnants of a third pair of legs, not homologous with the penis of other Ostracoda (Podocopa included). The furca is, as a rule, a powerful motor-organ, and has its laminae edged with strong teeth (ungues) or setae or both. The young, though born with valves, have at first a nauplian body, and pass through various stages to maturity.

Brady and Norman, in their Monograph of the Ostracoda of the North Atlantic and North-Western Europe (1889), give a bibliography of 125 titles, and in the second part (1896) they give 55 more. The lists are not meant to be exhaustive, any more than G. W. Müller’s literature list of 125 titles in 1894. They do not refer to Latreille, 1802, with whom the term Ostracoda originates.

Copepoda.—The body is not encased in a bivalved shell; its articulated segments are at most eleven, those behind the genital segment being without trace of limbs, but the last almost always carrying a furca. Sexes separate, fertilization by spermatophores. Ova in single or double or rarely several