through the library of Assur-bani-pal. Erech enjoyed much distinction in the later times, as a seat of learning and of the worship of Ishtar, and Assur-bani-pal drew largely on its literary stores for his library at Nineveh, from which we derive our principal information concerning ancient Babylonian literature. The inscriptions found here show that it continued in existence through the Persian and Seleucid periods. The ruins of the ancient site, known as Warka, which are among the largest in all Babylonia, forming an irregular circle nearly 6 m. in circumference, bounded by a wall, still standing in some places to the height of 40 ft., were explored and partially excavated by W. K. Loftus in 1850 and 1854. The most conspicuous ruin, now called Abu-Berdi, “Father of Marsh Grass,” or Buwariye, “reed matting,” because of the layers of reeds between each twelve courses of unbaked brick, is the ziggurat (tower) of the ancient temple of E-Anna. It is about 100 ft. in height, and strikingly resembles in general appearance the ruins of the ziggurat of the temple of Enlil at Nippur. Second to this in size was the ruin called Wuswas, a walled quadrangle, including an area of more than seven and a half acres, within which was an edifice 246 ft. long and 174 ft. wide, elevated on an artificial platform 50 ft. in height. The south-west façade, still standing in some places to the height of 23 ft., exhibited an interesting use of half columns, and stepped recesses for purposes of decoration. In another ruin Loftus found a wall, 30 ft. long, composed entirely of small yellow terra-cotta nail-headed cones, such as have been discovered in great numbers, inscribed and uninscribed, used for votive purposes in connexion with walls at Tello and elsewhere in Babylonia. His excavations being superficial, the Babylonian inscriptions found by him, about one hundred in all, exclusive of the ancient Ur-Gur bricks from the temple, belong in general to the neo-Babylonian, Persian and Seleucid periods. The older remains are buried deep beneath the huge mass of later debris. Loftus also discovered at Erech, almost everywhere within and without the walls, great numbers of clay coffins, piled one above another, to the height of over 30 ft., forming a vast and, on the whole, well-ordered cemetery belonging to the Persian, Parthian and later occupations of Babylonia, during which period Erech, like other cities of the south, evidently became a necropolis for a large extent of country. After Loftus’s time the mounds were visited by various travellers, but no further excavations have been conducted. Work on this important part of the site is attended with very great difficulties, owing to the inaccessible position of the ruins, the unsettled character of the country, the frequent sand-storms, and above all, the immense mass of material of later periods which must be removed before a systematic excavation of the more ancient and interesting ruins could be undertaken. A curious feature of the Warka neighbourhood is the existence of conical sand-hills, rising to a considerable height, so compact as to be almost like stone. These hills extend from Warka northward as far as Tel Ede.

See W. K. Loftus, Chaldaea and Susiana (1857); J. P. Peters, Nippur (1897); E. Sachau, Am Euphrat und Tigris (1900). Cf. also Nippur and authorities there quoted. (J. P. Pe.)

ERECHTHEUM, a temple (commonly called after Erechtheus,

to whom a portion of it was dedicated) on the acropolis at

Athens, unique in plan, and in its execution the most refined

example of the Ionic order. There is no clear evidence as to

when the building was begun, some placing it among the temples

projected by Pericles, others assigning it to the time after the

peace of Nicias in 421 B.C. The work was interrupted by the

stress of the Peloponnesian War, but in 409 B.C. a commission

was appointed to make a report on the state of the building and

to undertake its completion, which was carried out in the following

year.

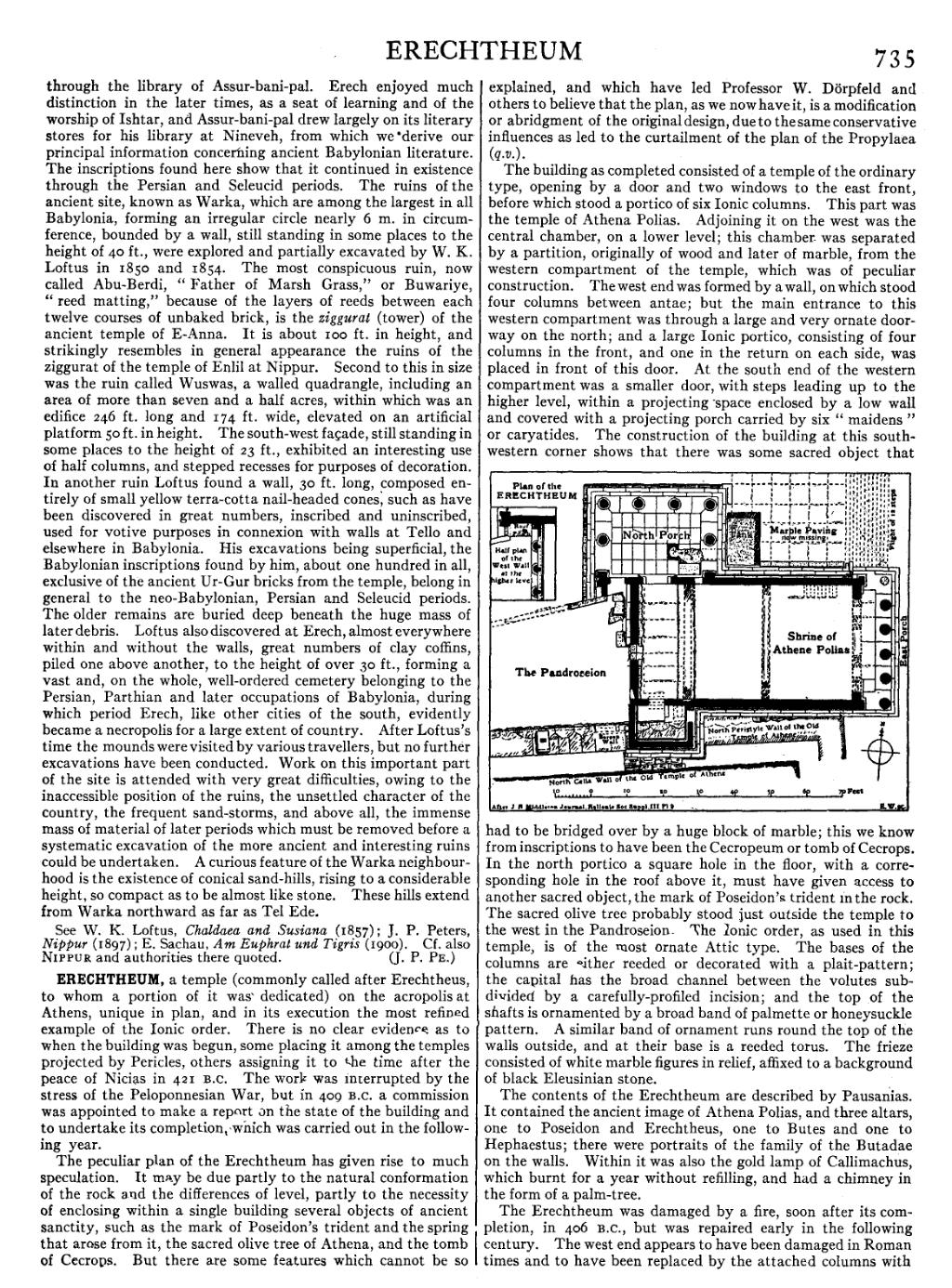

The peculiar plan of the Erechtheum has given rise to much speculation. It may be due partly to the natural conformation of the rock and the differences of level, partly to the necessity of enclosing within a single building several objects of ancient sanctity, such as the mark of Poseidon’s trident and the spring that arose from it, the sacred olive tree of Athena, and the tomb of Cecrops. But there are some features which cannot be so explained, and which have led Professor W. Dörpfeld and others to believe that the plan, as we now have it, is a modification or abridgment of the original design, due to the same conservative influences as led to the curtailment of the plan of the Propylaea (q.v.).

The building as completed consisted of a temple of the ordinary type, opening by a door and two windows to the east front, before which stood a portico of six Ionic columns. This part was the temple of Athena Polias. Adjoining it on the west was the central chamber, on a lower level; this chamber was separated by a partition, originally of wood and later of marble, from the western compartment of the temple, which was of peculiar construction. The west end was formed by a wall, on which stood four columns between antae; but the main entrance to this western compartment was through a large and very ornate doorway on the north; and a large Ionic portico, consisting of four columns in the front, and one in the return on each side, was placed in front of this door. At the south end of the western compartment was a smaller door, with steps leading up to the higher level, within a projecting space enclosed by a low wall and covered with a projecting porch carried by six “maidens” or caryatides. The construction of the building at this south-western corner shows that there was some sacred object that had to be bridged over by a huge block of marble; this we know from inscriptions to have been the Cecropeum or tomb of Cecrops. In the north portico a square hole in the floor, with a corresponding hole in the roof above it, must have given access to another sacred object, the mark of Poseidon’s trident in the rock. The sacred olive tree probably stood just outside the temple to the west in the Pandroseion. The Ionic order, as used in this temple, is of the most ornate Attic type. The bases of the columns are either reeded or decorated with a plait-pattern; the capital has the broad channel between the volutes subdivided by a carefully-profiled incision; and the top of the shafts is ornamented by a broad band of palmette or honeysuckle pattern. A similar band of ornament runs round the top of the walls outside, and at their base is a reeded torus. The frieze consisted of white marble figures in relief, affixed to a background of black Eleusinian stone.

The contents of the Erechtheum are described by Pausanias. It contained the ancient image of Athena Polias, and three altars, one to Poseidon and Erechtheus, one to Butes and one to Hephaestus; there were portraits of the family of the Butadae on the walls. Within it was also the gold lamp of Callimachus, which burnt for a year without refilling, and had a chimney in the form of a palm-tree.

The Erechtheum was damaged by a fire, soon after its completion, in 406 B.C., but was repaired early in the following century. The west end appears to have been damaged in Roman times and to have been replaced by the attached columns with