FIORENZUOLA D’ARDA, a town of Emilia, Italy, in the province of Piacenza, from which it is 14 m. S.E. by rail, 270 ft. above sea-level. Pop. (1901) 7792. It is traversed by the Via Aemilia, and has a picturesque piazza with an old tower in the centre. The Palazzo Grossi also is a fine building. Alseno lies 4 m. to the S.E., and near it is the Cistercian abbey of Chiaravalle della Colomba, with a fine Gothic church and a large and beautiful cloister (in brick and Verona marble), of the 12th-14th century.

FIORILLO, JOHANN DOMINICUS (1748–1821), German

painter and historian of art, was born at Hamburg on the 13th

of October 1748. He received his first instructions in art at an

academy of painting at Bayreuth; and in 1761, to continue

his studies, he went first to Rome, and next to Bologna, where

he distinguished himself sufficiently to attain in 1769 admission

to the academy. Returning soon after to Germany, he obtained

the appointment of historical painter to the court of Brunswick.

In 1781 he removed to Göttingen, occupied himself as a drawing-master,

and was named in 1784 keeper of the collection of prints

at the university library. He was appointed professor extraordinary

in the philosophical faculty in 1799, and ordinary

professor in 1813. During this period he had made himself

known as a writer by the publication of his Geschichte der zeichnenden

Künste, in 5 vols. (1798–1808). This was followed in

1815 to 1820 by the Geschichte der zeichnenden Künste in Deutschland

und den vereinigten Niederlanden, in 4 vols. These works,

though not attaining to any high mark of literary excellence,

are esteemed for the information collected in them, especially

on the subject of art in the later middle ages. Fiorillo practised

his art almost till his death, but has left no memorable masterpiece.

The most noticeable of his painting is perhaps the

“Surrender of Briseis.” He died at Göttingen on the 10th of

September 1821.

FIR, the Scandinavian name originally given to the Scotch

pine (Pinus sylvestris), but at present not infrequently employed

as a general term for the whole of the true conifers (Abielineae);

in a more exact sense, it has been transferred to the “spruce”

and “silver firs,” the genera Picea and Abies of most modern

botanists.

The firs are distinguished from the pines and larches by having their needle-like leaves placed singly on the shoots, instead of growing in clusters from a sheath on a dwarf branch. Their cones are composed of thin, rounded, closely imbricated scales, each with a more or less conspicuous bract springing from the base. The trees have usually a straight trunk, and a tendency to a conical or pyramidal growth, throwing out each year a more or less regular whorl of branches from the foot of the leading shoot, while the buds of the lateral boughs extend horizontally.

In the spruce firs (Picea), the cones are pendent when mature and their scales persistent; the leaves are arranged all round the shoots, though the lower ones are sometimes directed laterally. In the genus Abies, the silver firs, the cones are erect, and their scales drop off when the seed ripens; the leaves spread in distinct rows on each side of the shoot.

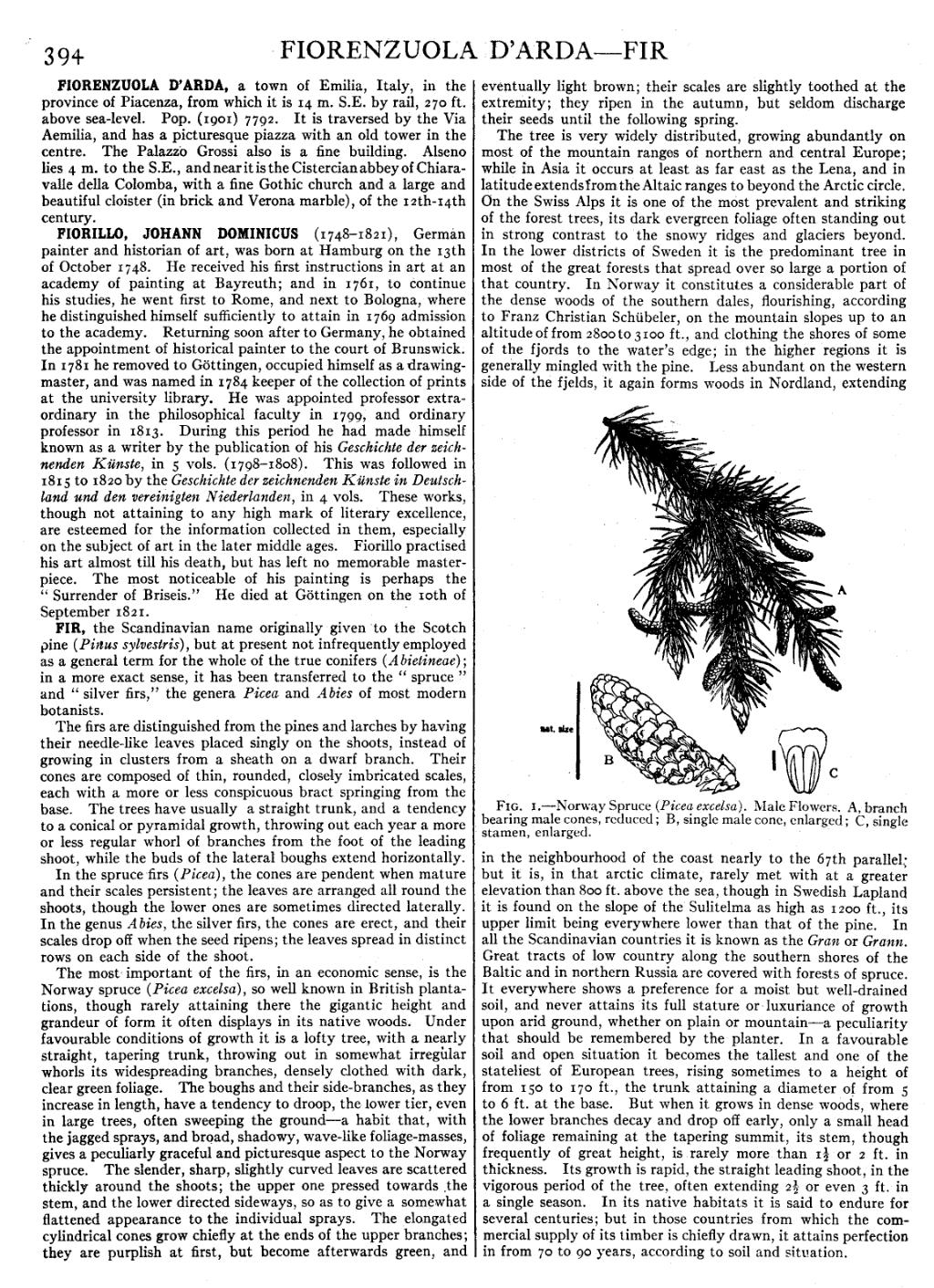

The most important of the firs, in an economic sense, is the Norway spruce (Picea excelsa), so well known in British plantations, though rarely attaining there the gigantic height and grandeur of form it often displays in its native woods. Under favourable conditions of growth it is a lofty tree, with a nearly straight, tapering trunk, throwing out in somewhat irregular whorls its widespreading branches, densely clothed with dark, clear green foliage. The boughs and their side-branches, as they increase in length, have a tendency to droop, the lower tier, even in large trees, often sweeping the ground—a habit that, with the jagged sprays, and broad, shadowy, wave-like foliage-masses, gives a peculiarly graceful and picturesque aspect to the Norway spruce. The slender, sharp, slightly curved leaves are scattered thickly around the shoots; the upper one pressed towards the stem, and the lower directed sideways, so as to give a somewhat flattened appearance to the individual sprays. The elongated cylindrical cones grow chiefly at the ends of the upper branches; they are purplish at first, but become afterwards green, and eventually light brown; their scales are slightly toothed at the extremity; they ripen in the autumn, but seldom discharge their seeds until the following spring.

|

| Fig. 1.—Norway Spruce (Picea excelsa). Male Flowers. A, branch bearing male cones, reduced; B, single male cone, enlarged; C, single stamen, enlarged. |

The tree is very widely distributed, growing abundantly on most of the mountain ranges of northern and central Europe; while in Asia it occurs at least as far east as the Lena, and in latitude extends from the Altaic ranges to beyond the Arctic circle. On the Swiss Alps it is one of the most prevalent and striking of the forest trees, its dark evergreen foliage often standing out in strong contrast to the snowy ridges and glaciers beyond. In the lower districts of Sweden it is the predominant tree in most of the great forests that spread over so large a portion of that country. In Norway it constitutes a considerable part of the dense woods of the southern dales, flourishing, according to Franz Christian Schübeler, on the mountain slopes up to an altitude of from 2800 to 3100 ft., and clothing the shores of some of the fjords to the water’s edge; in the higher regions it is generally mingled with the pine. Less abundant on the western side of the fjelds, it again forms woods in Nordland, extending in the neighbourhood of the coast nearly to the 67th parallel; but it is, in that arctic climate, rarely met with at a greater elevation than 800 ft. above the sea, though in Swedish Lapland it is found on the slope of the Sulitelma as high as 1200 ft., its upper limit being everywhere lower than that of the pine. In all the Scandinavian countries it is known as the Gran or Grann. Great tracts of low country along the southern shores of the Baltic and in northern Russia are covered with forests of spruce. It everywhere shows a preference for a moist but well-drained soil, and never attains its full stature or luxuriance of growth upon arid ground, whether on plain or mountain—a peculiarity that should be remembered by the planter. In a favourable soil and open situation it becomes the tallest and one of the stateliest of European trees, rising sometimes to a height of from 150 to 170 ft., the trunk attaining a diameter of from 5 to 6 ft. at the base. But when it grows in dense woods, where the lower branches decay and drop off early, only a small head of foliage remaining at the tapering summit, its stem, though frequently of great height, is rarely more than 112 or 2 ft. in thickness. Its growth is rapid, the straight leading shoot, in the vigorous period of the tree, often extending 212 or even 3 ft. in a single season. In its native habitats it is said to endure for several centuries; but in those countries from which the commercial supply of its timber is chiefly drawn, it attains perfection in from 70 to 90 years, according to soil and situation.