FLACOURT, ÉTIENNE DE (1607–1660), French governor of Madagascar, was born at Orleans in 1607. He was named governor of Madagascar by the French East India Company in 1648. Flacourt restored order among the French soldiers, who had mutinied, but in his dealings with the natives he was less successful, and their intrigues and attacks kept him in continual harassment during all his term of office. In 1655 he returned to France. Not long after he was appointed director general of the company; but having again returned to Madagascar, he was drowned on his voyage home on the 10th of June 1660. He is the author of a Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar (1st edition 1658, 2nd edition 1661).

See A. Malotet, Ét. de Flacourt, ou les origines de la colonisation française à Madagascar (1648–1661), (Paris, 1898).

FLAG (or “Flagge,” a common Teutonic word in this sense,

but apparently first recorded in English), a piece of bunting

or similar material, admitting of various shapes and colours,

and waved in the wind from a staff or cord for use in display

as a standard, ensign or signal. The word may simply be derived

onomatopoeically, or transferred from the botanical “flag”;

or an original meaning of “a piece of cloth” may be connected

with the 12th-century English “flage,” meaning a baby’s garment;

the verb “to flag,” i.e. droop, may have originated in the idea

of a pendulous piece of bunting, or may be connected with the

O. Fr. flaguir, to become flaccid. It is probable that almost as

soon as men began to collect together for common purposes

some kind of conspicuous object was used, as the symbol of the

common sentiment, for the rallying point of the common force.

In military expeditions, where any degree of organization and

discipline prevailed, objects of such a kind would be necessary

to mark out the lines and stations of encampment, and to keep

in order the different bands when marching or in battle. In

addition, it cannot be doubted that flags or their equivalents

have often served, by reminding men of past resolves, past deeds

and past heroes, to arouse to enthusiasm those sentiments of

esprit de corps, of family pride and honour, of personal devotion,

patriotism or religion, upon which, as well as upon good leadership,

discipline and numerical force, success in warfare depends.

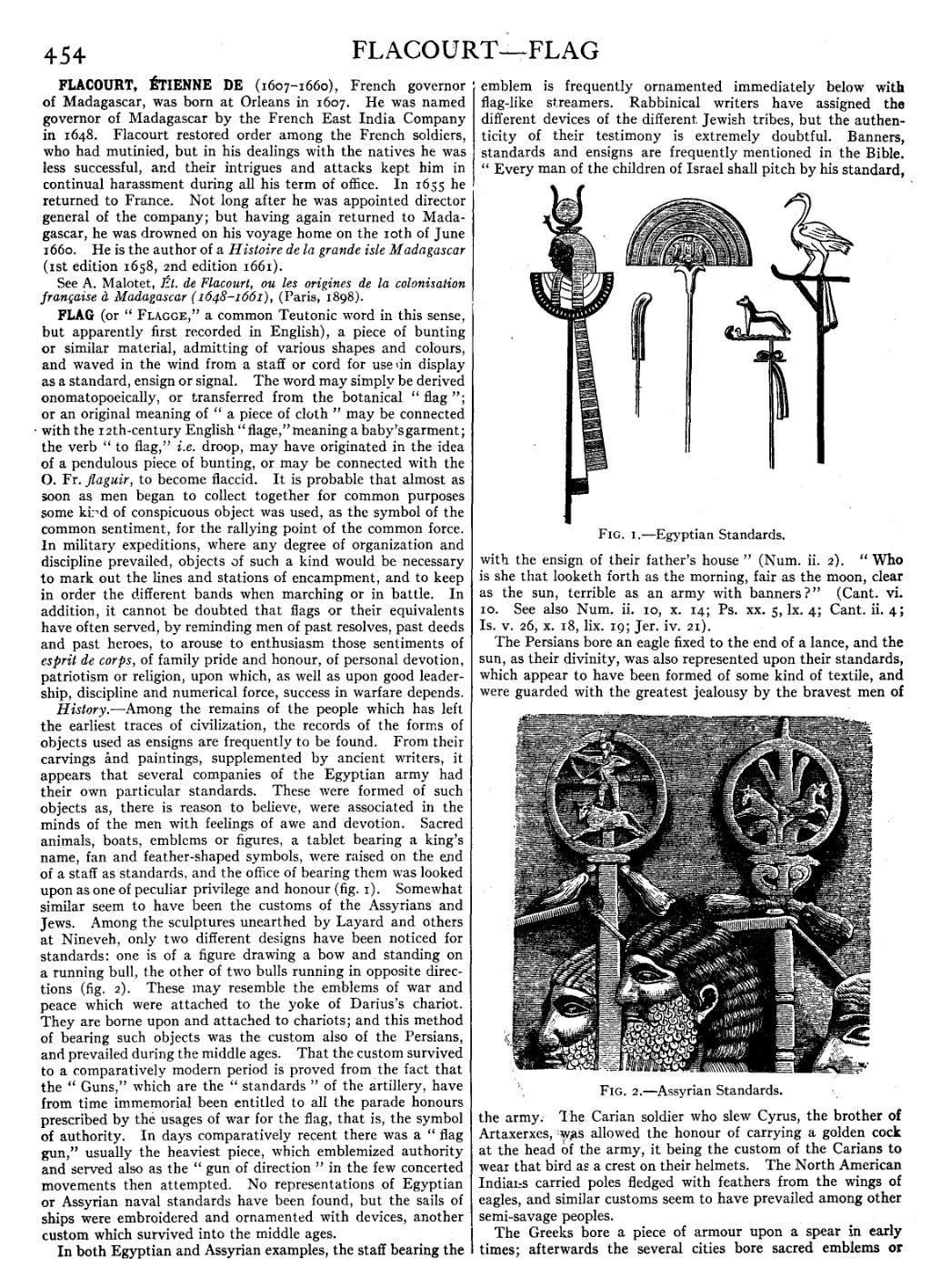

History.—Among the remains of the people which has left the earliest traces of civilization, the records of the forms of objects used as ensigns are frequently to be found. From their carvings and paintings, supplemented by ancient writers, it appears that several companies of the Egyptian army had their own particular standards. These were formed of such objects as, there is reason to believe, were associated in the minds of the men with feelings of awe and devotion. Sacred animals, boats, emblems or figures, a tablet bearing a king’s name, fan and feather-shaped symbols, were raised on the end of a staff as standards, and the office of bearing them was looked upon as one of peculiar privilege and honour (Fig. 1). Somewhat similar seem to have been the customs of the Assyrians and Jews. Among the sculptures unearthed by Layard and others at Nineveh, only two different designs have been noticed for standards: one is of a figure drawing a bow and standing on a running bull, the other of two bulls running in opposite directions (Fig. 2). These may resemble the emblems of war and peace which were attached to the yoke of Darius’s chariot. They are borne upon and attached to chariots; and this method of bearing such objects was the custom also of the Persians, and prevailed during the middle ages. That the custom survived to a comparatively modern period is proved from the fact that the “Guns,” which are the “standards” of the artillery, have from time immemorial been entitled to all the parade honours prescribed by the usages of war for the flag, that is, the symbol of authority. In days comparatively recent there was a “flag gun,” usually the heaviest piece, which emblemized authority and served also as the “gun of direction” in the few concerted movements then attempted. No representations of Egyptian or Assyrian naval standards have been found, but the sails of ships were embroidered and ornamented with devices, another custom which survived into the middle ages.

In both Egyptian and Assyrian examples, the staff bearing the emblem is frequently ornamented immediately below with flag-like streamers. Rabbinical writers have assigned the different devices of the different Jewish tribes, but the authenticity of their testimony is extremely doubtful. Banners, standards and ensigns are frequently mentioned in the Bible. “Every man of the children of Israel shall pitch by his standard, with the ensign of their father’s house” (Num. ii. 2). “Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, terrible as an army with banners?” (Cant. vi. 10. See also Num. ii. 10, x. 14; Ps. xx. 5, lx. 4; Cant. ii. 4; Is. v. 26, x. 18, lix. 19; Jer. iv. 21).

|

| Fig. 1.—Egyptian Standards. |

The Persians bore an eagle fixed to the end of a lance, and the sun, as their divinity, was also represented upon their standards, which appear to have been formed of some kind of textile, and were guarded with the greatest jealousy by the bravest men of the army. The Carian soldier who slew Cyrus, the brother of Artaxerxes, was allowed the honour of carrying a golden cock at the head of the army, it being the custom of the Carians to wear that bird as a crest on their helmets. The North American Indians carried poles fledged with feathers from the wings of eagles, and similar customs seem to have prevailed among other semi-savage peoples.

|

| Fig. 2.—Assyrian Standards. |

The Greeks bore a piece of armour upon a spear in early times; afterwards the several cities bore sacred emblems or