had already appeared in the author’s Mémoire de la génération des connaissances humaines (Berlin, 1802), which was crowned by the Academy of Berlin. In it de Gérando, after a rapid review of ancient and modern speculations on the origin of our ideas, singles out the theory of primary ideas, which he endeavours to combat under all its forms. The latter half of the work, devoted to the analysis of the intellectual faculties, is intended to show how all human knowledge is the result of experience; and reflection is assumed as the source of our ideas of substance, of unity and of identity. It is divided into two parts, the first of which is purely historical, and devoted to an exposition of various philosophical systems; in the second, which comprises fourteen chapters of the entire work, the distinctive characters and value of these systems are compared and discussed. In spite of the disadvantage that it is impossible to separate advantageously the history and critical examination of any doctrine in the arbitrary manner which de Gérando chose, the work has great merits. In correctness of detail and comprehensiveness of view it was greatly superior to every work of the same kind that had hitherto appeared in France. During the Empire and the first years of the Restoration, de Gérando found time to prepare a second edition (Paris, 1822, 4 vols.), which is enriched with so many additions that it may pass for an entirely new work. The last chapter of the part published during the author’s lifetime ends with the revival of letters and the philosophy of the 15th century. The second part, carrying the work down to the close of the 18th century, was published posthumously by his son in 4 vols. (Paris, 1847). Twenty-three chapters of this were left complete by the author in manuscript; the remaining three were supplied from other sources, chiefly printed but unpublished memoirs.

His essay Du perfectionnement moral et de l’éducation de soi-même was crowned by the French Academy in 1825. The fundamental idea of this work is that human life is in reality only a great education, of which perfection is the aim.

Besides the works already mentioned, de Gérando left many others, of which we may indicate the following:—Considérations sur diverses méthodes d’observation des peuples sauvages (Paris, 1801); Éloge de Dumarsais,—discours qui a remporté le prix proposé par la seconde classe de l’Institut National (Paris, 1805); Le Visiteur de pauvre (Paris, 1820); Instituts du droit administratif (4 vols., Paris, 1830); Cours normal des instituteurs primaires ou directions relatives à l’éducation physique, morale, et intellectuelle dans les écoles primaires (Paris, 1832); De l’éducation des sourds-muets (2 vols., Paris, 1832); De la bienfaisance publique (4 vols., 1838). A detailed analysis of the Histoire comparée des systèmes will be found in the Fragments philosophiques of M. Cousin. In connexion with his psychological studies, it is interesting that in 1884 the French Anthropological Society reproduced his instructions for the observation of primitive peoples, and modern students of the beginnings of speech in children and the cases of deaf-mutes have found useful matter in his works. See also J. P. Damiron, Essai sur la philosophie en France au XIX e siècle.

GERANIACEAE, in botany, a small but very widely distributed

natural order of Dicotyledons belonging to the subclass Polypetalae,

containing about 360 species in 11 genera. It is represented

in Britain by two genera, Geranium (crane’s-bill) and

Erodium (stork’s-bill), to which belong nearly two-thirds of the

total number of species. The plants are mostly herbs, rarely

becoming shrubby, with generally simple glandular hairs on

the stem and leaves. The opposite or alternate leaves have a

pair of small stipules at the base of the stalk and a palminerved

blade. The flowers, which are generally arranged in a cymose

inflorescence, are hermaphrodite, hypogynous, and, except in

Pelargonium, regular. The parts are arranged in fives. There

are five free sepals, overlapping in the bud, and, alternating with

these, five free petals. In Pelargonium the flower is zygomorphic

with a spurred posterior sepal and the petals differing in size

or shape. In Geranium the stamens are obdiplostemonous, i.e.

an outer whorl of five opposite the petals alternates with an

inner whorl of five opposite the sepals; at the base of each of

the antisepalous stamens is a honey-gland. In Erodium the

members of the outer whorl are reduced to scale-like structures

(staminodes), and in Pelargonium from two to seven only are

fertile. There is no satisfactory explanation of this break in

the regular alternation of successive whorls; the outer whorl

of stamens arises in course of development before the inner, so

that there is no question of subsequent displacement. There

are five, or sometimes fewer, carpels, which unite to form an

ovary with as many chambers, in each of which are one or two,

rarely more, pendulous anatropous ovules, attached to the

central column in such a way that the micropyle points outwards

and the raphe is turned towards the placenta. The long beak-like

style divides at the top into a corresponding number of slender stigmas.

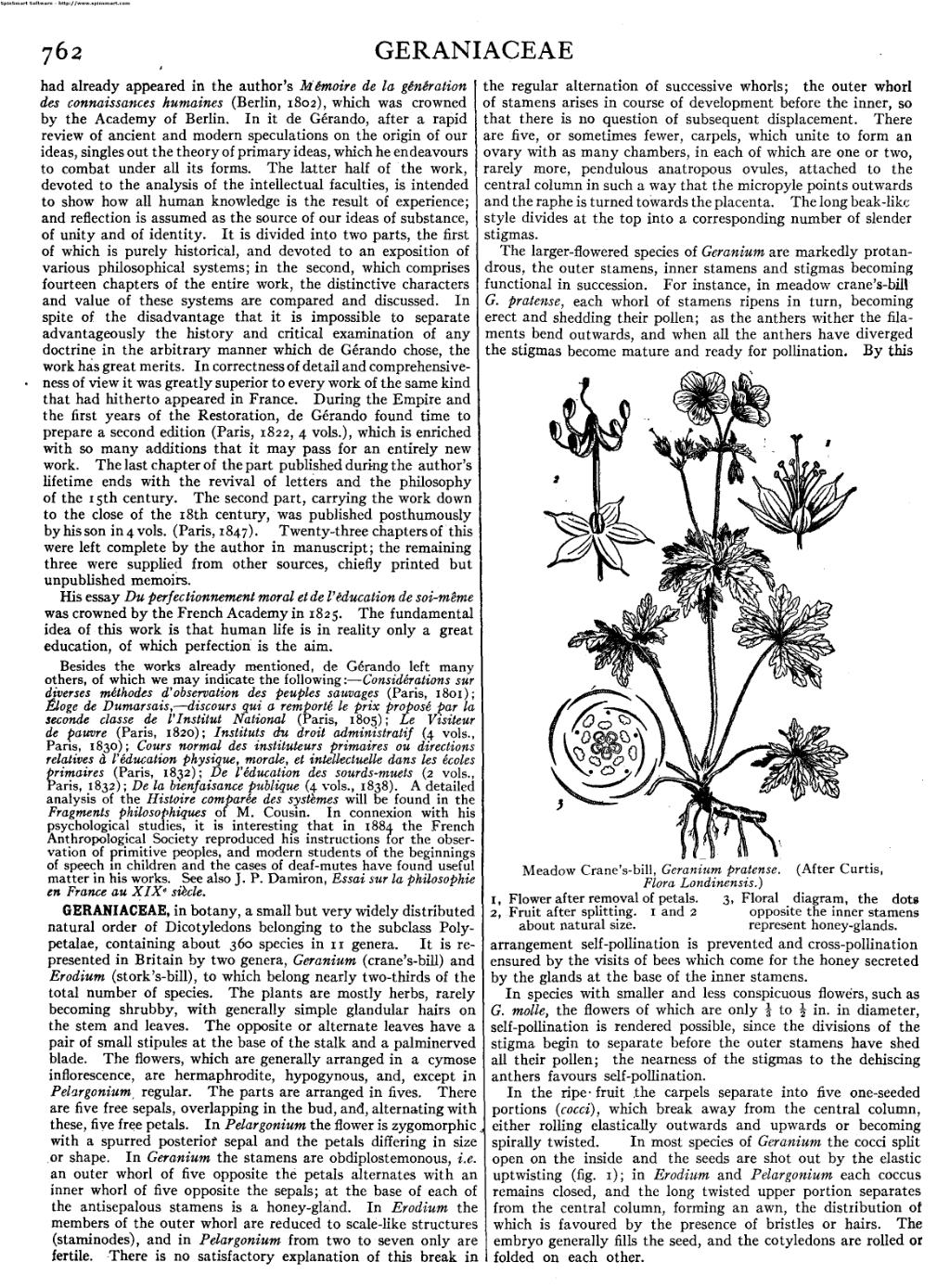

The larger-flowered species of Geranium are markedly protandrous, the outer stamens, inner stamens and stigmas becoming functional in succession. For instance, in meadow crane’s-bill G. pratense, each whorl of stamens ripens in turn, becoming erect and shedding their pollen; as the anthers wither the filaments bend outwards, and when all the anthers have diverged the stigmas become mature and ready for pollination. By this arrangement self-pollination is prevented and cross-pollination ensured by the visits of bees which come for the honey secreted by the glands at the base of the inner stamens.

In species with smaller and less conspicuous flowers, such as G. molle, the flowers of which are only 13 to 12 in. in diameter, self-pollination is rendered possible, since the divisions of the stigma begin to separate before the outer stamens have shed all their pollen; the nearness of the stigmas to the dehiscing anthers favours self-pollination.

In the ripe fruit the carpels separate into five one-seeded portions (cocci), which break away from the central column, either rolling elastically outwards and upwards or becoming spirally twisted. In most species of Geranium the cocci split open on the inside and the seeds are shot out by the elastic uptwisting (fig. 1); in Erodium and Pelargonium each coccus remains closed, and the long twisted upper portion separates from the central column, forming an awn, the distribution of which is favoured by the presence of bristles or hairs. The embryo generally fills the seed, and the cotyledons are rolled or folded on each other.